For centuries, snakes have fascinated and frightened humans in equal measure. These limbless reptiles have been portrayed as everything from cunning villains to sacred symbols across cultures worldwide. While dogs and cats are renowned for recognizing their names and responding to their owners, snakes have traditionally been viewed as more primitive creatures with limited cognitive abilities. But recent research and anecdotal evidence from snake owners suggest there might be more to these reptiles than meets the eye. The question of whether snakes can learn to recognize their names touches on deeper questions about reptilian cognition, the human-snake bond, and what it truly means for an animal to “know” its name.

Understanding Snake Cognition

Snake brains differ significantly from mammalian brains, particularly in the cerebral cortex region associated with higher learning and cognitive processing. While they lack the neocortex that mammals possess, snakes have well-developed brain structures that control their sensory processing, especially for vision and smell. Research indicates that reptiles, including snakes, possess more cognitive abilities than previously believed. Studies have shown that various reptile species can solve problems, navigate mazes, and even demonstrate social learning in some cases. Though their intelligence manifests differently from mammals, snakes possess the neural hardware necessary for certain types of learning and memory formation, which are prerequisites for name recognition.

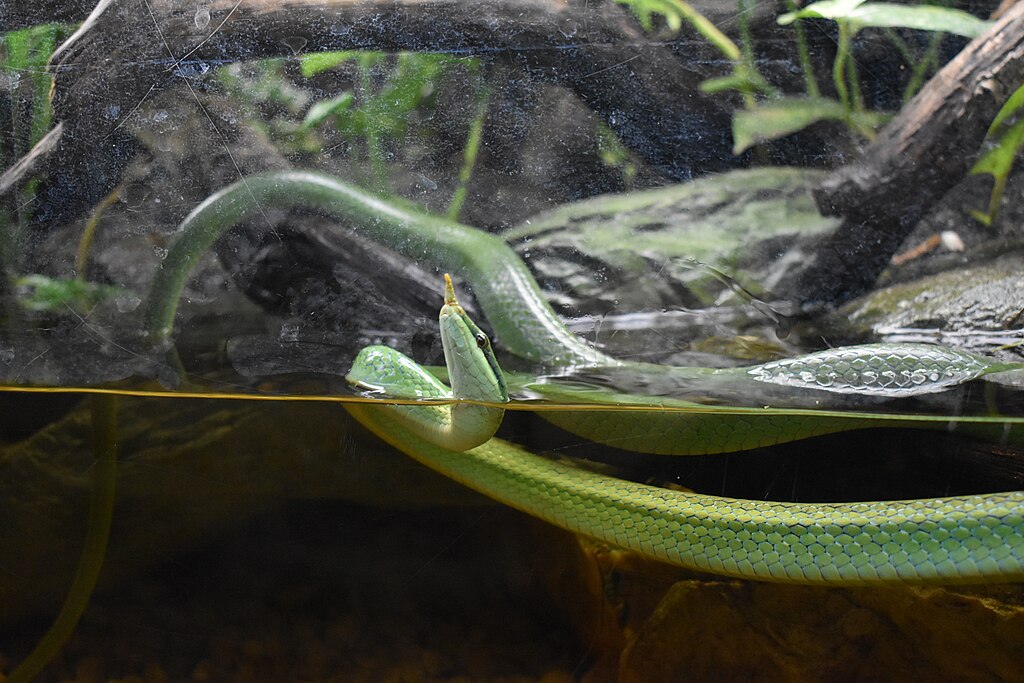

How Snakes Perceive Their World

To understand if snakes can recognize their names, we must first understand how they perceive stimuli in their environment. Unlike humans who primarily rely on vision and hearing, snakes experience the world through a complex sensory system dominated by chemical detection. Their forked tongues collect particles from the air and insert them into the Jacobson’s organ in the roof of their mouth, providing detailed chemical information about their surroundings. Many snake species have limited hearing capabilities, detecting primarily low-frequency vibrations rather than airborne sounds. Some species can detect ground vibrations through their jawbones, while others have specialized heat-sensing pits that allow them to detect prey’s body heat. This multifaceted sensory system shapes how snakes might perceive and respond to stimuli like their name being called.

Classical Conditioning in Reptiles

The mechanism through which a snake might learn to recognize its name involves a process called classical conditioning – the same learning principle famously demonstrated by Pavlov’s experiments with dogs. In this type of learning, an initially neutral stimulus (like a name) becomes associated with something meaningful to the animal (like food or handling). Studies have confirmed that reptiles, including various snake species, can be classically conditioned. For example, researchers have successfully trained snakes to associate certain visual cues with food rewards. This suggests that snakes possess the necessary neural machinery for basic associative learning, which could theoretically extend to recognizing a pattern of sounds (their name) that consistently precedes important events like feeding time.

Anecdotal Evidence from Snake Owners

Many experienced snake owners report behaviors suggesting their pets recognize their names on some level. These accounts typically describe snakes that emerge from hiding spots or become alert when their names are called, particularly around feeding time. Some owners claim their snakes respond differently to their name compared to other similar words or sounds. A ball python owner in Texas documented how her snake “Monty” would peek out from his hide when she called his name, but not when she used other similar-sounding words. While these observations aren’t scientifically controlled and may reflect anthropomorphization, the consistency of such reports across different species and owners suggests there might be something more than coincidence at play in these interactions.

Scientific Studies on Snake Learning

Formal scientific research specifically examining name recognition in snakes remains limited, but broader studies on reptilian learning provide relevant insights. Research at the University of Tennessee demonstrated that corn snakes can learn to navigate mazes and remember solutions for extended periods, indicating substantial spatial memory capabilities. Another study published in the Journal of Comparative Psychology found that timber rattlesnakes could recognize individual humans based on their scent profiles and movement patterns. Research at the University of Vienna showed that corn snakes could distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar handlers based on scent cues. While none of these studies directly addresses name recognition, they establish that snakes possess more sophisticated learning abilities than previously assumed, making name recognition at least theoretically possible.

The Role of Association in Snake Learning

If snakes do learn to recognize their names, they likely do so through consistent association rather than understanding the name as a personal identifier. When a snake owner repeatedly calls their pet’s name before feeding or handling, the snake may begin to associate that specific sound pattern with subsequent events. Over time, this association could become strong enough that the snake exhibits anticipatory behaviors when hearing its name. This differs fundamentally from how dogs or cats recognize their names, as those mammals grasp the social significance of names beyond mere association with rewards. For snakes, name recognition would represent a form of conditioned response rather than social understanding, reflecting their different evolutionary path and brain structure.

Species Differences in Learning Capacity

Not all snake species share the same cognitive capabilities, which likely impacts their potential for name recognition. Generally, active hunters like king snakes and rat snakes demonstrate more complex learning abilities than ambush predators like pythons and boas. Research suggests that species with more active hunting styles have evolved enhanced spatial memory and learning capabilities to track and pursue prey effectively. Differences in brain structure and relative brain size also exist across snake families. For example, colubrid snakes (including corn snakes and king snakes) appear to show more behavioral flexibility than some other groups. These differences suggest that some snake species may be more capable of learning to recognize their names than others, though this remains an area requiring further research.

The Importance of Consistent Training

For snake owners attempting to teach their pets to recognize their names, consistency proves absolutely critical. Successful conditioning requires repeating the same pattern of stimulus and reward many times without variation. Experts recommend calling the snake’s name immediately before positive experiences like feeding, using the exact same tone and volume each time. This training should occur in a quiet environment free from competing stimuli that might confuse the association. The process typically requires patience, as reptiles generally learn more slowly than mammals. Some snake keepers report success after months of consistent training, suggesting that name recognition is possible but requires significant dedication and a standardized approach that respects the snake’s natural learning abilities.

Distinguishing True Recognition from Other Behaviors

One challenge in determining whether snakes truly recognize their names involves distinguishing genuine recognition from other behaviors that might mimic it. Snakes are sensitive to vibrations and may respond to any voice or movement, not specifically to their name. They may also become conditioned to respond to certain tones or patterns in human speech rather than the specific name itself. Some behaviors interpreted as name recognition might actually represent the snake’s response to the owner’s scent, body heat, or subtle changes in air pressure when someone approaches their enclosure. Controlled experiments would need to eliminate these variables to conclusively demonstrate true name recognition. Such studies would require testing the snake’s response to recordings of their name versus similar-sounding words, delivered without other sensory cues that might influence behavior.

Practical Benefits of Name Training

Teaching a snake to recognize its name offers several practical benefits beyond the novelty of the accomplishment. Name recognition can serve as a useful management tool, potentially making handling sessions less stressful for both snake and keeper. Some owners report that consistent name training helps establish a more predictable routine, which contributes to the overall well-being of these animals that thrive on environmental stability. The training process itself provides valuable environmental enrichment for captive snakes, stimulating their brains and preventing the behavioral issues that can arise from lack of stimulation. Additionally, name training may serve as an early indicator of health problems, as a snake that suddenly stops responding to its name might be experiencing illness or stress that requires veterinary attention.

The Human-Snake Bond

The question of name recognition touches on the deeper emotional connection between humans and their serpentine companions. While snakes don’t form social bonds in the same way as dogs or cats, many owners report meaningful connections with their reptilian pets. Name training often represents one way that keepers attempt to bridge the evolutionary gap between humans and these ancient reptiles. For many snake enthusiasts, even the possibility that their pet recognizes their voice or responds to their presence enhances the emotional satisfaction of keeping these animals. This human-snake relationship represents a fascinating example of cross-species connection between creatures whose last common ancestor lived hundreds of millions of years ago. The quest to teach snakes their names reflects humanity’s enduring desire to communicate with and understand the non-human animals that share our world.

Ethical Considerations in Snake Training

Any attempt to train snakes raises important ethical considerations about respecting their natural behaviors and limitations. Unlike domesticated mammals that have co-evolved with humans for thousands of years, modern snakes remain essentially wild animals with instincts and behaviors shaped by millions of years of evolution as solitary hunters. Realistic expectations about what constitutes success in name training help prevent frustration for both snake and keeper. Ethical training methods must always prioritize the snake’s welfare, avoiding stress or using aversive stimuli. The most responsible approach involves working within the snake’s natural behavioral repertoire and cognitive capabilities rather than attempting to force human-like responses. This ethical framework acknowledges that while snakes may learn to recognize patterns associated with their names, their experience fundamentally differs from the social understanding demonstrated by mammals.

Future Research Directions

The question of whether snakes can learn their names points to significant gaps in our understanding of reptilian cognition that future research could address. Controlled studies using consistent methodology could help determine the extent to which different snake species can associate specific sound patterns with subsequent events. Brain imaging technologies might reveal neural activity patterns when snakes hear familiar versus unfamiliar sounds, providing objective evidence of recognition. Comparative studies across reptile species could illuminate the evolutionary development of learning capabilities in different lineages. Research into the sensory mechanisms through which snakes perceive and process auditory information would provide crucial context for understanding how they might recognize names. As scientific interest in reptile cognition continues to grow, these studies could transform our understanding of these fascinating animals and their unexpected cognitive abilities.

While definitive scientific evidence remains limited, the accumulated observations of snake owners and researchers suggest that some snakes may indeed learn to recognize their names through associative learning. This recognition likely differs fundamentally from how mammals understand names, reflecting snakes’ unique evolutionary history and sensory adaptations. Rather than viewing this as a lesser form of intelligence, we might better appreciate it as an example of how different evolutionary paths have produced diverse types of cognition across the animal kingdom. Whether through classical conditioning, association with rewards, or mechanisms not yet understood, the possibility that these ancient reptiles can learn to recognize human-given names reminds us that intelligence takes many forms in nature, and that we have much to learn about the cognitive lives of the animals that share our world.