In the remote forests of Southeast Asia dwells one of nature’s most remarkable masters of disguise—a serpent that has evolved a camouflage strategy so effective it can convince predators it’s nothing more than a patch of mold or fungus growing on the forest floor. The Vietnamese mossy frog snake (Pareatidae family) represents one of the most extraordinary examples of mimicry in the reptile world. Unlike snakes that imitate sticks, leaves, or other animals, this unique species has developed a visual appearance that resembles something most predators would never consider consuming: a patch of decaying organic matter. This remarkable evolutionary adaptation provides a fascinating glimpse into the endless ingenuity of natural selection and survival strategies in the wild.

The Remarkable Mimicry of the Mossy Frog Snake

The Vietnamese mossy frog snake has evolved one of the most unusual camouflage strategies in the reptile kingdom—mimicking patches of mold, fungus, or lichen that commonly grow on forest floors. Its skin features irregular patterns of green, brown, black, and white that precisely match the appearance of common forest fungi and molds. This remarkable resemblance extends beyond just coloration, as the snake’s scales have evolved textural modifications that create a three-dimensional effect mimicking the fuzzy or velvety appearance of actual mold growths. When motionless on the forest floor, even experienced herpetologists have been known to walk past these snakes without noticing them, mistaking them for ordinary patches of forest decomposition.

Taxonomic Classification and Related Species

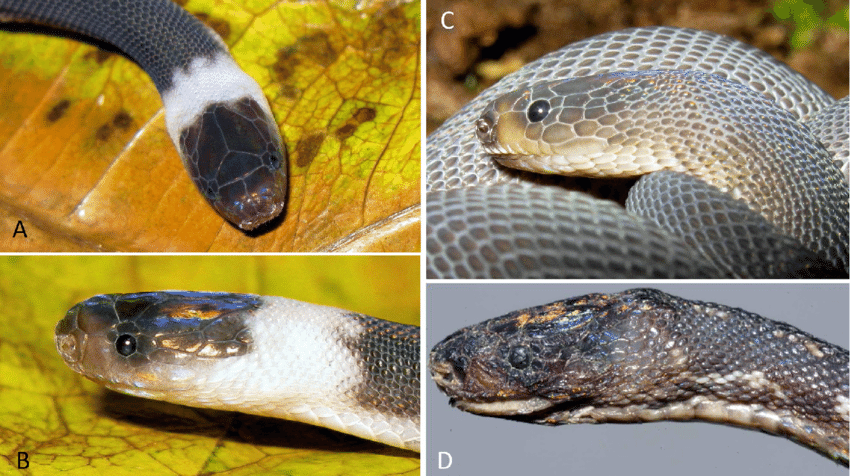

The mossy frog snake belongs to the Pareatidae family, a group of specialized slug and snail-eating snakes native to Southeast Asia. Within this family, several species show varying degrees of cryptic coloration, but the Vietnamese mossy frog snake represents the most extreme example of fungal mimicry. Closely related species include Pareas carinatus (the keeled slug-eating snake) and Pareas margaritophorus (the white-spotted slug snake), which display their own unique camouflage patterns but lack the specific mold-like appearance. Taxonomists have debated the exact classification of these specialized reptiles, with some arguing they deserve their own genus due to their unique ecological adaptations and feeding strategies compared to other colubrids.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat

These specialized reptiles inhabit the dense, humid forests of Vietnam, parts of southern China, and potentially small regions of neighboring Laos and Cambodia, though their full range remains incompletely documented. They thrive specifically in montane and submontane forests with high humidity levels between 1,000-2,000 meters elevation, where natural fungal growth is abundant on the forest floor. These snakes require very specific microhabitats with continuous moisture, dense leaf litter, and abundant mollusks to survive. Their restricted range and specific habitat requirements make them particularly vulnerable to deforestation and climate change, as they cannot adapt to drier or significantly altered environments.

Physical Characteristics Beyond Camouflage

Beyond their remarkable camouflage, mossy frog snakes possess several distinctive physical characteristics that suit their specialized lifestyle. They typically reach lengths of 30-45 centimeters, making them relatively small compared to many other snake species. Their heads are distinctly wider than their necks, with large eyes featuring vertical pupils that enhance night vision for their nocturnal hunting activities. Perhaps most remarkable are their specialized jaws and dentition, which have evolved specifically for extracting snails from their shells—they possess asymmetrical jaws with long, needle-like teeth that can reach deep into snail shells to extract the soft-bodied prey. Their body shape is somewhat flattened laterally, allowing them to move efficiently through dense leaf litter and tight spaces on the forest floor.

The Evolutionary Development of Fungal Mimicry

The evolution of fungal mimicry in these snakes represents a fascinating case of specialized adaptive camouflage that likely developed over millions of years. Scientists theorize that the adaptation began with snakes that had slightly mottled patterns providing minor camouflage advantages on forest floors rich with decomposing matter. Through natural selection, individuals with patterns and textures more closely resembling inedible fungi gained survival advantages, as predators like birds and small mammals learned to ignore what appeared to be patches of mold. This process, driven by predation pressure, eventually resulted in the remarkably accurate mimicry seen today. Genetic studies suggest this specialized camouflage developed independently from other forms of mimicry seen in related snake species, representing a unique evolutionary pathway.

Hunting and Dietary Specialization

Mossy frog snakes are highly specialized predators that feed almost exclusively on slugs and snails, a dietary restriction few other snake species share. Using chemical sensors in their forked tongues, they can detect the slime trails of gastropods across the forest floor, following these trails directly to their prey. When a snail is located, the snake employs a remarkable feeding technique—it inserts its asymmetrical jaws into the shell opening and uses specialized teeth to extract the snail’s body without breaking the shell. This feeding process can take anywhere from 15 minutes to over an hour, depending on the size of the prey and how deeply it has retreated into its shell. Their specialized diet makes them important ecological controls on mollusk populations in their forest habitats.

Behavioral Adaptations Supporting the Disguise

The mossy frog snake’s disguise isn’t solely dependent on its appearance—specific behaviors dramatically enhance its fungal mimicry. When threatened, these snakes freeze completely, often in coiled positions that further enhance their resemblance to patches of mold or fungal growth. They move extremely slowly when not alarmed, with deliberate, almost imperceptible movements that don’t break the visual illusion of being an inanimate object. Unlike many snakes that bask openly, these species seek dappled light that enhances their mottled appearance, and they often position themselves partially under leaf litter with just portions of their bodies visible, mimicking how fungi typically grow from decomposing forest material. These behavioral adaptations work in concert with their physical appearance to create one of nature’s most effective disguises.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The reproductive biology of mossy frog snakes remains one of the less-documented aspects of their natural history, though researchers have made important observations in recent years. These snakes are oviparous, laying small clutches of 4-8 elongated eggs typically hidden under rotting logs or in other moist microhabitats on the forest floor. Female snakes select nesting sites with consistent humidity levels, often choosing locations where actual fungi grow, providing both camouflage for the eggs and a future-ready environment for the hatchlings. The incubation period lasts approximately 60-75 days, with young snakes emerging already displaying the characteristic mold-like patterns, though the mimicry becomes more pronounced as they mature. Juveniles begin hunting small slugs almost immediately after hatching, requiring no parental care.

Natural Predators and Defense Mechanisms

Despite their effective camouflage, mossy frog snakes face threats from various forest predators, including birds of prey with keen vision, small mammals like civets and mongoose, and larger reptiles including monitor lizards. Their primary defense is their remarkable camouflage, which renders them nearly invisible when motionless on the forest floor. When this primary defense fails, these snakes rarely attempt to bite—instead, they release a foul-smelling musk from glands near their cloaca, which mimics the unpleasant odor of certain inedible fungi, further reinforcing their fungal disguise. If physically contacted, they may perform a distinctive defensive behavior where they roll into a loose ball with their head hidden, maintaining the appearance of a rounded fungal growth rather than a snake even when directly handled.

Conservation Status and Threats

The Vietnamese mossy frog snake faces numerous conservation challenges that threaten its specialized existence. Deforestation for agriculture, timber, and development has dramatically reduced suitable habitat throughout its range, fragmenting populations and destroying the humid microenvironments these specialists require. Climate change presents an additional threat, as rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns disrupt the consistently moist conditions needed for both the snakes and their mollusk prey. Their specialized diet compounds these problems, as they cannot simply switch food sources when mollusk populations decline. Though not currently listed as endangered, primarily due to insufficient population data, herpetologists believe these specialized reptiles are experiencing significant declines throughout their range and merit increased conservation attention.

Scientific Research Challenges

Studying mossy frog snakes presents unique challenges for researchers due to their exceptional camouflage and secretive nature. Field surveys often undercount populations since even trained herpetologists struggle to spot these masters of disguise among actual fungal growths on the forest floor. Their nocturnal habits further complicate observation, requiring specialized night survey techniques with minimal disturbance to their environment. Captive research has provided some insights, but these specialized feeders often refuse to eat in laboratory settings, making long-term studies difficult. Several research teams are now employing environmental DNA sampling of forest floors to detect the presence of these elusive reptiles without requiring visual confirmation, allowing more accurate mapping of their distribution and potential conservation needs.

Cultural Significance and Local Knowledge

Indigenous communities within the snake’s range have long recognized these unusual reptiles, incorporating them into local ecological knowledge systems. In several Vietnamese and Chinese dialects, the snake’s local name translates approximately to “forest rot snake” or “mushroom mimic,” demonstrating historical awareness of its remarkable camouflage strategy. Some traditional medicinal practices erroneously classified these snakes as poisonous due to their unusual appearance and the defensive musk they produce, though they are completely harmless to humans. Local forest guides have often proved invaluable to scientific research teams, as their lifetime of experience in the forests gives them a remarkable ability to spot these camouflage experts where others see only forest debris and fungal growth.

Similar Mimicry in Other Species

While the mossy frog snake represents perhaps the most specialized case of fungal mimicry in snakes, this evolutionary strategy appears in various forms across other species. The mossy leaf-tailed gecko of Madagascar (Uroplatus sikorae) displays a similar mimicry, with mottled patterns resembling lichens and fungi on tree bark. Certain frogs, most notably members of the Theloderma genus like the Vietnamese mossy frog, exhibit remarkably similar adaptations with bumpy skin textures and color patterns mimicking moldy surfaces. Among invertebrates, several moth species like the peppered moth (Biston betularia) and certain katydids display fungal-like patterns that help them blend with lichen-covered trees. These parallel evolutionary developments across unrelated species highlight how similar environmental pressures can drive convergent adaptations when the camouflage strategy proves particularly effective.

In the shadowy understory of Southeast Asian forests, the remarkable mossy frog snake continues its ancient masquerade, blending seamlessly with the decay and renewal of the forest floor. Its extraordinary mimicry represents one of evolution’s most specialized adaptations—a living testament to the power of natural selection to craft solutions to the eternal challenge of survival. As deforestation continues to threaten its specialized habitat, the future of this master of disguise remains uncertain. Yet in its remarkable adaptation, we find a powerful reminder of nature’s endless creativity and the countless evolutionary wonders that still await discovery in the world’s remaining wild places.