Beneath the surface of our planet, hidden from human eyes, exists a remarkable reptile that has evolved to thrive in one of Earth’s most unusual habitats – underground lakes and water systems. The olm (Proteus anguinus), often called the “human fish” or “cave salamander,” is not technically a snake but rather an aquatic salamander that bears a striking resemblance to serpentine creatures. This fascinating amphibian has adapted to life in complete darkness, developing unique physiological and behavioral traits that allow it to navigate and survive in subterranean aquatic environments. From its pale, almost translucent skin to its ability to detect electrical fields, the olm represents one of nature’s most extraordinary examples of adaptation to extreme environments. Let’s dive deeper into the mysterious world of this underground dwelling creature and explore what makes it so special in the animal kingdom.

The Olm: A Living Fossil in Underground Waters

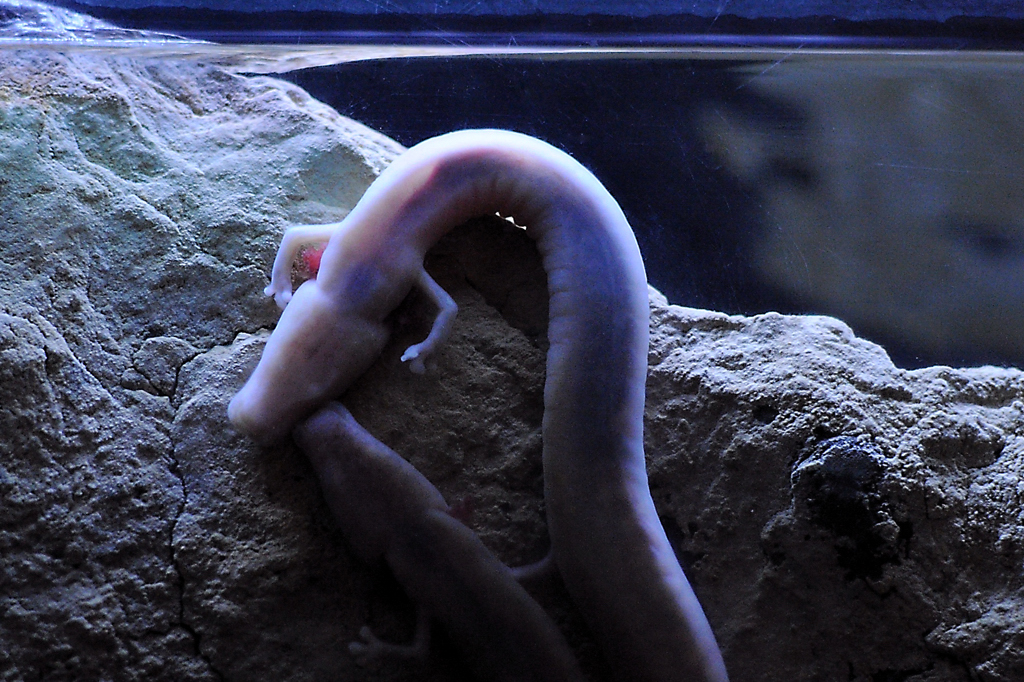

The olm (Proteus anguinus) stands as one of the most fascinating creatures adapted to subterranean aquatic life, often mistaken for a snake due to its elongated, serpentine body. This remarkable amphibian belongs to the family Proteidae and is the only member of the genus Proteus, representing a truly unique evolutionary path. Scientists consider the olm a living fossil, as it has remained virtually unchanged for over 20 million years, making it a window into ancient evolutionary history. Its closest relatives are North American mudpuppies, though the olm has developed far more specialized adaptations for its cave-dwelling lifestyle. What makes this creature particularly remarkable is its endemism to a small karst region spanning parts of Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, specifically within the underground water systems of the Dinaric Alps.

Physical Characteristics of the Cave-Dwelling Wonder

The olm possesses a slender, cylindrical body typically measuring 20-30 centimeters (8-12 inches) in length, though some specimens have reached up to 40 centimeters. Its most striking feature is its pale, almost translucent pinkish-white skin that lacks pigmentation, a common trait among cave-dwelling animals that never see sunlight. This ghostly appearance is what earned it the nickname “human fish” among locals who observed its flesh-colored skin. The olm retains its external gills throughout its life, appearing as crimson, feathery tufts on either side of its head – a phenomenon called neoteny, where larval traits persist into adulthood. Its limbs are dramatically reduced, with tiny arms and legs each ending in just three digits, contributing to its snake-like appearance despite being an amphibian. Perhaps most remarkable are its eyes, which initially develop but then regress during embryonic development, eventually becoming covered by layers of skin – a testament to the unnecessary nature of vision in its perpetually dark environment.

The Unique Habitat: Underground Lakes and Rivers

The olm’s habitat consists exclusively of water-filled cave systems within the karst landscapes of southeastern Europe, primarily in the Dinaric Alps. These subterranean environments feature complex networks of underground rivers, lakes, and aquifers formed through the dissolution of soluble rocks like limestone and dolomite. The temperature within these cave systems remains remarkably stable, typically ranging between 8-12°C (46-54°F) year-round, providing a consistent environment despite seasonal changes on the surface. Water clarity plays a crucial role in the olm’s survival, as these creatures depend on pristine conditions – their habitats feature water filtered through layers of rock, resulting in exceptional purity. The interconnected nature of these underground water systems allows olms to navigate and disperse through vast subterranean networks, though they generally prefer slow-moving or still waters with rocky bottoms where they can easily move and hunt.

Extraordinary Sensory Adaptations for Darkness

Living in perpetual darkness has driven the olm to develop sensory adaptations that compensate for the absence of visual stimuli. While its eyes are vestigial and covered by skin, the olm possesses an extraordinary sense of hearing that allows it to detect even the slightest vibrations in the water, helping it locate prey and avoid potential dangers. Perhaps most remarkable is its ability to detect electrical fields through specialized epidermal sensory receptors, enabling it to sense the presence of other organisms even without physical contact. The olm’s sense of smell is exceptionally developed, with chemoreceptors that can detect minute traces of organic compounds in the water, guiding it toward potential food sources in the nutrient-poor cave environment. Additionally, researchers have discovered that these creatures can even sense magnetic fields, potentially allowing them to orient themselves within the complex underground labyrinth of their habitat – a navigational ability that remains an active area of scientific research.

The Mysterious Life Cycle and Extreme Longevity

The olm exhibits one of the most remarkable life histories among vertebrates, with a lifespan that can exceed 100 years – an extraordinary duration for an animal of its size. Sexual maturity arrives incredibly late, typically between 12-15 years of age, representing one of the slowest maturation rates among amphibians. The reproductive cycle is equally unusual, with females laying eggs only once every six to twelve years, typically producing 35-70 eggs that are carefully attached to the undersides of submerged rocks. Development proceeds at an extraordinarily slow pace, with eggs taking up to 140 days to hatch – significantly longer than most amphibian species. Perhaps most remarkable is the olm’s metabolic efficiency; these creatures can survive without food for extraordinary periods, with documented cases of individuals living without feeding for up to a decade by reducing their activity and drawing on energy reserves, an adaptation perfectly suited to their nutrient-poor environment.

Hunting and Feeding Behaviors in Darkness

Despite its delicate appearance, the olm is an effective predator in its subterranean habitat, primarily feeding on small crustaceans, snails, and insect larvae that share its underground environment. Hunting primarily occurs through a combination of passive waiting and active searching, with the olm using its heightened non-visual senses to detect prey movement in the water. Once prey is detected, the olm approaches with slow, deliberate movements before capturing food with a surprisingly quick strike using its small but effective mouth. Digestion proceeds at an extraordinarily slow pace, consistent with the olm’s generally slow metabolism and energy conservation strategies. Interestingly, olms do not need to feed frequently – their remarkable metabolic efficiency allows them to survive on very little food, sometimes going months or even years between substantial meals when necessary, a critical adaptation to an environment where food resources can be scarce and unpredictable.

The Black Olm: A Rare Pigmented Variant

While the typical olm displays the characteristic pinkish-white coloration, a rare and fascinating subspecies known as the black olm (Proteus anguinus parkelj) was discovered in 1986 in southeastern Slovenia. This variant possesses distinct dark pigmentation, shorter limbs, and a more robust build compared to its pale relatives, representing an entirely different evolutionary path within the same genus. The black olm retains more functional eyes than its unpigmented counterpart, suggesting it may inhabit cave areas with at least some occasional exposure to light or evolved more recently from surface-dwelling ancestors. Scientists believe the black olm may represent an intermediate evolutionary stage between surface-dwelling salamanders and the fully cave-adapted white olm, providing valuable insights into the process of adaptation to subterranean environments. The discovery of this variant has opened new avenues for research into the evolutionary history and genetic diversity of these remarkable creatures, though the black olm remains exceedingly rare and is confined to an even more restricted geographical range than its more common relative.

Conservation Status and Threats

The olm faces significant conservation challenges and is currently classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to its extremely limited range and specific habitat requirements. The primary threat comes from water pollution, as agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and urban contamination can easily infiltrate the karst systems where olms live, introducing toxins into their otherwise pristine environment. Water extraction for human use has also become increasingly problematic, as it alters the flow patterns and water levels in the underground systems that olms depend upon for survival. Climate change represents an emerging threat, as alterations in precipitation patterns affect the recharge rates of subterranean water systems and could disrupt the stable temperature regimes that have remained constant for millennia. Additionally, the extremely slow reproductive rate of olms makes population recovery particularly challenging once numbers decline, as a single female may only reproduce a few times throughout her entire century-long lifespan.

Cultural Significance and Historical Beliefs

Throughout history, the olm has captured human imagination and featured prominently in European folklore, particularly in the regions where it naturally occurs. Local legends once claimed these pale, serpentine creatures were baby dragons washed up from underground lairs during heavy rains, giving rise to the Slovenian name “človeška ribica” (human fish) due to its flesh-colored skin. The scientific community first became aware of the olm in the 1689 when Baron Janez Vajkard Valvasor documented strange creatures appearing in karst springs after heavy rainfall in his book “The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola.” In the 18th century, naturalist Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti provided the first scientific description of the olm, though for many years scientists debated whether these creatures were larvae of some unknown species rather than a neotenic amphibian. Today, the olm serves as an important cultural symbol and flagship species for cave conservation efforts in Slovenia and Croatia, appearing on coins, in artwork, and as a frequent subject in regional environmental education.

Scientific Importance and Research Value

The olm represents an invaluable subject for scientific research across multiple disciplines due to its unique adaptations and evolutionary history. Medical researchers study the olm’s remarkable regenerative capabilities, as these creatures can regrow damaged limbs and tissues even at advanced ages, potentially offering insights for human regenerative medicine. Evolutionary biologists examine the olm as a model of regressive evolution, where certain features (like eyes) have been reduced while others (sensory systems) have been enhanced in response to environmental pressures. The olm’s extraordinary longevity and resistance to aging have made it a subject of interest for gerontologists seeking to understand the biological mechanisms behind extended lifespan. Additionally, ecologists use olms as indicator species for groundwater quality, as their presence generally signals pristine conditions, while their absence or decline can provide early warning of environmental degradation in underground water systems that might otherwise go undetected.

Captive Breeding and Conservation Efforts

To safeguard the future of this remarkable species, several dedicated conservation programs have been established throughout Europe, with the most notable being at Postojna Cave in Slovenia. This facility has developed specialized protocols for breeding olms in captivity, achieving significant success after decades of trial and error in replicating the specific conditions required for reproduction. In 2016, the Postojna Cave program made international headlines when a female olm successfully laid eggs that were then carefully monitored through a live stream watched by millions around the world. Beyond breeding efforts, conservation initiatives include strict protection of cave systems, monitoring of water quality in karst regions, and public education campaigns to raise awareness about these unique creatures and their fragile habitat requirements. Researchers are also exploring techniques for habitat restoration in damaged cave systems and establishing genetic repositories to preserve the DNA diversity of wild populations as insurance against potential future losses.

Discovering New Populations and Distribution

Despite centuries of study, new discoveries regarding olm distribution continue to emerge, highlighting how much remains unknown about these elusive creatures. Recent environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling techniques have allowed scientists to detect olm presence without direct observation, revealing previously unknown populations in cave systems where they had never been directly observed. In 2019, researchers confirmed olm populations in Montenegro for the first time, expanding the known range and suggesting that the distribution might be more extensive than previously documented. Each newly discovered population provides valuable genetic material and potential adaptations that could be crucial for conservation efforts and understanding the species’ evolutionary history. These findings have prompted more comprehensive mapping projects of subterranean habitats throughout the Dinaric karst region, with speleologists and biologists collaborating to document the complex underground networks that support these remarkable animals.

The Future of Underground Dwellers in a Changing World

The future of the olm remains precarious as human activities increasingly impact even the most isolated natural environments on our planet. Climate models predict significant changes in precipitation patterns across the Dinaric karst region, potentially altering the hydrological cycles that have remained stable for millennia in the olm’s underground habitat. Increasing urbanization and industrial development in regions above critical cave systems continue to pose pollution risks, despite improved environmental regulations in recent decades. However, there are reasons for cautious optimism, as public awareness and scientific interest in these unique creatures have never been higher, driving support for conservation initiatives and habitat protection. Advances in monitoring technology, including remote sensors and environmental DNA sampling, allow for non-invasive tracking of populations and early detection of potential threats. Perhaps most encouraging is the increasing recognition of underground ecosystems as vital components of biodiversity conservation, elevating the status of cave-dwelling species like the olm in environmental protection frameworks across Europe and beyond.

The olm represents one of nature’s most extraordinary evolutionary experiments – a creature perfectly adapted to life in a world without light. Through millions of years of isolation in underground lakes and rivers, it has developed sensory capabilities, metabolic adaptations, and life history strategies unlike any other vertebrate on Earth. As we continue to study these remarkable animals, they offer us not only scientific insights but also a powerful reminder of the incredible diversity of life on our planet and the importance of preserving even the most hidden ecosystems. The future of the olm and other specialized cave-dwelling creatures will depend on our ability to balance human development with protection of the unseen natural wonders beneath our feet – ensuring that these living fossils continue their remarkable journey through evolutionary time.