In the rich tapestry of nature’s adaptations, few are as ingenious as the strategy employed by the Asian mud snake (Enhydris subtaeniata). This remarkable reptile has evolved a fascinating behavior: occupying abandoned turtle shells as makeshift homes. This unique ecological niche represents one of nature’s most creative examples of habitat repurposing, where one animal’s discarded shelter becomes another’s sanctuary. The phenomenon showcases the incredible adaptability of wildlife and highlights the complex interrelationships between different species. Let’s explore this captivating example of evolutionary innovation and discover what makes this snake’s lifestyle so extraordinary.

The Identity of the Shell-Dwelling Serpent

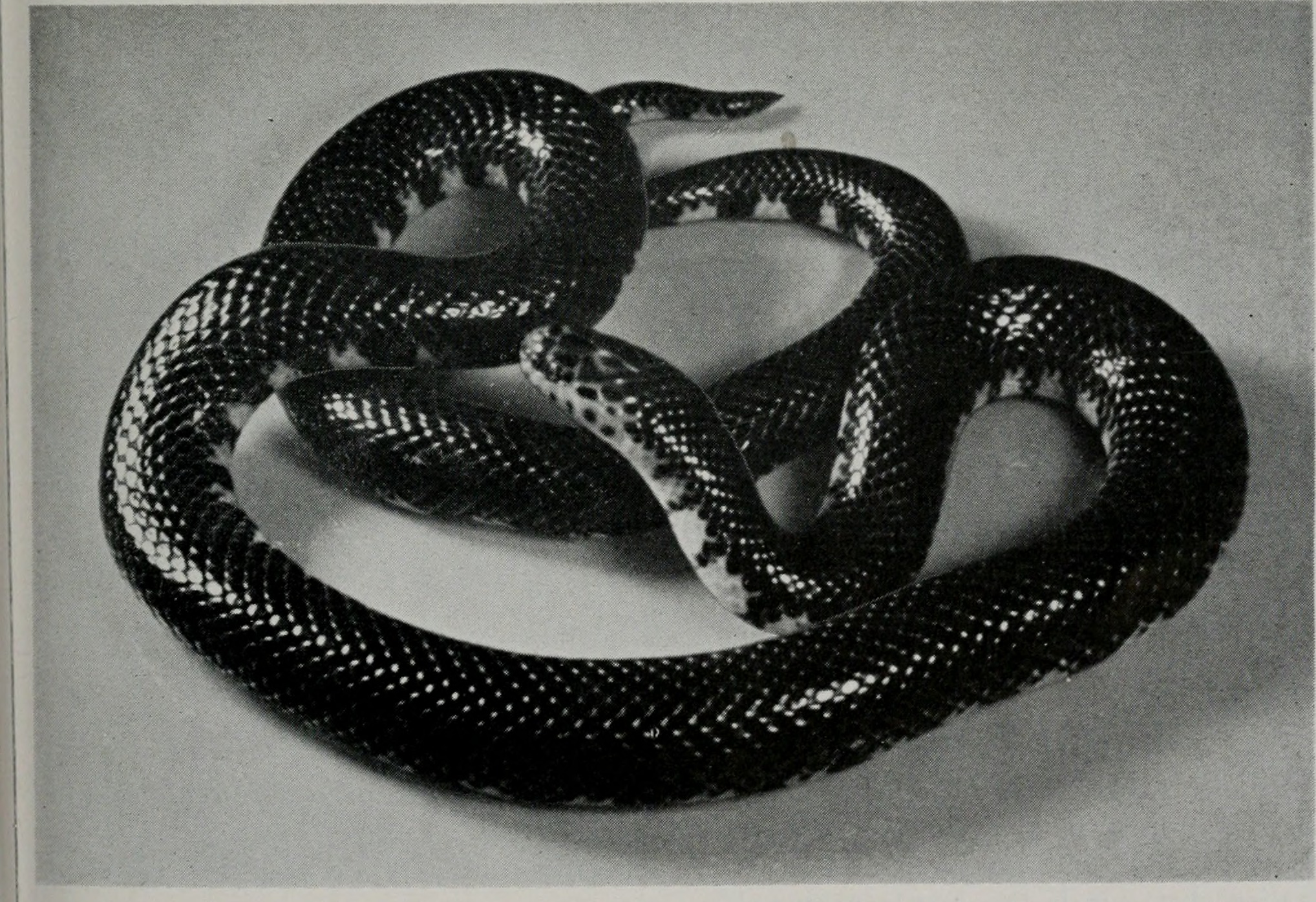

The primary snake known for inhabiting abandoned turtle shells is the Asian mud snake (Enhydris subtaeniata), a member of the Homalopsidae family native to Southeast Asia. These semi-aquatic reptiles typically grow to lengths of 50-70 centimeters and display coloration ranging from olive-brown to grayish with subtle darker stripes along their bodies. Unlike many of their cousins, these snakes possess a mild temperament and lack venom potent enough to harm humans, making them relatively harmless to people they might encounter. Their specialized adaptations for aquatic environments include valve-like nostrils and eyes positioned toward the top of their head, allowing them to remain mostly submerged while still breathing and seeing above the water’s surface.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat

Asian mud snakes inhabit wetland ecosystems throughout Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and parts of Malaysia, where they thrive in rice paddies, marshes, and slow-moving streams with muddy bottoms. These environments support both the snakes and various freshwater turtle species, creating the ecological conditions necessary for this unusual shell-dwelling behavior to emerge. The seasonal fluctuations in these regions, alternating between monsoon floods and dry periods, may contribute to the snakes’ need for adaptable shelter options throughout the year. Researchers have observed particularly high concentrations of shell-dwelling mud snakes in the Tonle Sap lake region of Cambodia, where annual flood cycles dramatically transform the landscape and may drive increased shell utilization.

The Shell Acquisition Process

The process by which these snakes come to occupy turtle shells begins with the natural cycle of a turtle’s life and death in their shared aquatic habitats. When freshwater turtles die of natural causes, predation, or human harvesting, their carapaces often remain intact and eventually sink to the bottom of their watery homes. The Asian mud snake doesn’t actively hunt or harm turtles to acquire shells but opportunistically discovers and investigates these abandoned structures. Researchers have observed that the snakes seem to prefer shells that have been naturally cleaned by decomposition and water action, typically shells that have been vacant for at least several weeks. The snake carefully inspects the shell’s opening before gradually maneuvering its flexible body into the protective confines of its new home.

Evolutionary Advantages of Shell Dwelling

Living inside abandoned turtle shells offers the Asian mud snake several significant evolutionary advantages that have helped this behavior persist. The most obvious benefit is protection from predators, as the hard shell provides a nearly impenetrable barrier against birds of prey, monitor lizards, and other threats that might otherwise target these snakes. Additionally, the shell creates a microclimate that helps the snake regulate its body temperature and maintain hydration levels, especially important during dry seasons when water sources may become limited. Research suggests that shell-dwelling individuals may experience lower predation rates compared to their shell-less counterparts, with one study indicating up to 30% higher survival rates during vulnerable periods. This survival advantage likely represents the primary selective pressure that has reinforced this unusual behavioral adaptation over evolutionary time.

Anatomical Adaptations for Shell Life

The Asian mud snake displays several anatomical features that make shell-dwelling possible, though these adaptations likely evolved primarily for aquatic life rather than specifically for shell habitation. Their remarkably flexible spine and ribs allow them to contort into the curved interior spaces of turtle shells without injury. The snake’s relatively slim body profile compared to other aquatic snakes of similar length facilitates easier entry and exit through the limited openings of the carapace. Their respiratory system has evolved to function efficiently even when the snake is partially coiled or compressed within tight spaces, enabling comfortable breathing within the confined shell environment. Interestingly, juvenile mud snakes show a greater propensity for shell occupation than adults, suggesting that smaller body size may be advantageous for maximizing the benefits of this behavior.

Hunting Behavior While Shell-Bound

Despite residing in turtle shells, these snakes maintain active hunting patterns, emerging primarily during dawn and dusk to forage for prey. Their diet consists mainly of small fish, amphibians, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates that share their wetland habitats. Asian mud snakes employ a fascinating hunting technique where they extend part of their body from the shell opening while keeping their posterior anchored safely inside, allowing them to strike at passing prey while maintaining the shell’s protection. This “anchor and ambush” strategy represents a specialized behavioral adaptation that maximizes both feeding success and safety. Research indicates that shell-dwelling snakes may actually have greater hunting success rates than their free-roaming counterparts, as prey animals may not recognize the partially concealed predator until it’s too late.

Reproduction and Shell Utilization

The reproductive behavior of shell-dwelling mud snakes reveals fascinating intersections between their unusual habitat choice and life cycle. Female Asian mud snakes sometimes utilize larger turtle shells as protected nursery sites where they can give birth safely hidden from potential threats. Unlike many snake species that lay eggs, these mud snakes are ovoviviparous, meaning they give birth to live young after carrying eggs internally, typically producing 5-12 offspring per breeding cycle. Newborn snakes often remain near their mother’s shell for several days before dispersing to find smaller shells or other hiding places. Researchers have documented cases where multiple juvenile snakes temporarily share a single larger shell during their vulnerable early days, creating a kind of communal nursery arrangement that’s unusual among typically solitary reptiles.

Seasonal Patterns of Shell Occupation

Shell-dwelling behavior among Asian mud snakes follows distinct seasonal patterns that reflect changing environmental conditions throughout the year. During monsoon seasons when waters rise and currents strengthen, these snakes show increased rates of shell occupation, likely seeking stable anchoring against being swept away by flood waters. Conversely, in dry seasons, shells provide crucial humid microenvironments that help prevent dehydration as surrounding waters recede and temperatures rise. Long-term observational studies have revealed that individual snakes may use the same shell repeatedly over multiple seasons if it remains available, suggesting they develop site fidelity to particular shells. This seasonal variation in shell utilization rates provides important insights into how environmental pressures shape and reinforce this unusual behavioral adaptation.

Ecological Relationships with Turtles

The relationship between Asian mud snakes and the turtles whose shells they eventually inhabit represents a fascinating ecological connection that doesn’t fit neatly into standard categories of species interactions. Since the snakes only occupy shells after the turtle has died, this isn’t a typical predator-prey relationship, nor is it parasitic or commensalistic in the traditional sense. Ecologists classify this interaction as sequential habitat utilization or “habitat succession,” where one species makes use of structural resources left behind by another. Interestingly, some turtle species whose shells are commonly inhabited include the Asian leaf turtle (Cyclemys dentata) and various mud turtles from the Kinosternidae family, creating an ecological link between these otherwise unrelated reptiles. The snake’s use of turtle shells represents an elegant example of how evolution can produce unexpected connections between different branches of the tree of life.

Threats to Shell-Dwelling Snake Populations

Despite their innovative adaptation, shell-dwelling mud snakes face significant threats in the modern world, many stemming from human activities that disrupt their specialized ecological niche. Wetland drainage for agricultural and urban development has destroyed vast areas of suitable habitat throughout Southeast Asia, reducing both snake and turtle populations. Commercial turtle harvesting for food and traditional medicine has dramatically decreased the availability of shells in many regions, with some local turtle populations declining by more than 90% in recent decades. Water pollution from agricultural runoff, industrial discharge, and plastic waste degrades the aquatic environments these snakes depend on, affecting both their health and that of their prey species. Conservation biologists have identified these snakes as important bioindicators of wetland ecosystem health, making their population trends valuable metrics for environmental monitoring efforts.

Scientific Research Challenges

Studying shell-dwelling snakes presents unique challenges for herpetologists and wildlife researchers attempting to document this behavior. The semi-aquatic nature of mud snakes makes direct observation difficult, often requiring specialized underwater photography equipment or careful extraction methods that don’t harm the animals. Distinguishing opportunistic shell use from consistent behavioral patterns requires long-term monitoring of multiple individuals, a logistically challenging prospect in remote wetland environments. Ethical considerations also complicate research efforts, as scientists must balance the need for data collection with minimizing disturbance to these sensitive reptiles. Recent advances in miniaturized tracking technology and environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling are opening new avenues for less invasive study methods that may yield more comprehensive insights into this fascinating ecological phenomenon.

Cultural Significance and Folklore

The shell-dwelling behavior of Asian mud snakes has not gone unnoticed in the cultural traditions of communities that share their habitat. In several rural Thai and Cambodian communities, these snakes feature in local folklore as symbols of resourcefulness and adaptation, sometimes appearing in cautionary tales about making the best of difficult circumstances. Some traditional belief systems in the region hold that finding a snake living in a turtle shell brings good fortune to fishermen, supposedly indicating abundant aquatic life in the area. Indigenous ecological knowledge often includes detailed observations about these snakes that have proven valuable to scientific researchers, highlighting the importance of integrating traditional wisdom with modern conservation efforts. The cultural significance attached to these creatures sometimes provides an added layer of local protection that complements formal conservation initiatives.

Conservation Efforts and Future Prospects

Conservation initiatives focused on preserving wetland ecosystems throughout Southeast Asia indirectly benefit shell-dwelling mud snakes by protecting their specialized habitat. Several regional organizations have established turtle breeding and release programs aimed at restoring declining populations, which may eventually increase shell availability for these opportunistic snakes. Education efforts in local communities emphasize the ecological importance of both turtles and snakes in maintaining healthy aquatic ecosystems, helping to reduce persecution and harvest of these reptiles. The future prospects for shell-dwelling snake populations remain uncertain, heavily dependent on broader conservation success in preserving Southeast Asian wetlands against development pressures and climate change impacts. Recent protected area designations in key wetland regions of Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam offer hope that these fascinating creatures will continue their remarkable shell-dwelling lifestyle for generations to come.

Conclusion

The remarkable adaptation of Asian mud snakes to utilize abandoned turtle shells illustrates nature’s incredible capacity for innovation through evolutionary processes. This behavior represents more than just a curious ecological footnote—it demonstrates how species can develop specialized strategies that connect them to other animals in unexpected ways. As wetland ecosystems face increasing pressure from human development and climate change, the fate of these unique shell-dwelling snakes remains uncertain. Their story reminds us that conservation efforts must consider not just individual species but the complex ecological relationships that sustain them. By preserving the environments where turtles and snakes coexist, we ensure that this fascinating example of natural ingenuity continues to enrich our understanding of the natural world.