Throughout human history, snakes have slithered their way into our collective consciousness as symbols of tremendous power and mystique. These legless reptiles have inspired both fear and reverence, becoming central figures in religious practices across cultures spanning six continents. From the cobras adorning ancient Egyptian crowns to the python deities of West Africa, snake worship—also known as ophiolatry—represents one of humanity’s oldest and most enigmatic spiritual traditions. These serpentine devotions often transcend simple animal worship, instead embodying complex cosmological beliefs about fertility, rebirth, wisdom, and the underworld. As we explore these mysterious practices, we’ll uncover how these reptiles became divine messengers, healers, protectors, and sometimes harbingers of destruction in the eyes of their devoted followers.

The Ancient Serpent Gods of Mesoamerica

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, snake deities occupied the highest echelons of divine hierarchies. The Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, depicted as a feathered serpent, represented wisdom, creation, and the morning star Venus. His worship extended across multiple civilizations, appearing as Kukulkan among the Maya and Gucumatz to the K’iche’ people. Archaeological evidence from Teotihuacan reveals elaborate temples adorned with feathered serpent motifs dating back to 100 CE, demonstrating the longevity of this worship. During ceremonial events, priests would sometimes dress in elaborate serpent regalia, wearing headdresses depicting open serpent jaws and ceremonial garments patterned with scales to channel the divine reptilian energy.

India’s Naga Worship: From Ancient Texts to Modern Festivals

The worship of Nagas—divine serpent beings—has persisted in India for millennia, receiving mention in ancient Vedic texts as protectors of water sources and bearers of fertility. These serpent deities are believed to reside in the netherworld, emerging occasionally to interact with humans, and in some traditions, intermarrying with human royal bloodlines. The festival of Nag Panchami remains one of India’s most vibrant snake worship traditions, during which devotees offer milk to live cobras and snake images at temples and household shrines. In some communities, particularly in rural areas, snake charmers are invited to bring live cobras to homes for direct worship, where the serpents receive offerings of milk, turmeric, and flowers while families pray for protection from snake bites and other misfortunes.

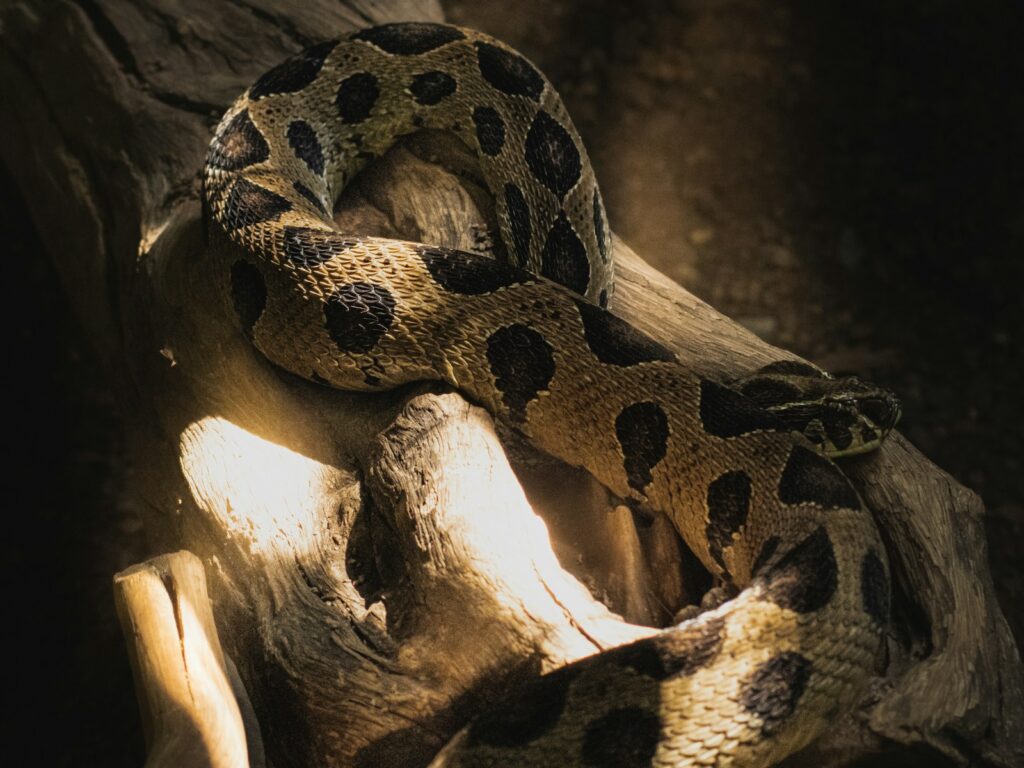

The Python Cult of Ancient Benin

In the kingdom of Dahomey (present-day Benin), the python deity Dangbé received elaborate worship through a dedicated priesthood and temple complex at Ouidah. This serpent god was considered the physical embodiment of cosmic power, with royal authority itself deriving from the divine serpent. The Python Temple housed dozens of living royal pythons that priests cared for as physical manifestations of the deity, allowing devotees to touch them for blessings and healing. Even today, descendants of these practitioners maintain a sacred forest where pythons are protected, and killing these snakes—even accidentally—requires elaborate purification rituals and financial payments to the temple. The python cult became so influential that it successfully resisted early Christian missionary efforts, eventually resulting in syncretic practices that blended traditional serpent veneration with Catholic elements.

Greek Mystery Cults and the Serpent of Renewal

Ancient Greece harbored several mystery religions featuring serpent symbolism, most notably in Dionysian rituals and the healing cult of Asclepius. At Asclepian healing temples, non-venomous snakes slithered freely among sleeping patients, their touch considered therapeutic and their movements interpreted as divine guidance. Priestesses of the Dionysian mysteries would handle live snakes during ecstatic rituals, demonstrating their divine possession and connection to chthonic forces. Archaeological evidence from these mystery cults includes ritual vessels shaped like snakes and ceremonial staffs entwined with serpent imagery, suggesting the central role these reptiles played in transformative religious experiences. The Greeks viewed the snake’s ability to shed its skin as the ultimate symbol of renewal and resurrection—a powerful metaphor that influenced their understanding of healing, rebirth, and transcendence.

The Snake-Handling Churches of Appalachia

Perhaps the most dangerous contemporary snake worship practice exists within certain isolated Pentecostal churches in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. Followers interpret biblical passages like Mark 16:18 (“they shall take up serpents”) as a divine command to handle venomous snakes during religious services. During these intense worship services, practitioners enter ecstatic states while handling eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, timber rattlers, and copperheads with bare hands, believing divine protection will prevent bites or render venom harmless. The tradition began in the early 20th century with George Went Hensley, who first incorporated snake handling into church services around 1909, and despite numerous deaths—including Hensley’s own fatal snakebite in 1955—the practice continues in remote churches. Several states have outlawed religious snake handling, driving these congregations underground while simultaneously strengthening practitioners’ sense of persecution and religious commitment.

Australia’s Rainbow Serpent: Aboriginal Dreamtime Creator

In Australian Aboriginal spirituality, the Rainbow Serpent represents one of the most powerful creator beings from the Dreamtime—the primordial era when the world was formed. This massive serpent deity is believed to have shaped the landscape by carving rivers and mountains with its enormous body as it slithered across the featureless earth. Different Aboriginal groups tell variations of Rainbow Serpent stories, but most associate it with water, rain, and fertility, making it both life-giving and potentially destructive during floods. The Rainbow Serpent appears in some of humanity’s oldest religious artwork, featuring prominently in Aboriginal rock paintings dating back over 6,000 years in Arnhem Land and other regions. Many Aboriginal communities maintain strict taboos around certain water sources believed to house the Rainbow Serpent, requiring specific permissions and ritual preparations before approaching these sacred sites.

Vodou and the Serpent Loa Damballa

In Haitian Vodou, the serpent loa (spirit) Damballa represents one of the most revered and powerful deities in the pantheon. Depicted as a great white serpent or sometimes as a rainbow, Damballa embodies divine wisdom, creation, and purity as the oldest ancestral spirit. During ceremonies honoring Damballa, devotees draw elaborate vévé (ritual symbols) using cornmeal or flour, often depicting serpentine patterns, and offer white foods such as eggs and milk. The possession trance induced by Damballa is particularly distinctive, with the devotee moving sinuously like a snake, sometimes climbing trees or posts and speaking in hissing whispers. Practitioners believe Damballa created the cosmos by using his 7,000 coils to form the stars and planets, after which he retreated into the primordial waters, emerging occasionally to communicate with humanity through possessed devotees.

The Ndebele Snake Healers of Southern Africa

Among the Ndebele people of Zimbabwe and South Africa, specialized traditional healers known as izangoma maintain sacred relationships with serpents, particularly pythons. These snake doctors undergo intense initiatory experiences often involving dreams or visions of snakes entering their bodies, which is interpreted as ancestral spirits choosing them for healing work. After initiation, many izangoma keep live pythons in their healing huts, using them as diagnostic tools by observing how the snake moves around or reacts to patients. The most powerful healers claim the ability to transform themselves into pythons or to send their serpent familiars to gather information or perform healing at a distance. Many izangoma wear elaborate beaded regalia featuring serpentine patterns and carry ceremonial staffs adorned with python vertebrae, symbolizing their connection to the reptilian healing powers.

Indonesia’s Tengger Snake Rituals

On the slopes of Mount Bromo in East Java, the Tengger people maintain unique snake rituals related to agricultural fertility and ancestral communication. During certain full moon ceremonies, specially trained priestesses enter trance states and handle multiple species of snakes, including occasionally venomous ones, while reciting ancient mantras believed to activate the reptiles’ spiritual powers. These rituals typically coincide with planting seasons, as snakes are seen as representatives of underground forces that control soil fertility and crop success. According to Tengger belief, their ancestors can temporarily inhabit the bodies of certain snakes to deliver warnings or blessings to the community, with the snake’s movement patterns being carefully interpreted by spiritual leaders. Traditional healers in the region also use snake parts—including shed skins, fangs, and specially prepared venom—in medicines believed to cure various ailments, particularly those related to skin conditions and fertility issues.

The Ancient Egyptian Cobra Goddess Wadjet

Ancient Egyptian religion featured multiple serpent deities, but none more prominent than Wadjet, the cobra goddess who served as protector of Lower Egypt and the pharaoh. Wadjet appeared on the pharaonic crown as the uraeus—a rearing cobra ready to strike enemies of the king—symbolizing the ruler’s divine authority and protective power. Temple complexes dedicated to Wadjet featured live cobras tended by specialized priestesses who interpreted the snakes’ movements as omens and divine communications. Archaeological evidence suggests that some temple cobras received elaborate mummification upon death, with snake mummies placed in gilded coffins alongside offerings of milk and honey. The veneration of Wadjet became so culturally entrenched that when Christianity later spread through Egypt, aspects of her protective imagery influenced Coptic iconography, demonstrating the remarkable persistence of serpent symbolism across religious transitions.

China’s White Snake Goddess and Temple Practices

The legend of the White Snake, a powerful female serpent deity who took human form, has inspired temple worship practices throughout China for centuries, particularly around West Lake in Hangzhou. This story of a snake spirit who falls in love with a human pharmacist and achieves enlightenment has spawned numerous temples where devotees seek blessings related to love, fertility, and healing. At these temples, elaborate ceremonies involving white silk offerings, snake-shaped lanterns, and specially prepared incense create a sensory environment believed to attract the White Snake’s benevolent attention. Some traditional temple practices include the ritual feeding of white snakes kept within temple grounds, though most modern celebrations have replaced live snakes with elaborate carved representations. The White Snake Festival, celebrated annually on the eighteenth day of the fifth lunar month, features boat processions on West Lake, opera performances retelling the serpent goddess’s story, and midnight offerings at lakeside shrines.

The Abeokuta Thunder and Snake Cult of Nigeria

In southwestern Nigeria, particularly around the city of Abeokuta, the Yoruba maintain one of Africa’s most complex serpent worship systems through the veneration of Oshunmare, a deity representing the rainbow python who connects earth and heaven. This worship intertwines with the cult of Shango, the thunder deity, as the two forces are considered cosmologically balanced—the airborne lightning and the earthbound serpent representing complementary spiritual powers. During major ceremonies held at the beginning of the rainy season, initiates undergo elaborate possession rituals where they embody serpent movements and behaviors, sometimes entering burrows or climbing sacred trees while in trance states. Traditional priesthood training requires aspirants to spend extended periods in sacred groves where venomous snakes are protected, demonstrating their divine calling by handling serpents without harm. The community maintains strict taboos against killing certain snake species, particularly pythons and certain vipers, with the belief that violating these prohibitions will result in drought or excessive, destructive rainfall.

Contemporary Snake Worship at Maria Lionza Shrines

In Venezuela, the syncretic spiritual tradition centered around the goddess Maria Lionza incorporates serpent veneration drawn from indigenous, African, and Catholic elements. Devotees gather at mountain shrines in Sorte Mountain National Park, where serpent rituals involve the handling of both live snakes and elaborate serpent effigies during healing ceremonies and spiritual consultations. Medium practitioners enter trance states to channel serpent spirits, offering healing and divination services to pilgrims seeking interventions for health, financial, or relationship problems. These snake rituals have adapted to contemporary concerns, with some modern practitioners focusing on environmental protection of endangered snake species or addressing specific community issues through serpent-centered spiritual work. The tradition has shown remarkable resilience, evolving from a local indigenous practice to a national spiritual movement with millions of followers, many of whom maintain home altars featuring serpent imagery alongside Catholic saints and indigenous spirit figures.

Philosophical Underpinnings of Serpent Veneration

Beyond specific cultural practices, snake worship around the world shares remarkable philosophical similarities that suggest deeper psychological and spiritual patterns in human relationship with these creatures. The snake’s limbless form and fluid movement create an immediate sensory impression of otherness—neither fish nor typical land animal—placing them in a liminal category that has historically made them perfect vessels for concepts of transformation and mediation between worlds. Their ability to shed skin intact represents one of nature’s most visible symbols of renewal and rebirth, making them natural emblems for spiritual transformation across diverse cultures. The duality of serpents—potentially deadly yet beneficial in controlling rodent populations, mysterious yet familiar—mirrors humanity’s complex relationship with sacred power itself: simultaneously attractive and dangerous, necessary yet requiring careful handling. These philosophical underpinnings help explain why snake symbolism appears so consistently in spiritual systems worldwide, transcending geographic isolation and suggesting a deep-rooted human tendency to assign cosmic significance to these remarkable reptiles.

From ancient temple complexes housing sacred cobras to modern Pentecostal churches where rattlesnakes are handled in ecstatic worship, snake veneration represents one of humanity’s most enduring spiritual traditions. These practices reveal a fascinating intersection between human psychology, cultural evolution, and our complex relationship with the natural world. Whether seen as divine messengers, ancestors, healing forces, or cosmic creators, serpents continue to occupy a unique position in religious consciousness worldwide. As many of these traditions face pressure from modernization, urbanization, and changing religious landscapes, their documentation and study becomes increasingly important for understanding this significant aspect of human spiritual expression. The persistence of snake symbolism across time and culture suggests these sinuous reptiles will likely remain powerful spiritual symbols for generations to come, continuing to inspire both fear and reverence in equal measure.