When most people think of venomous snakes, they imagine aggressive, striking reptiles poised to attack at any moment. However, the reality is far more nuanced. Many venomous snake species are remarkably reluctant to bite humans, preferring to flee or use other defensive tactics before resorting to their venomous capabilities. These less aggressive venomous snakes often get overlooked in discussions about snake behaviour, yet understanding their typically docile nature can help dispel unnecessary fears and promote conservation efforts. This article explores some of the world’s least aggressive venomous snakes, examining their behaviors, habitats, and the circumstances under which they might—rarely—choose to bite.

Hognose Snakes: Dramatic Actors of the Snake World

The Eastern Hognose Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) and its relatives are perhaps nature’s most theatrical reptiles, employing an elaborate repertoire of defensive behaviors before ever considering a venomous bite. When threatened, these snakes first flatten their necks and hiss loudly, mimicking more dangerous cobra species. If this initial display fails to deter a predator, hognose snakes engage in a remarkable death-feigning behavior—rolling onto their backs, mouth agape, and sometimes emitting a foul-smelling musk to complete the illusion. Despite possessing rear fangs and mildly toxic venom used primarily for subduing prey, hognose snakes rarely bite humans, with some handlers reporting having never received a defensive bite despite years of interaction. Their venom is considered medically insignificant to humans, causing at most local swelling and discomfort rather than serious effects.

Rinkhals: The Spitting Cobra That Prefers Not to Bite

The Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus), sometimes called the Ring-necked Spitting Cobra, employs a fascinating defensive strategy that actually minimizes physical contact with threats. Native to southern Africa, this cobra relative can spray its venom accurately at a predator’s eyes from distances up to 2.5 meters (8 feet), causing painful but typically temporary blindness if not washed out promptly. This remarkable adaptation allows the snake to defend itself without risking close combat that might lead to injury. Before resorting to spitting, Rinkhals typically display warning behaviors including raising their hood and performing mock strikes with closed mouths. Despite their fearsome capabilities, Rinkhals are surprisingly reluctant biters, preferring to flee or use their spitting defence rather than delivering a venomous bite, making actual envenomations relatively uncommon compared to other venomous species in their range.

Coral Snakes: Brightly Colored but Bashful

Coral snakes, belonging to the Elapidae family and including genera such as Micrurus in the Americas, are instantly recognizable by their vibrant red, yellow/white, and black banding patterns that serve as a warning to potential predators. Despite possessing highly potent neurotoxic venom, coral snakes are notoriously shy and non-confrontational creatures that spend much of their time hidden underground or beneath forest debris. Their small mouths and relatively short fangs make it difficult for them to deliver an effective bite to humans unless they are handled directly or accidentally stepped on. Coral snake bites to humans are exceedingly rare, with some species going decades without a documented case of human envenomation. When confronted, these snakes typically attempt to escape first, resorting to biting only when physically restrained or when they have no escape route.

Vine Snakes: Slender Tree-Dwellers with Gentle Dispositions

Vine snakes (including species from the genera Ahaetulla and Oxybelis) are remarkably slender, often bright green arboreal snakes adapted to life among the branches and foliage of trees. These rear-fanged venomous snakes possess mild venom primarily used to subdue small prey like lizards and frogs rather than for defence. Their extremely thin bodies, sometimes just pencil-width, and extraordinary length create a distinctive appearance that helps them blend perfectly with vines and branches. When encountered, vine snakes typically freeze in place, relying on their excellent camouflage rather than aggressive defensive behaviors. Most specimens rarely attempt to bite even when handled, though they may gape their mouths in a threat display, showing their characteristic pointed snouts and sometimes exposing a colorful lining inside their mouths. Bites from vine snakes, when they do occur, generally produce only minor local symptoms in humans.

Copperheads: North America’s Reluctant Biters

The Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) stands out among North American pit vipers for its notably less aggressive demeanor compared to rattlesnakes or cottonmouths. These beautifully patterned snakes with distinctive hourglass-shaped crossbands rely heavily on their exceptional camouflage as a first line of defense, often remaining perfectly still when encountered rather than fleeing or striking. Research has demonstrated that copperheads frequently employ “dry bites” when defensive, striking without injecting venom approximately 25% of the time, which conserves their metabolically expensive venom for hunting. When stepped on or directly handled, copperheads may bite defensively, but they typically give little or no warning before doing so, lacking the dramatic rattling or body positioning displays of their relatives. Despite being responsible for more venomous snakebites in the eastern United States than any other species (primarily due to their abundance and overlap with human habitation), copperheads rarely deliver fatal bites, with their venom being less potent than many other pit vipers.

King Cobras: Surprisingly Calculated Defenders

Perhaps surprisingly, the King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), the world’s longest venomous snake, has earned a reputation among professional handlers and field herpetologists for its relatively calm and calculated defensive behavior. Despite their intimidating size—reaching lengths of 18 feet—and their ability to raise the front third of their body off the ground while displaying their impressive hood, king cobras typically attempt to avoid human confrontation whenever possible. These intelligent snakes often give clear warning signals before striking, including their distinctive hood display and a unique growling hiss that differs from other snake species. Field researchers have documented numerous encounters where king cobras have had opportunities to strike but chose to retreat instead. When they do deliver defensive bites, king cobras have been observed to deliver measured “dry bites” without injecting venom, demonstrating a level of control that contradicts their fearsome reputation.

Mambas: Misunderstood Speed Demons

Mambas, particularly the Black Mamba ( Dendroaspis polylepis ), have perhaps the most undeservedly aggressive reputation of any venomous snake, often portrayed in media as aggressive hunters of humans. The reality is considerably more nuanced, with these highly alert and nervous snakes preferring flight over fight in almost all human encounters. Their extraordinary speed—up to 12.5 miles per hour in short bursts—serves primarily as an escape mechanism rather than an offensive capability. When cornered without escape options, mambas can indeed become defensive, raising the front portion of their body, flattening their neck into a slight hood, and opening their mouth to display the black lining that gives the black mamba its name. Herpetologists who work with these snakes report that they give ample warning before striking and will typically only bite as a last resort when they perceive no escape route. Their defensive strikes are usually lightning-fast and precise, but many recorded bites occur when the snakes are accidentally stepped on or encountered in confined spaces where they cannot retreat.

Western Hognose Snake: The Ultimate Bluffer

The Western Hognose Snake ( Heterodon nasicus ) takes non-aggressive defense to theatrical extremes that make it one of the most fascinating venomous snakes to observe. When threatened, this small, stout-bodied snake goes through an elaborate bluffing routine that starts with flattening its head and neck while hissing loudly and making mock strikes with a closed mouth. If this performance fails to deter a predator, the western hognose escalates to one of the most convincing death-feigning displays in the reptile world—rolling onto its back, writhing dramatically, and then going completely limp with its mouth open and tongue hanging out. This performance often includes the release of a foul-smelling musk and fecal matter to complete the illusion of death. Despite being technically venomous with enlarged rear fangs and a mild toxin that helps subdue prey, western hognose snakes rarely attempt to bite humans even when handled, and their venom poses virtually no medical significance to people beyond possible mild allergic reactions in particularly sensitive individuals.

Mangrove Snake: The Gentle Giant

The Mangrove Snake (Boiga dendrophila), also known as the Gold-ringed Cat Snake, combines striking beauty with a surprisingly docile temperament despite its venomous capabilities. These large rear-fanged snakes, reaching lengths of up to 8 feet, display a stunning pattern of glossy black scales highlighted with bright yellow bands. Native to Southeast Asian mangrove forests and nearby habitats, these primarily arboreal snakes possess a mild venom delivered through enlarged rear fangs that require a chewing motion rather than the immediate injection typical of front-fanged species. When encountered in the wild, mangrove snakes typically attempt to retreat or remain motionless, relying on their cryptic coloration among dappled forest light. Even when handled, many specimens show remarkable tolerance before resorting to defensive biting, though individual temperaments can vary considerably. Their venom, while capable of causing localized swelling and discomfort, rarely results in serious medical consequences for humans, making them popular in the exotic pet trade despite the potential risks associated with any venomous species.

Opisthoglyphous Snakes: The Mild-Mannered Rear-Fanged Group

Opisthoglyphous snakes—those with enlarged venom-delivering teeth located at the rear of their upper jaw—typically demonstrate less aggressive defensive behaviors than their front-fanged counterparts. This diverse group includes many colubrids such as the Brown Tree Snake ( Boiga irregularis ), Boomslang (Dispholidus typus), and various species of vine snakes and cat snakes. Their rear-fang dental arrangement requires them to “chew” venom into prey or potential threats, making defensive bites less immediately effective and perhaps contributing to their generally more reserved defensive strategies. Many opisthoglyphous species rely heavily on camouflage and remaining motionless when detected, only attempting to bite when physically restrained or directly handled. This pattern of behaviour makes sense evolutionarily, as their venom delivery system is more specialized for subduing prey than for immediate defence. While some members of this group, like the Boomslang, possess dangerously potent venom, the majority have relatively mild venoms of limited medical significance to humans, and their reluctance to bite makes envenomation events exceptionally rare.

Green Tree Python: Minimal Aggression Despite Venomous Capabilities

The Green Tree Python (Morelia viridis), while primarily considered a constrictor, possesses enlarged rear teeth and mild venom-like toxic saliva that technically places it among mildly venomous species. These stunningly beautiful emerald snakes are renowned for their sedentary lifestyle, often remaining coiled around the same branch for days or even weeks at a time. When encountered in the wild, green tree pythons typically rely on their exceptional camouflage rather than aggressive displays, remaining perfectly still even when approached closely by potential threats. Their characteristic defensive posture involves remaining tightly coiled with their head tucked securely in the middle of their body loops, making it difficult for predators to target this vulnerable area. Even when disturbed, many specimens will retreat their head further into their coils rather than striking outward, demonstrating a clear preference for defensive rather than aggressive responses. While capable of delivering painful bites with their long, recurved teeth, green tree pythons rarely bite defensively unless directly handled or physically threatened, making them one of the least aggressive of all mildly venomous snake species.

Tentacled Snake: The Aquatic Ambush Specialist

The Tentacled Snake (Erpeton tentaculatum) represents perhaps the least aggressive venomous snake species in the world, with virtually no recorded instances of defensive biting toward humans. These highly specialized aquatic snakes, native to Southeast Asian freshwater habitats, possess a mild venom delivered through enlarged rear fangs that they use exclusively for immobilizing fish prey. The most distinctive feature of these unusual snakes is the pair of sensory tentacles extending from their snout that help detect the movement of fish in murky water. When encountered by humans, tentacled snakes typically remain motionless, relying on their exceptional camouflage that mimics waterlogged branches or aquatic vegetation. Even when handled—which should always be avoided with any potentially venomous species—tentacled snakes rarely attempt to bite, instead remaining rigid in their characteristic J-shaped hunting posture. Their extreme specialization for aquatic life and fish predation appears to have rendered aggressive defensive behaviors unnecessary, as they simply lack the physical capabilities to effectively defend themselves against large terrestrial predators like humans.

Factors Influencing Defensive Behavior in Venomous Snakes

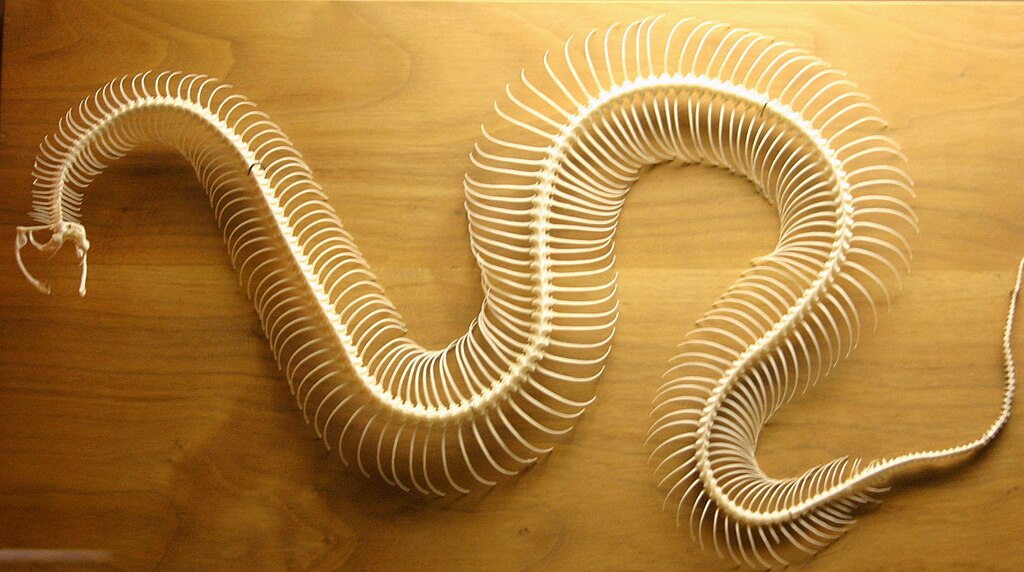

Understanding why certain venomous snakes display less aggressive tendencies requires examining multiple biological and ecological factors that shape their defensive strategies. A snake’s body morphology plays a crucial role—slender-bodied species like vine snakes are physically more vulnerable to injury during confrontations and thus typically favor flight over fight responses. Habitat specialization also strongly influences behavior, with arboreal species generally displaying less aggression than terrestrial species, possibly because tree-dwelling snakes can more effectively escape vertically from ground-based predators. Evolutionary history matters significantly, as species that evolved alongside predators capable of killing them despite their venom often develop alternative defensive strategies beyond simply striking. Individual variation within species cannot be overlooked, with factors such as age, reproductive status, recent feeding, and previous experiences with threats all potentially affecting how aggressively a snake responds to perceived danger. Perhaps most importantly, most snake species have evolved to conserve their metabolically expensive venom primarily for prey acquisition rather than defense, explaining why many species demonstrate remarkable restraint before resorting to venomous bites.

Conclusion

Venomous snakes comprise a diverse group of reptiles with widely varying defensive behaviors that rarely match their fearsome reputations. The least aggressive species featured in this article demonstrate that possession of venom doesn’t necessarily correlate with a propensity to bite humans. From the theatrical death-feigning displays of hognose snakes to the still, cryptic defenses of vine snakes, these animals have evolved sophisticated alternatives to aggressive confrontation. Understanding the typically non-aggressive nature of most venomous snakes can help foster a more balanced perspective on these important predators, potentially reducing unnecessary killings motivated by fear. While all venomous snakes deserve respect and appropriate caution, recognizing that most species prefer retreat over confrontation can help humans and snakes better coexist in shared environments.