Encountering wildlife can be a fascinating experience, but it also comes with responsibility. When you spot a snake in its natural habitat, it may not always be immediately obvious whether the animal is healthy or suffering from an injury. Identifying an injured snake requires careful observation and knowledge of normal snake behavior and appearance. This article provides comprehensive guidance on recognizing signs of injury in wild snakes, understanding when intervention might be necessary, and knowing how to respond appropriately if you encounter an injured reptile. Whether you’re a hiker, nature enthusiast, or someone who frequently encounters wildlife, these insights can help you make informed decisions that respect both the animal’s wellbeing and natural ecological processes.

Understanding Normal Snake Behavior

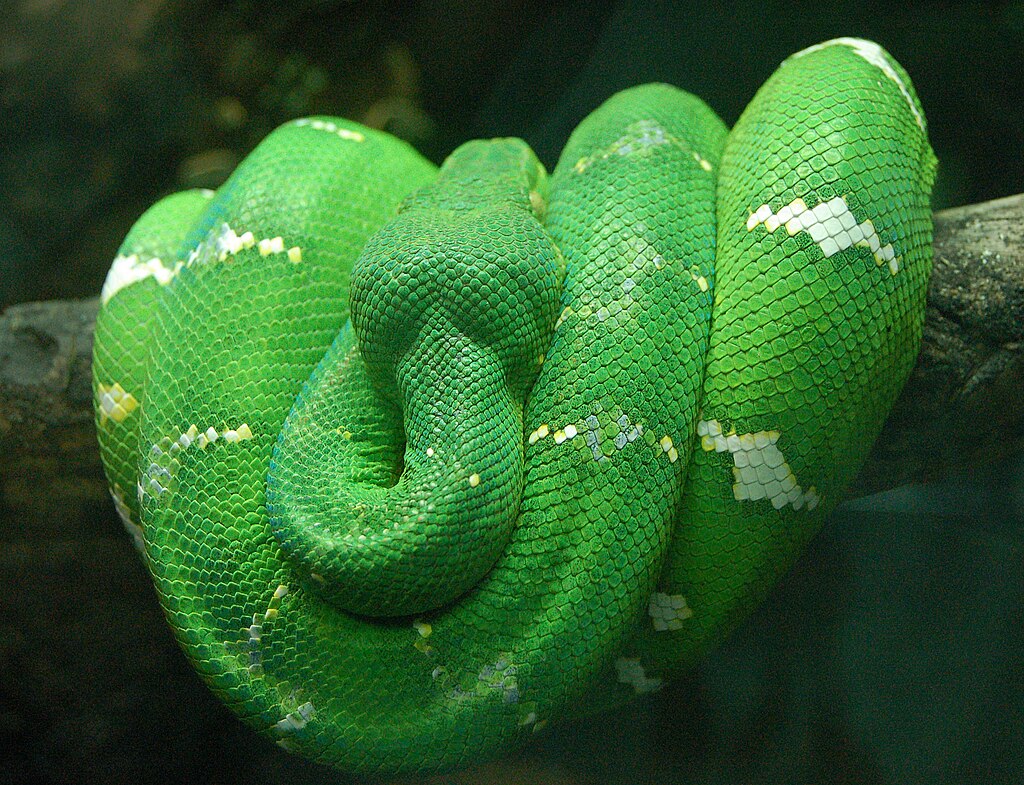

Before you can identify an injured snake, you need to understand what constitutes normal behavior for these reptiles. Healthy snakes typically move with fluid, purposeful movements, exhibiting smooth locomotion appropriate to their species. When undisturbed, most snakes will either remain still to conserve energy or move deliberately toward shelter, basking spots, or potential prey. Their tongue will flick regularly as they use their vomeronasal organ (Jacobson’s organ) to sample chemicals in their environment, essentially “tasting” the air to gather information. A healthy snake will also typically respond to your presence by either fleeing or adopting a defensive posture, depending on the species and situation – complete indifference to potential threats often suggests something may be wrong.

Abnormal Posture and Movement Patterns

Injured snakes frequently exhibit unusual postures or movement patterns that deviate from their normal locomotive behavior. A snake that’s dragging part of its body, moving in circles, or unable to right itself when placed on its back may have suffered spinal damage or neurological issues. Some injured snakes may move with jerky, uncoordinated movements rather than the smooth, flowing motion typical of healthy individuals. Stargazing behavior, where a snake seems unable to control its neck muscles and points its head upward in an unnatural position, can indicate serious neurological problems from injury or disease. Additionally, a snake that’s coiled in an asymmetrical fashion or seems to favor one side of its body often has sustained some form of physical trauma to the affected area.

Visible External Wounds and Bleeding

Perhaps the most obvious sign of injury in a wild snake is the presence of visible external wounds or bleeding. These might appear as cuts, punctures, abrasions, or areas where scales have been torn away, exposing the flesh underneath. Fresh wounds will typically show some degree of bleeding, which can range from minor seepage to concerning hemorrhage. Older injuries may appear as scabbed areas, discolored patches, or irregularities in the scale pattern. Wounds around the head area are particularly concerning, as they can affect the snake’s ability to feed or sense its environment. Burns, which might result from wildfires or human activities, often appear as blistered areas or patches where scales appear melted or fused together.

Swelling and Unusual Lumps

Abnormal swelling or unusual lumps on a snake’s body often indicate injury or health problems that require attention. These swellings might result from fractures, internal bleeding, infection, or even parasitic conditions that have weakened the animal. A particularly concerning sign is segmental swelling, where a specific section of the snake’s body appears disproportionately enlarged compared to the rest. Swelling around joints or in the middle of body segments may indicate broken bones or internal trauma. In some cases, you might notice a snake’s body kinked at an unusual angle where swelling is present, suggesting a potential fracture underneath the scales.

Respiratory Distress Signs

Snakes suffering from respiratory issues often exhibit visible signs of distress that can indicate injury, particularly if they’ve inhaled water or smoke, or suffered trauma to their single functional lung. Open-mouth breathing, wheezing, bubbling around the mouth, or audible respiratory sounds are all concerning symptoms in a wild snake. You might notice the snake’s breathing appears labored, with exaggerated body movements during respiration or gaping behavior where they hold their mouth open to facilitate breathing. In severe cases, a snake may extend its neck upward in an attempt to create a straighter airway, similar to how humans might sit upright during an asthma attack. These signs are particularly urgent if observed in conjunction with other symptoms of injury, as respiratory compromise can rapidly become life-threatening for reptiles.

Dehydration and Emaciation Indicators

Injured snakes often become dehydrated and emaciated as their condition prevents normal hunting, feeding, or access to water sources. Signs of dehydration include sunken eyes, loose, wrinkled skin lacking elasticity, and a generally desiccated appearance. The snake’s body may appear triangular in cross-section rather than rounded, indicating significant muscle loss and dehydration along the spine. In cases of prolonged injury or illness, you might observe a visible “waist” behind the head where the neck meets the body, indicating significant weight loss. Severely injured snakes may display prominent spine ridges or visible ribs through their scales, clear indicators that the animal hasn’t been able to maintain normal nutrition for an extended period.

Abnormal Discharges and Secretions

Healthy snakes typically don’t produce visible discharges or secretions except during specific activities like shedding. Any unusual discharge from the mouth, nostrils, cloaca, or wounds can indicate infection resulting from injury. You might observe mucus, pus, blood, or abnormally colored fluids emanating from these openings. Mouth rot (infectious stomatitis) appears as cheese-like material in the mouth, often with associated swelling of the oral tissues, and commonly develops after facial injuries or systemic weakening. Foul-smelling discharges almost always indicate infection and require urgent intervention. Even clear discharges from the nose or mouth are abnormal in snakes and may suggest respiratory infection or injury to the respiratory tract.

Incomplete or Difficult Shedding

While not always directly caused by injury, difficulty shedding (dysecdysis) can indicate an injured snake or can result from physical damage to the skin or scales. A healthy snake typically sheds its skin in one complete piece, starting from the head and peeling backward like a sock turned inside out. An injured snake may retain patches of old skin, particularly over wounded areas, or may have an incomplete or piecemeal shed pattern. Eye caps (spectacles) that fail to shed properly might indicate head trauma or dehydration from injury. Snakes with severe injuries often lack the strength or mobility to rub against surfaces to initiate and complete the shedding process, leading to multiple layers of retained shed that can constrict blood flow and cause further complications.

Unusual Defensive Responses

Injured snakes often display defensive behaviors that differ from those of healthy individuals of the same species. While healthy snakes typically flee from potential threats or display species-appropriate defensive postures, injured individuals may be unable to escape and might resort to more aggressive displays as a last resort. Conversely, some injured snakes become entirely unresponsive to stimuli that would normally trigger defensive behavior, suggesting neurological damage or extreme weakness. A snake that allows close approach without reaction or fails to display typical defensive posturing when handled is likely suffering from significant injury or illness. Some injured snakes may strike repeatedly but with poor aim or coordination, indicating neurological impairment affecting their defensive capabilities.

Evidence of Predator Attacks

Many wild snake injuries result from unsuccessful predation attempts, and recognizing these patterns can help identify wounded animals. Puncture wounds arranged in patterns consistent with bird talons, mammalian teeth, or other predator weapons often indicate a snake that narrowly escaped becoming prey. Partial tail loss, while sometimes healed over in older injuries, represents a common predator-induced trauma that can affect the snake’s mobility and hunting capabilities. Some snakes exhibit scale damage or abrasions consistent with being constricted by larger snakes or gripped by predatory birds. In freshly injured snakes, you might observe saliva residue or distinctive tooth/claw marks around wound sites that help identify the type of predator involved.

Human-Caused Injury Patterns

Unfortunately, many wild snake injuries result directly from human activities, and these often have distinctive patterns. Lacerations with unusually straight edges may indicate encounters with lawn equipment, agricultural machinery, or deliberate cutting with tools. Road injuries typically present as crushing trauma, often with extensive internal damage despite sometimes minimal external evidence beyond unusual body positioning. Snakes entangled in netting, plastic rings, or other human debris may show distinctive constriction wounds or necrotic tissue where circulation was compromised. Burns from discarded cigarettes, controlled burns, or encounters with hot surfaces like roads in summer have a characteristic appearance with blistered or sloughing skin that differs from typical predator-induced wounds.

When and How to Intervene

Determining whether to intervene when you encounter an injured wild snake requires careful consideration of several factors. Minor injuries in otherwise alert and active snakes often heal naturally without human assistance, as reptiles possess remarkable regenerative capabilities. However, severe injuries, especially those involving the spine, respiratory system, or extensive wounds, typically warrant intervention by wildlife rehabilitation specialists. If you decide intervention is necessary, prioritize your safety first – even injured venomous species remain potentially dangerous. Capture and transport should minimize further stress by using a secure, ventilated container with a small amount of substrate and a hiding place. Always contact a wildlife rehabilitator or veterinarian experienced with reptiles before attempting to provide first aid, as improper treatment can worsen the animal’s condition.

The Recovery Process for Wild Snakes

The rehabilitation journey for an injured wild snake is often complex and highly dependent on the nature and severity of the injury. Under professional care, wounded snakes typically require a carefully controlled environment with optimal temperature gradients, appropriate humidity, minimal stress, and sometimes specialized nutrition through assist feeding. Veterinary treatment may include wound cleaning, antibiotics, pain management, and occasionally surgical intervention for severe cases. The recovery timeline varies dramatically – minor injuries might heal within weeks, while more serious trauma may require months of rehabilitation. Some injuries, particularly those affecting the spine or nervous system, may result in permanent disabilities that prevent release back to the wild, necessitating either humane euthanasia or permanent captive placement depending on quality of life assessments.

Wild snakes face numerous challenges in their natural environments, and injuries are unfortunately common occurrences in their lives. By understanding the signs that differentiate an injured snake from a healthy one, you can make informed decisions about when intervention might be appropriate. Remember that most wild snakes are protected by various laws and regulations, and handling them without proper permits can be illegal in many jurisdictions. If you do encounter an injured snake and determine that human assistance is warranted, always seek help from qualified wildlife rehabilitators or veterinarians with reptile experience. Your informed observation skills and appropriate response can make the difference between life and death for these important members of our ecosystem.