In the frost-rimmed world of Norse mythology, where gods and giants clashed beneath the sprawling branches of Yggdrasil, snakes and serpents slithered through the cosmic narratives with profound significance. Unlike many other ancient cultures that assigned primarily negative attributes to serpents, the Vikings maintained a complex and nuanced relationship with these creatures in their mythology. From the world-encircling Jörmungandr to the venomous serpents that tormented the god Loki, snakes represented both chaos and cosmic order, destruction and protection. Their sinuous forms coiled through Norse creation myths, doomsday prophecies, and everyday symbolism, reflecting the Vikings’ deep appreciation for nature’s dual capacity for beauty and terror. This exploration delves into the multifaceted representations of snakes in Norse mythology and their significance in Viking culture and belief.

Jörmungandr: The World Serpent

Perhaps the most famous serpent in Norse mythology is Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent. This colossal creature was one of three monstrous offspring of the trickster god Loki and the giantess Angrboða, alongside the wolf Fenrir and the half-dead goddess Hel. According to the ancient tales, Odin cast Jörmungandr into the great ocean surrounding Midgard (the realm of humans), where the serpent grew so enormous that it encircled the entire world and grasped its own tail in its mouth. This image of a serpent biting its tail, known as an ouroboros, symbolized the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth in many ancient cultures, including among the Norse. Jörmungandr’s presence in the ocean was both threatening and protective—while it represented a constant danger to the world of men, its encirclement also maintained cosmic boundaries and stability.

Jörmungandr and Thor: A Deadly Rivalry

The relationship between Thor, the thunder god, and Jörmungandr represents one of the most dramatic serpent-related narratives in Norse mythology. Their antagonism formed a central subplot that would ultimately culminate at Ragnarök, the Norse apocalypse. One famous tale recounts how Thor went fishing with the giant Hymir and used an ox head as bait to hook the Midgard Serpent. When Thor nearly pulled Jörmungandr from the depths, Hymir panicked and cut the fishing line, allowing the great serpent to escape. This fishing expedition foreshadowed their final confrontation during Ragnarök, when Thor would successfully slay Jörmungandr but then perish after taking nine steps, overcome by the serpent’s deadly venom. This mutual destruction narrative highlights the Norse concept of fate and inevitable doom, with the serpent serving as both Thor’s greatest enemy and his destiny.

Níðhöggr: The Corpse-Tearer

At the roots of Yggdrasil, the cosmic world tree connecting the nine realms of Norse cosmology, dwelled another significant serpent figure known as Níðhöggr (or Nidhogg). This malevolent dragon-serpent continuously gnawed at the roots of Yggdrasil, threatening the stability of the entire cosmos with its destructive behavior. According to the Poetic Edda, Níðhöggr fed on the bodies of the dead, particularly murderers, adulterers, and oath-breakers who ended up in Náströnd, a shore of corpses in the underworld. The great ash tree Yggdrasil would shudder when Níðhöggr shifted position, causing earthquakes in the world above. As an embodiment of decay and destruction, Níðhöggr represented the inevitable forces of entropy that would eventually contribute to the world’s destruction at Ragnarök.

Loki’s Punishment and the Venom-Dripping Serpent

One of the most vivid serpent images in Norse mythology appears in the story of Loki’s punishment. After orchestrating the death of the beloved god Baldr and subsequently mocking the other gods, Loki was captured and bound to three stones with the entrails of his own son, which the gods transformed into iron bonds. Above him, the goddess Skaði placed a venomous serpent that continuously dripped poison onto his face. Loki’s wife Sigyn loyally stood by him with a bowl to catch the venom, but whenever she had to empty the bowl, the poison would splash onto Loki’s face, causing him to writhe in agony and create earthquakes. This punishment was to last until Ragnarök, when Loki would break free to lead the forces of chaos against the gods. The serpent in this tale serves as an instrument of divine justice, inflicting constant suffering on the trickster who had disrupted cosmic order.

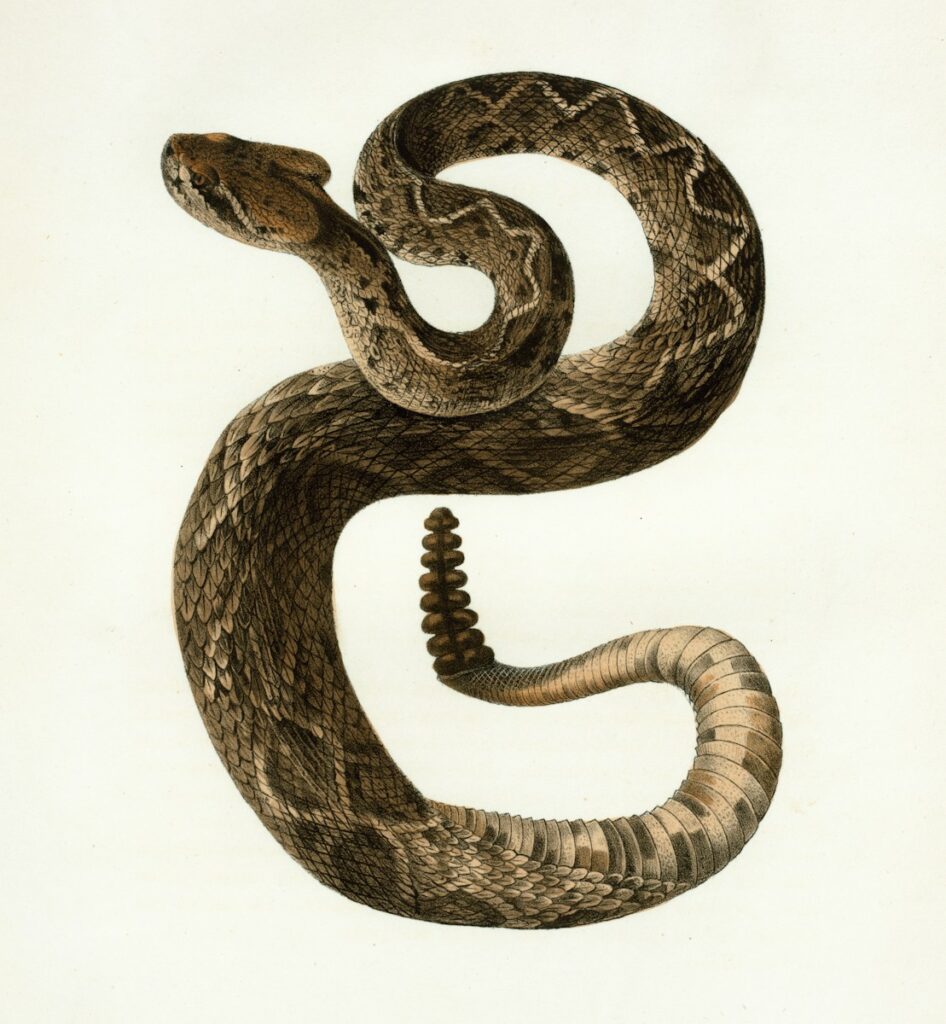

Serpents in Viking Art and Artifacts

Archaeological evidence confirms the cultural significance of serpents in Viking society through their prominent appearance in art and decorative objects. The sinuous, intertwining forms of serpents and dragons adorned everything from runestones and ship prows to jewelry and weapons. The “Urnes style,” the last phase of Viking animal art (named after carvings at Urnes Stave Church in Norway), featured elegant, ribbon-like animals and serpents with graceful curves and teardrop-shaped bodies. These artistic representations often blended serpentine imagery with other animals, creating complex zoomorphic designs that symbolized transformation and interconnectedness. Serpent motifs on weapons and armor may have been intended to invoke protection or strike fear into enemies, while those on domestic items and jewelry could represent household guardians or status symbols.

The Lindworm: A Norse Dragon-Serpent

The lindworm, a wingless serpentine dragon common in Scandinavian folklore and mythology, represented another important snake-like creature in the Norse imagination. Unlike the cosmic serpents such as Jörmungandr, lindworms often appeared in heroic sagas as monsters to be defeated, guarding treasure hoards or terrorizing communities. These creatures typically had two forelegs but no hindlegs, making them a hybrid between dragons and giant snakes. The famous Viking ship burial at Oseberg contained wooden carvings with lindworm motifs, suggesting their cultural importance. Later medieval Scandinavian folklore expanded on lindworm tales, including stories of how these creatures could form from a serpent that had lived for many years undisturbed or from an unfertilized egg kept warm by a woman.

Snakes and Rebirth Symbolism

The Norse, like many ancient cultures, recognized the snake’s ability to shed its skin as a powerful symbol of renewal and transformation. This natural phenomenon likely influenced the role of serpents in Norse creation myths and end-time prophecies, representing the cyclical nature of existence. After Ragnarök, when the world was destroyed and submerged under water, the Norse believed a new, verdant world would emerge—a cosmic rebirth paralleling the snake’s regenerative capabilities. The ouroboros image of Jörmungandr biting its own tail reinforced this cyclical worldview. Archaeological evidence has uncovered serpent imagery associated with burial sites, suggesting connections between snakes and concepts of afterlife or rebirth in Viking religious practices.

Serpents as Guardians of Wisdom and Knowledge

In Norse mythology, serpents sometimes functioned as guardians of secret knowledge or supernatural wisdom. The god Odin’s pursuit of wisdom often involved serpent symbolism, particularly in the tale of his sacrifice on Yggdrasil, where he hung for nine days pierced by his own spear. During this ordeal, he gazed down into the well of knowledge guarded by the serpent Níðhöggr, gaining profound cosmic insights. The association between serpents and knowledge appears in other Indo-European mythologies as well, suggesting shared ancient roots. The slithering movement of snakes, their ability to access both underground and aboveground realms, and their perceived watchfulness all contributed to their depiction as guardians of hidden truths and secret places in Norse mythology.

Snakes in Norse Magic and Medicine

Archaeological and textual evidence suggests that snakes played a role in Norse magical practices and early medicine. Runic inscriptions sometimes featured serpent imagery, possibly to enhance magical potency or provide protection. The medico-magical textual tradition that survived from the Norse period mentions snake parts used in healing concoctions for various ailments. The practice of “snake binding” appears in magical contexts, where symbolic or actual binding of snakes was thought to control negative forces. Snake venom, while deadly, was also recognized for its potential medicinal properties when properly prepared, reflecting the dualistic nature of serpents as both harmful and helpful entities in Norse understanding.

The Sea Serpent Tradition

Beyond the mythological Midgard Serpent, Norse folklore contained numerous accounts of enormous sea serpents inhabiting the cold northern waters. These creatures, while not necessarily part of the formal mythological tradition, represented a significant element of Viking maritime culture and informed their understanding of the ocean’s dangers. Norwegian fjords, with their deep, dark waters, were particularly associated with sea serpent sightings well into the modern era. Norse sailors developed elaborate traditions around avoiding and placating these creatures, including specific navigational practices and offerings. These beliefs reflect the Vikings’ intimate yet cautious relationship with the sea, their primary highway for trade, exploration, and conquest, where serpentine forms evoked both the dangers and mysteries of the deep.

Snakes in the Viking Afterlife Concepts

The Norse conception of the afterlife incorporated serpents in significant ways, particularly in the realms designated for those who did not die in battle. While warriors who died gloriously went to Valhalla or Fólkvangr, those who died of illness or old age might face serpents in Hel’s domain. According to the Prose Edda, the hall Náströnd (“Shore of Corpses”) in Hel featured walls woven from serpents whose heads faced inward, dripping venom onto the oath-breakers and murderers confined there. This image parallels Loki’s punishment and reinforces the serpent’s role as an instrument of justice in the Norse ethical framework. Even in death, the moral quality of one’s life determined whether serpents would be tormentors or potentially neutral entities in the afterlife.

Serpents and the Feminine in Norse Mythology

An intriguing aspect of Norse serpent symbolism is its occasional association with feminine power and magic. Several female figures in the mythology maintained connections to serpents, including the giantess Angrboða, who mothered Jörmungandr with Loki. The practice of seiðr, a form of magic associated primarily with women in Norse society, sometimes incorporated serpent symbolism in its rituals and paraphernalia. Archaeological evidence from female graves has revealed snake-shaped jewelry and amulets, suggesting possible connections between feminine spiritual power and serpentine imagery. This association contrasts with the masculine-coded confrontations between male gods like Thor and serpentine adversaries, revealing a complex gender dimension to Norse serpent symbolism that scholars continue to investigate.

Legacy of Norse Serpent Mythology

The powerful serpent imagery from Norse mythology continues to influence contemporary culture, from literature and art to popular entertainment. Modern fantasy literature, from Tolkien’s dragons to the ice dragons in George R.R. Martin’s works, draws inspiration from Norse serpentine creatures. Viking-inspired jewelry featuring Jörmungandr remains popular among those interested in Norse heritage or aesthetic. Contemporary Heathen and Ásatrú religious movements have revived and reinterpreted ancient Norse serpent symbolism in their spiritual practices. The enduring fascination with these mythological serpents speaks to their psychological resonance as symbols of primordial power, cosmic boundaries, and the eternal cycle of creation and destruction that continues to captivate the human imagination across cultures and centuries.

Norse mythology presents a rich tapestry of serpent symbolism that transcends simplistic good-versus-evil narratives. From the world-encircling Jörmungandr to the gnawing Níðhöggr at Yggdrasil’s roots, snakes embodied cosmic forces fundamental to the Viking worldview. These serpentine beings represented both the destructive chaos that would ultimately lead to Ragnarök and the regenerative potential that would birth a new world from the old. Through archaeological evidence, surviving texts, and cultural practices, we can glimpse how these powerful serpent images shaped Viking understanding of life, death, and the mysterious forces governing their world. In a culture intimately connected to nature’s harsh realities, the snake’s dual nature as both dangerous predator and symbol of renewal made it an ideal vehicle for expressing complex cosmological concepts that continue to fascinate us today.