In the shadow of the great pyramids and along the fertile banks of the Nile, ancient Egyptians developed one of history’s most complex and enduring symbolic languages. Among their rich tapestry of sacred symbols, the snake emerged as a powerful emblem of rebirth, renewal, and eternal life. This seemingly paradoxical association—linking a creature often feared with the concept of regeneration—reveals profound insights into Egyptian spiritual beliefs and their intimate observation of the natural world. Their reverence for serpents transcended mere fascination, becoming deeply integrated into religious practices, artistic expressions, and even concepts of kingship. Through exploring this symbolic relationship, we gain a window into how ancient Egyptians interpreted the cyclical patterns of existence and their quest to understand life’s greatest mystery: the potential for renewal after death.

The Shedding Skin: Nature’s Perfect Metaphor

The foundation of the snake’s association with rebirth in Egyptian culture stemmed primarily from direct observation of its natural behavior. Egyptians were keen observers of the natural world, and the snake’s ability to shed its skin periodically presented a perfect, visible metaphor for renewal. When a snake sloughs off its old skin, it emerges looking refreshed and rejuvenated—a process that must have seemed magical to ancient observers. This regular shedding allows snakes to grow throughout their lives, dispense with parasites, and repair damaged scales, making them appear perpetually renewed. Egyptians interpreted this physical transformation as evidence that snakes possessed the secret to eternal renewal, viewing each shedding as a form of rebirth rather than merely a biological function. This biological reality formed the cornerstone upon which the symbolic significance of serpents was built in Egyptian religious thought.

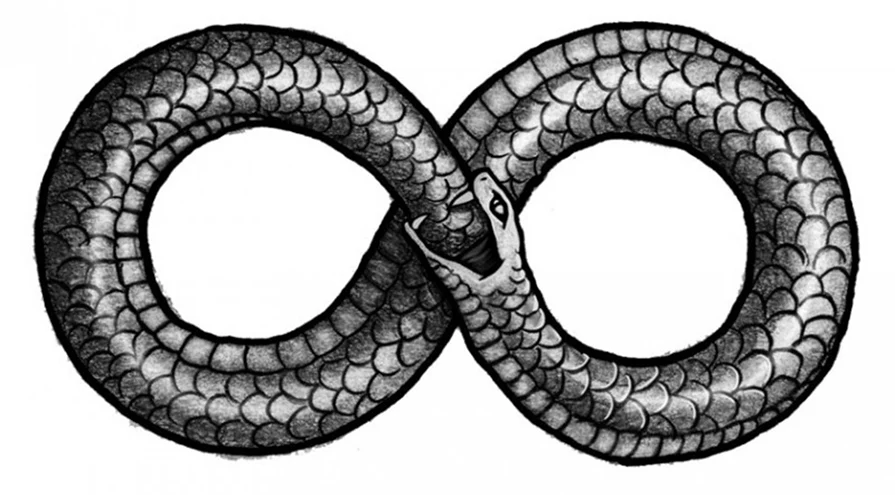

Ouroboros: The Self-Consuming Serpent

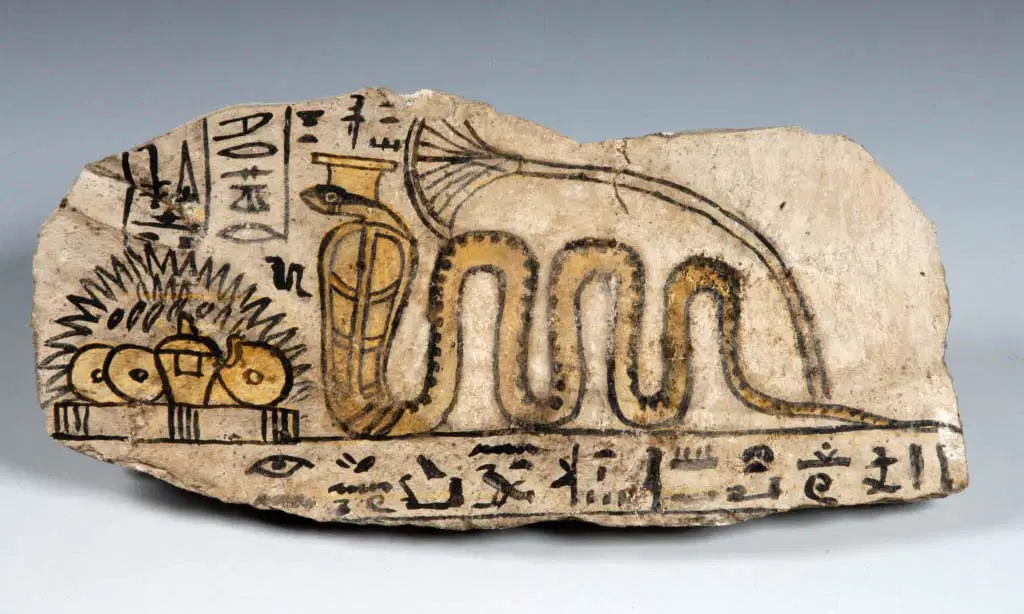

Among the most profound serpent symbols in Egyptian iconography was the ouroboros—a snake depicted consuming its tail. This circular representation embodied the cyclical nature of existence that was central to Egyptian cosmology. The ouroboros represented the unending cycle of creation and destruction, with no beginning and no end, mirroring the Egyptian conception of time as circular rather than linear. First appearing in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld in Tutankhamun’s tomb, this symbol would later influence Greek philosophy and Western alchemical traditions. For Egyptians, the self-consuming serpent represented not just rebirth but the eternal return of all things, suggesting that death was merely a transition rather than an endpoint. This powerful symbol reinforced their belief in the afterlife and the potential for spiritual regeneration after physical death.

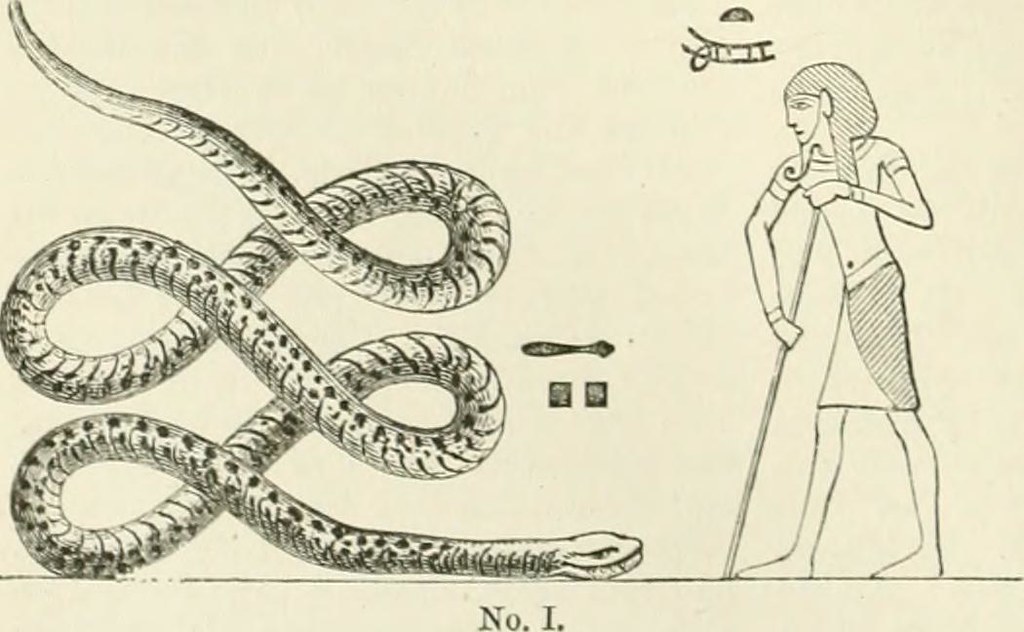

Apophis: The Chaos Serpent

Not all serpent symbolism in Egyptian culture was associated with positive renewal—the mighty chaos serpent Apophis (also called Apep) represented the destructive aspect of the rebirth cycle. Apophis was the great enemy of the sun god Ra, attempting to destroy him each night as Ra made his journey through the underworld. This eternal battle between order and chaos was seen as necessary for rebirth to occur, embodying the Egyptian understanding that destruction often precedes creation. In Egyptian funerary texts, priests and the deceased had to help defeat Apophis to ensure the sun’s rebirth each morning and the continuation of cosmic order. The defeat of Apophis each night allowed Ra to be reborn at dawn, creating a powerful metaphor for overcoming death itself. This mythological narrative demonstrates how Egyptians saw both creation and destruction as necessary parts of the rebirth process, with serpents playing central roles in both aspects.

Wadjet: The Protective Serpent Goddess

Among Egypt’s most important deities associated with serpents was Wadjet, the cobra goddess who served as protector of Lower Egypt and the pharaoh. Represented as a rearing cobra with spread hood, Wadjet appeared on the pharaoh’s crown as the uraeus—a powerful symbol of royal authority and divine protection. Beyond her protective aspects, Wadjet was intimately connected with concepts of rebirth through her association with the Eye of Ra, which had regenerative powers. Her fiery, protective nature was believed to destroy enemies while simultaneously ensuring the king’s rebirth in the afterlife. As one of Egypt’s oldest deities, dating to predynastic times, Wadjet’s evolution demonstrates how serpent symbolism was foundational to Egyptian religious thought rather than a later development. Her dual aspects of destruction and protection perfectly encapsulated the Egyptian understanding of how rebirth required both the ending of one state and the protective nurturing of a new beginning.

Serpents in Egyptian Creation Myths

Serpents played vital roles in various Egyptian creation myths, further cementing their association with primordial creation and rebirth. In the Hermopolitan creation tradition, eight primeval deities known as the Ogdoad took the form of frogs and serpents, representing the watery chaos from which creation emerged. These serpent deities were associated with the waters of Nun, the primordial ocean that existed before creation and to which everything would eventually return. In other traditions, the creator god Atum was sometimes depicted as a serpent returning to primordial waters after the world’s end, only to begin creation anew in an endless cycle. The presence of serpents at both the beginning and end of creation reinforced their connection to rebirth on a cosmic scale. These creation myths show how deeply embedded serpent symbolism was in Egyptian concepts of how existence perpetually renews itself through cycles of creation, destruction, and recreation.

The Royal Uraeus: Power and Resurrection

used as a symbol of sovereignty, royalty, deity, and divine authority in ancient Egypt.

Perhaps no serpent symbol was more visible in ancient Egyptian culture than the uraeus—the rearing cobra that adorned royal crowns and headpieces. More than just a symbol of protection, the uraeus represented the king’s ability to be reborn as a divine being after death. The fiery spitting cobra was thought to embody solar fire, connecting it to Ra’s regenerative journey and the pharaoh’s potential for rebirth. When depicted on royal funerary masks, like the famous golden mask of Tutankhamun, the uraeus symbolically facilitated the king’s transformation into an Osiris-like resurrected being. The position of the uraeus on the forehead also connected it to the Third Eye concept—the seat of enlightenment and spiritual transformation. As both destroyer and protector, the uraeus serpent perfectly embodied the Egyptian understanding that rebirth required both the fiery destruction of the old and divine protection for the emerging new form.

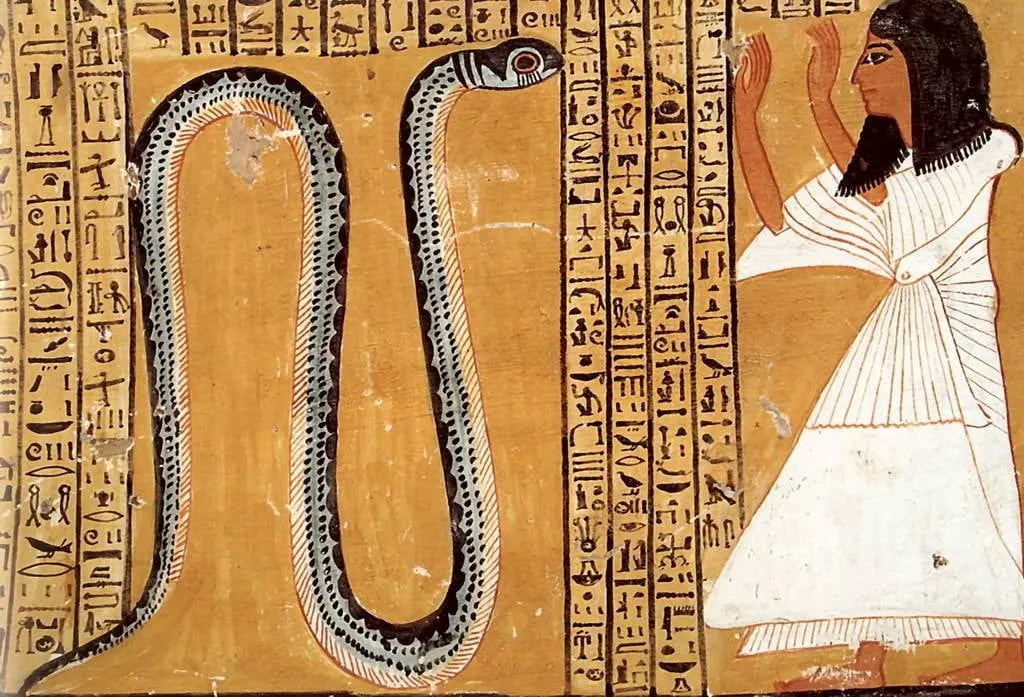

Serpents in Funerary Texts and Afterlife Beliefs

The Egyptian Book of the Dead and tomb walls throughout the Nile Valley featured numerous serpent images connected to rebirth and the afterlife journey. Many protective serpent deities guarded the gates of the underworld, requiring the deceased to know their names to pass safely through to rebirth. In the Amduat, which detailed Ra’s nightly journey, serpents both threatened and aided the sun god’s passage toward rebirth at dawn. Perhaps most telling was the depiction of mummified individuals with serpent imagery, suggesting the deceased would undergo a snake-like transformation and renewal. The “fiery serpent” mentioned in certain spells would help transform the deceased into a divine being, shedding their mortal limitations like a snake sheds its skin. These funerary associations demonstrate how deeply Egyptians connected serpent symbolism with the ultimate form of rebirth: resurrection after death.

Meretseger: The Peak’s Mistress

The serpent goddess Meretseger, whose name means “She Who Loves Silence,” was worshiped specifically by the craftsmen who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Associated with the pyramid-shaped mountain peak that overlooked the valley, Meretseger represented both the danger and protection associated with royal rebirth. Workers believed she could strike those who desecrated tombs with blindness or venomous bites, while simultaneously protecting those who respected the sacred spaces of transformation. Interestingly, Meretseger could grant forgiveness and healing to those who repented, suggesting a power of spiritual rebirth through moral transformation. Small shrines dedicated to her were established where workers could pray for her forgiveness and protection, showing how serpent veneration was integrated into daily life. Her dual nature—both punishing and healing—reflects how Egyptians saw serpents as embodying the necessary duality of the rebirth process: something had to end for something new to begin.

Nehebkau: The Cosmic Serpent of Unification

The primordial serpent god Nehebkau played a crucial role in Egyptian conceptions of rebirth through his function of uniting the ka (life force) with the ba (personality) after death. This unification created the akh, the transformed spiritual being that could achieve rebirth in the afterlife. Depicted as a serpent with human arms and legs, Nehebkau represented the mysterious transformative power that allowed separate components to be reunited in a new form. As “provider of attributes,” he helped the deceased reclaim their faculties and powers in the afterlife, essentially facilitating their rebirth as a complete being. His serpentine form emphasized his connection to the underworld and transformation processes. Nehebkau’s role demonstrates how Egyptians conceptualized rebirth not simply as a return to previous existence but as a transformative unification resulting in an enhanced spiritual state.

Serpent Amulets and Protective Magic

Ordinary Egyptians incorporated serpent symbolism into their daily lives through protective amulets and household items connected to concepts of rebirth and renewal. Cobra amulets were particularly popular, believed to transfer the protective and regenerative qualities of the serpent to the wearer. Pregnant women often wore snake-shaped jewelry to ensure safe delivery, itself seen as a form of rebirth as a new life emerged from within another. Snake-shaped wands were used in healing rituals, connecting serpent energy to physical rejuvenation and recovery from illness. The presence of these items in non-royal contexts demonstrates how serpent symbolism permeated all levels of Egyptian society, not just elite religious practice. These everyday objects show how deeply integrated the serpent-rebirth connection was in practical Egyptian thought, extending beyond abstract theology into personal protective practices.

Renenutet: The Nourishing Harvest Goddess

The cobra goddess Renenutet embodied the connection between serpents and agricultural renewal, further expanding the rebirth symbolism. As guardian of the harvest and granaries, Renenutet represented how snakes protected Egypt’s vital grain supply from rodents, connecting them to the annual cycle of agricultural rebirth. Her name derived from the word “renen,” meaning “to nurse” or “to rear,” and she was often depicted as a cobra nursing a child or with a woman’s head on a cobra’s body. During harvest festivals, Egyptians would make offerings to Renenutet to ensure future agricultural fertility and abundance, directly connecting serpent veneration to cyclical renewal. Her association with both destruction (of pests) and nourishment perfectly encapsulated the Egyptian understanding of how rebirth required both protective and nurturing aspects. This agricultural connection demonstrates how serpent-rebirth symbolism was grounded in practical observations of how snakes contributed to human survival.

Serpents and Sacred Knowledge

In Egyptian thought, serpents were frequently associated with secret knowledge and wisdom, particularly knowledge about rebirth and transformation. The sinuous movement of snakes, seeming to emerge from the earth itself, connected them to chthonic wisdom and hidden truths about life’s mysteries. Certain priests and magicians claimed special knowledge of snake magic that could facilitate transformation and healing, essentially controlling the power of rebirth. The serpent staff became a symbol of healing knowledge, influencing later Greek associations between snakes and medicine that persist today in the caduceus symbol. Egyptian magical texts included numerous spells involving serpents, particularly for protection during transitions (birth, death, illness) when rebirth energies were needed. This connection between serpents and sacred knowledge established a tradition that would influence many later mystical traditions in which snakes represent enlightenment and spiritual awakening.

The Living Legacy of Egyptian Serpent Symbolism

The Egyptian association between serpents and rebirth proved remarkably influential, spreading far beyond the borders of ancient Egypt to influence numerous other cultures and religious traditions. The ouroboros symbol was adopted by Greek alchemists and later European esoteric traditions as a powerful emblem of eternal return and spiritual transformation. Early Gnostic sects incorporated Egyptian serpent symbolism into their concepts of spiritual rebirth and enlightenment, sometimes reframing biblical serpent narratives through an Egyptian symbolic lens. Even modern psychological interpretations, particularly Carl Jung’s analysis of snake dreams as symbols of psychological renewal, owe a debt to Egyptian associations between serpents and rebirth. The medical caduceus, with its entwined serpents, traces its origins partly to Egyptian healing associations with snake symbolism. This enduring legacy demonstrates the psychological power and resonance of Egypt’s serpent-rebirth connection, which continues to influence how we symbolically represent transformation and renewal in contemporary culture.

Ancient Egyptians developed one of history’s most sophisticated symbolic systems, with the snake standing as perhaps their most complex and multifaceted emblem of regeneration. Through careful observation of serpent biology and behavior, they recognized powerful parallels to their spiritual aspirations for renewal and resurrection. From the cosmic ouroboros to the protective uraeus, from agricultural fertility goddesses to underworld gatekeepers, serpents slithered through every aspect of Egyptian concepts of rebirth. Their dual nature—both destructive and protective—perfectly embodied the Egyptian understanding that all renewal requires an ending before a new beginning. This symbolic association proved so compelling that it transcended ancient Egyptian civilization itself, continuing to influence how humans conceptualize transformation and rebirth across cultures and throughout history. In the sinuous form of the serpent, Egyptians found the perfect natural symbol for life’s most profound mystery: the possibility that from death might come renewal, and that existence might continue in cycles of eternal return.