The question of whether snakes can experience regret after striking at prey or perceived threats touches on fascinating aspects of reptilian cognition and emotion. While humans readily attribute emotions to animals with expressive faces and familiar behaviors, creatures like snakes present a more enigmatic case. Their alien appearance and seemingly cold demeanor make it difficult for us to interpret their mental states. Yet behind those unblinking eyes and flicking tongues lies a complex nervous system that guides behaviors essential for survival. This exploration delves into what science can tell us about snake cognition, how their brains process information, and whether these remarkable reptiles might experience something akin to what we call regret.

Understanding Snake Cognition

Snake cognition differs dramatically from human thought processes due to fundamental differences in brain structure. The reptilian brain lacks a neocortex, the brain region in mammals associated with higher-order cognitive functions including conscious thought and emotional processing. Instead, snakes possess an enlarged forebrain structure called the dorsal ventricular ridge that handles many sensory integration tasks. Research indicates that while snakes can learn from experience and form basic associations, they likely process information in ways quite different from mammals. Their cognition appears primarily oriented toward immediate survival needs rather than complex emotional assessment or reflection on past actions.

The Biology of Snake Strikes

Snake strikes represent one of nature’s most perfectly optimized hunting mechanisms, fine-tuned through millions of years of evolution. When a snake strikes, it typically responds to a complex interplay of sensory inputs including thermal detection (in pit vipers), visual movement detection, and chemical cues detected by their vomeronasal organ. Many strikes occur at extraordinary speeds—some vipers can launch from coiled positions to targets in under 50 milliseconds, faster than a human can blink. The strike itself is largely governed by instinctual patterns and reflexive responses rather than conscious deliberation. This reflexive nature suggests that snakes don’t “decide” to strike in the same contemplative way humans make choices.

Emotions in Reptiles: What We Know

The scientific understanding of reptilian emotions remains limited, with researchers still debating the extent to which reptiles experience subjective feelings. Most scientists agree reptiles can experience primary emotional states like fear, aggression, and pleasure tied to survival and reproduction. These basic states help motivate behaviors essential for survival such as fleeing from threats, defending territory, or seeking mates. However, secondary emotions like guilt, shame, or regret require more complex cognitive abilities including self-awareness and mental time-travel capabilities. Current evidence suggests reptiles likely lack the neural architecture necessary for these sophisticated emotional experiences, though our understanding continues to evolve as research methods improve.

Learning From Mistakes: Snake Behavior Modification

While snakes may not experience regret as humans understand it, they can certainly learn from past experiences and modify their behavior accordingly. Captive snakes quickly learn feeding routines and can associate certain stimuli with food rewards or negative consequences. Wild snakes demonstrate remarkable behavioral plasticity, adjusting hunting strategies based on success rates and environmental conditions. For example, rattlesnakes that strike and miss prey will often adjust their approach on subsequent attempts, modifying strike distance or timing. This adaptive learning represents a form of experience-based behavior modification that helps snakes survive, even without conscious reflection on past failures.

The Neurological Basis of Regret

Regret as humans experience it involves complex neurological processes centered in the prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and hippocampus—brain regions associated with decision-making, counterfactual thinking, and memory integration. These structures work together to allow us to imagine alternative outcomes to our actions and emotionally process the gap between what happened and what could have been. Snake brains lack these specialized structures in the form mammals possess them. Their brain organization prioritizes sensory processing and instinctual response patterns rather than abstract thinking about past actions. This fundamental neurological difference suggests that snakes almost certainly cannot experience regret in the rich, reflective way humans do.

Mistaken Strikes and Predatory Behavior

Snakes occasionally strike at non-prey items or miss their intended targets, which might appear as “mistakes” from a human perspective. These misdirected strikes typically occur when the snake receives conflicting or misleading sensory information. For instance, a snake might strike at a moving stick that triggers its motion-detection systems in a way similar to prey. After such mistaken strikes, snakes typically reset their hunting behavior rather than displaying behaviors that might indicate frustration or disappointment. They simply return to their alert posture and continue scanning for legitimate prey opportunities. This matter-of-fact response to missed strikes suggests their behavior is governed more by instinctual programming than emotional assessment.

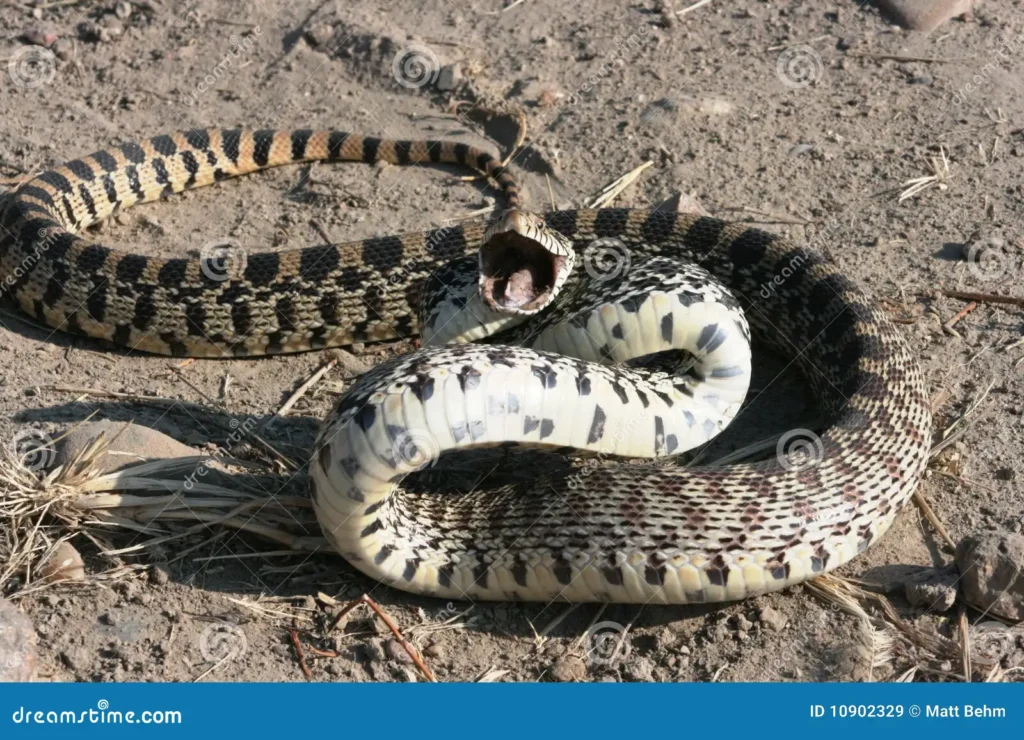

Defensive Strikes vs. Predatory Strikes

Snakes employ strikes for both hunting and self-defense, with notable differences between these two behaviors. Predatory strikes are typically precise, measured actions aimed at securing prey, often followed by immediate constriction or venom injection. Defensive strikes, by contrast, tend to be faster, less targeted, and frequently involve less committed forward motion—many are actually “warning” strikes not intended to make contact. Following defensive strikes, snakes commonly retreat rather than pursue, suggesting their primary goal was creating distance from a perceived threat. Neither type of strike appears to involve post-action assessment that would indicate regret, though snakes may adjust future defensive responses based on whether their strategy succeeded in deterring the threat.

Anthropomorphism and Its Limitations

Humans naturally tend to project human emotions and thought processes onto animals, a cognitive tendency known as anthropomorphism. This tendency becomes particularly problematic when interpreting the behaviors of animals like snakes whose evolutionary lineage diverged from mammals over 300 million years ago. Their alien body plan, lack of facial expressions, and fundamentally different sensory world make accurate interpretations of their mental states especially challenging. While anthropomorphism can sometimes be a useful starting point for generating hypotheses about animal behavior, scientific investigation requires more rigorous approaches. Careful behavioral studies, comparative neurobiology, and evolutionary context provide more reliable insights into snake cognition than intuitive human projections.

Conservation Implications of Snake Cognition

Understanding snake cognition has important implications for conservation efforts targeting these often misunderstood reptiles. Snakes face numerous threats worldwide including habitat destruction, road mortality, and deliberate killing due to fear and misunderstanding. Recognizing the cognitive capacities snakes possess—including spatial learning, recognition of familiar environments, and sensory adaptations—can inform more effective conservation strategies. For example, knowledge about how snakes learn to navigate their habitats might improve corridor design between fragmented habitats. While snakes may not experience regret or other complex emotions, acknowledging their remarkable adaptive intelligence can foster a greater human appreciation for these essential predators in ecosystem functioning.

Cultural Perspectives on Snake Behavior

Human interpretations of snake behavior vary dramatically across cultures, influencing how we conceptualize their mental capabilities. In many Western traditions, snakes are portrayed as calculating, cunning creatures capable of malicious intent—from the biblical serpent in Eden to countless villainous representations in literature and film. Conversely, many Eastern and indigenous traditions view snakes as wise, powerful beings deserving of respect and sometimes veneration. These cultural narratives inevitably color scientific inquiry and public perception regarding snake cognition. Understanding these cultural biases helps researchers maintain objectivity when investigating actual snake mental capabilities, separating cultural projections from biological reality.

Comparative Cognition: Snakes vs. Other Animals

Placing snake cognition in the broader context of animal intelligence reveals both limitations and specialized adaptations. While snakes lack the problem-solving abilities of corvids (crows and ravens) or the social intelligence of elephants and primates, they excel in other domains. Their chemosensory processing allows them to create detailed mental maps of their environment based on chemical cues imperceptible to humans. Some species demonstrate impressive spatial memory, returning to specific hibernation dens across vast distances year after year. Research with captive snakes has revealed capabilities for recognizing individual human handlers and distinguishing between familiar and unfamiliar environments. These specialized cognitive adaptations highlight how intelligence evolves to meet specific ecological challenges rather than advancing along a single scale of increasing complexity.

Future Research Directions

The frontier of snake cognition research offers exciting possibilities for a deeper understanding of these enigmatic creatures. Advances in non-invasive neural imaging might eventually allow researchers to observe snake brain activity during decision-making processes, providing direct evidence of cognitive processing. Innovative experimental designs could test for more complex learning capabilities, including potential evidence of behavioral flexibility that might indicate more sophisticated decision-making than currently recognized. Comparative studies across different snake species could reveal how cognitive capabilities vary with ecological niche and evolutionary history. Additionally, long-term observational studies of wild snakes using modern tracking technologies might uncover behavioral patterns suggesting more complex cognitive processes than laboratory studies can detect.

While current scientific evidence strongly suggests snakes cannot experience regret as humans understand it, this doesn’t diminish the fascinating complexity of snake cognition. These ancient reptiles navigate their world through sensory systems and neural processing uniquely adapted to their ecological niches and evolutionary history. Their intelligence manifests not in human-like emotions or abstract thinking, but in exquisitely refined instincts, remarkable sensory integration, and adaptable learning that has allowed them to thrive for over 100 million years. Rather than asking if snakes experience human-like emotions, perhaps the more interesting question is appreciating the alien intelligence they do possess—one shaped by evolutionary pressures vastly different from those that molded our own minds. In this perspective, snakes don’t need to regret their strikes to be worthy of our scientific curiosity and conservation efforts.