In the fascinating world of reptiles, non-venomous snakes face a challenging existence. Without the benefit of venom to defend themselves, these remarkable creatures have evolved an impressive array of alternative strategies to survive encounters with larger, stronger, and often more aggressive predators. From physical adaptations to behavioral tactics, these serpents demonstrate nature’s ingenuity in the endless evolutionary arms race. Their success stories are testament to the power of adaptation and the principle that brains can triumph over brawn in the animal kingdom. This exploration of non-venomous snake defenses reveals sophisticated survival mechanisms that have developed over millions of years, allowing these seemingly vulnerable animals to thrive despite their position in the middle of the food chain.

Mimicking Venomous Counterparts

Perhaps one of the most ingenious defensive strategies employed by non-venomous snakes is Batesian mimicry—the evolutionary development of visual similarities to dangerous venomous species. The harmless milk snake, with its vibrant red, black, and yellow bands, bears a striking resemblance to the deadly coral snake, prompting potential predators to think twice before attacking. Similarly, the non-venomous scarlet kingsnake has evolved coloration patterns nearly identical to those of the eastern coral snake, effectively “borrowing” the reputation of its venomous lookalike. This mimicry extends beyond mere coloration, with some species even adopting the distinctive body postures and defensive behaviors of their venomous counterparts. For predators, the risk of mistakenly attacking a potentially deadly snake outweighs the nutritional benefit, making mimicry an extremely effective survival tactic that requires no actual fighting ability.

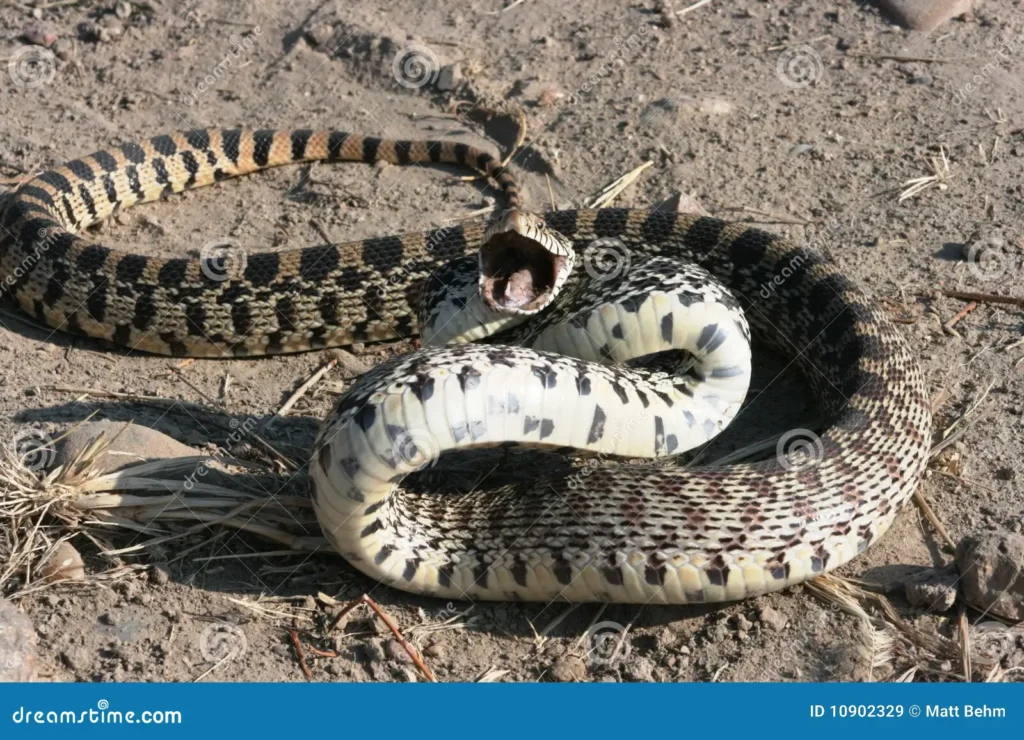

Death-Feigning Behaviors

When confronted by a predator that’s determined to make them a meal, several non-venomous snake species employ a dramatic last-resort tactic—playing dead. The hognose snake delivers one of the most convincing performances in the animal kingdom, rolling onto its back, opening its mouth, letting its tongue loll out, and even emitting a foul-smelling musk to complete the illusion of death. This behavior, known as thanatosis, exploits the fact that many predators prefer live prey and will lose interest in what appears to be a decomposing snake. What makes this strategy particularly effective is the snake’s commitment to the act—a hognose can remain in its death pose for minutes or even hours if necessary. If disturbed during this performance, the snake will immediately “die” again, showing remarkable dedication to maintaining the deception until the threat has passed completely.

Rapid Escape Mechanisms

Speed and agility serve as primary defense mechanisms for many non-venomous snakes when confronted with danger. Species like the black racer can move at impressive speeds of up to 8-10 mph across open ground, using their streamlined bodies and powerful muscles to quickly distance themselves from threats. Water snakes demonstrate remarkable aquatic mobility, capable of darting beneath the surface and navigating underwater with precision to escape terrestrial predators. The specialized scales on a snake’s belly, called ventral scutes, function like treads on a tire, gripping surfaces and allowing for efficient propulsion even on challenging terrain. For arboreal species such as the green tree python, their exceptional climbing abilities enable them to retreat to higher branches where many ground-based predators cannot follow, turning the three-dimensional forest environment into a complex escape route.

Camouflage and Cryptic Coloration

Many non-venomous snakes have evolved body patterns and colors that blend seamlessly with their preferred habitats, making them nearly invisible to both predators and prey. The kenyan sand boa, with its sandy-colored scales and speckled pattern, disappears against the desert substrate where it lives. In forest environments, species like the emerald tree boa display vibrant green coloration that matches the surrounding foliage, while their irregular pattern of lighter markings mimics dappled sunlight filtering through leaves. Beyond mere coloration, many snakes possess textured scales that break up their outline and disrupt the visual perception of their body shape. This cryptic advantage works so effectively that predators can pass within inches of a perfectly still camouflaged snake without detecting its presence, demonstrating how evolution has perfected this passive defense strategy over millions of years.

Intimidating Defensive Displays

When flight isn’t an option, many non-venomous snakes resort to elaborate bluffing displays designed to make predators reconsider their attack. The common kingsnake will vibrate its tail rapidly against dry leaves, creating a rattling sound remarkably similar to that of a rattlesnake, despite having no rattle. Rat snakes and pine snakes can flatten their heads to appear more triangular and viper-like, while simultaneously hissing loudly and striking repeatedly with closed mouths. The Indian sand boa takes intimidation further by hiding its head and raising its thicker tail, which resembles a head, potentially confusing predators about which end to attack. These displays work because they create doubt in the predator’s mind about the potential risk, and in nature, where injuries can be fatal, many predators will opt to seek easier prey rather than risk being bitten by what appears to be a dangerous snake.

Defensive Regurgitation Tactics

Some non-venomous snakes employ a particularly unpleasant defensive strategy when cornered—regurgitating their most recent meal. This response serves multiple purposes in the snake’s survival toolkit. First, it lightens the snake’s body weight, potentially improving its escape capabilities if an opportunity arises. Second, the sight and smell of partially digested prey can distract or repel predators sensitive to such stimuli. Third, the regurgitated material creates a diversion that might draw the predator’s attention away from the snake itself. For species like the grass snake, this tactic is often combined with the release of a foul-smelling musk from specialized glands, creating a truly revolting sensory experience for would-be predators. This multisensory defensive approach proves highly effective against mammalian predators with sensitive noses, such as foxes and coyotes, who may abandon the hunt entirely rather than deal with such an unappetizing encounter.

Muscle Contraction and Body Inflation

When threatened, many non-venomous snakes alter their physical appearance through controlled muscle manipulations that make them appear larger and more intimidating. The eastern hognose snake can flatten its neck and upper body to nearly three times its normal width, creating a cobra-like hood that suggests venomous capabilities. Puff adders inflate their bodies by filling their lungs with air, increasing their apparent size significantly while simultaneously producing a loud, intimidating hiss. Some species, like certain pythons, can tense their muscles in waves that ripple visibly beneath their scales, creating an impression of greater strength and vitality. These physical transformations exploit the natural caution of predators when confronting unfamiliar or apparently dangerous prey, effectively manipulating risk assessment calculations in the predator’s brain without requiring the snake to actually engage in combat.

Nocturnal Activity Patterns

Many non-venomous snake species have evolved to be primarily active during nighttime hours, significantly reducing their exposure to diurnal visual predators like hawks, eagles, and many mammals. Under the cover of darkness, snakes like the night snake and western ground snake can hunt and travel with reduced risk, using specialized sensory adaptations such as heat-sensing pits or enhanced olfactory capabilities to navigate and locate prey. Their dark, often muted coloration serves as effective camouflage against the night landscape, further reducing detection risk. This temporal niche separation represents an elegant evolutionary solution to predation pressure, essentially allowing snakes to operate in a different “time zone” than many of their most dangerous predators. For species that must occasionally be active during daylight hours, this nocturnal adaptation is complemented by extremely cautious behavior during the day, including a greater tendency to remain hidden under rocks, logs, or in burrows until darkness returns.

Social Mobbing Behaviors

Though snakes are generally thought of as solitary creatures, certain non-venomous species demonstrate remarkable cooperative defensive behaviors when threatened by predators. Garter snakes, particularly when gathered at communal hibernation sites called hibernacula, will sometimes respond collectively to threats. When disturbed, multiple snakes may simultaneously release musk, creating a powerful deterrent effect that would be less effective from a single individual. In some documented cases, groups of water snakes basking together will all slide into water almost simultaneously when threatened, creating confusion for predators attempting to target a single individual. Young snakes of some species have been observed clustering together for protection, making it more difficult for predators to isolate a single target. These social defensive strategies, while not as elaborate as those seen in herd mammals or flocking birds, nonetheless represent an intriguing adaptation that leverages safety in numbers for creatures not typically considered social.

Specialized Scale Adaptations

The seemingly simple scales covering a non-venomous snake’s body actually represent sophisticated defensive technology developed over millions of years of evolution. In many species, dorsal scales overlap like roof shingles, creating a tough, flexible armor that can resist punctures and tears from predator attacks. The rough scales of species like the saw-scaled snake create significant friction against a predator’s grip, making the snake difficult to hold onto and providing precious seconds for escape. Some species possess keeled scales with ridges that not only strengthen the scale structure but can also collect dirt and debris, enhancing camouflage in natural environments. Perhaps most impressively, the scales of many colubrids (the largest family of non-venomous snakes) are designed to break away relatively easily from the underlying skin when grabbed, allowing the snake to slip free while leaving the predator with nothing but a mouthful of scales—a perfect example of a sacrificial defense mechanism that prioritizes survival over temporary injury.

Coiling and Striking Bluffs

When cornered, many non-venomous snakes adopt an aggressive defensive posture characterized by tight body coiling and theatrical striking displays. The bull snake demonstrates this behavior with remarkable commitment, coiling its body, elevating its head, hissing loudly, and lunging forward in convincing strikes that rarely make contact. Gopher snakes take this display further by vibrating their tails, inflating their bodies, flattening their heads, and striking repeatedly with such conviction that they are frequently mistaken for rattlesnakes by humans and predators alike. What makes these bluffs particularly effective is their integration of multiple sensory cues—visual (the striking motion), auditory (the hissing or tail rattling), and kinesthetic (the perceived threat of impact)—creating a multidimensional threat display. For predators, the potential cost of misjudging such a display could be a venomous bite, making the evolutionary math straightforward: it’s safer to back down than to test whether the snake is bluffing.

Cloacal Discharge Defense Mechanisms

When physically handled or cornered by predators, many non-venomous snakes employ a particularly unpleasant last-resort defense mechanism—releasing foul-smelling waste and musk from their cloaca. The common garter snake is notorious for this defensive tactic, producing a substance so pungent that it can linger on a predator’s fur or a human handler’s skin for days despite washing. This malodorous defense works through multiple pathways: it creates immediate disgust in the predator, potentially causing it to drop the snake; it marks the predator with a scent that can make it more detectable to its own predators; and it can create a learned aversion that prevents future predation attempts. Snake musk contains complex chemical compounds specifically evolved to target mammalian olfactory sensitivities, making it particularly effective against common predators like foxes, coyotes, and domestic cats. This chemical defense requires minimal energy expenditure compared to physical fighting and can be deployed even when the snake is firmly in a predator’s grasp, making it an efficient last-chance survival mechanism.

Utilizing Environmental Refuges

Non-venomous snakes demonstrate remarkable awareness of their surroundings, habitually mapping and utilizing environmental features that can serve as instant refuges when predators approach. Species like the eastern indigo snake maintain mental maps of multiple burrows within their territory, rarely venturing too far from these safety zones when hunting or basking. Aquatic species such as water snakes position themselves strategically near the water’s edge, allowing for instant submersion when aerial predators are spotted. Tree-dwelling species like the green snake have evolved to recognize the densest foliage areas that provide optimal concealment, often retreating to these specific locations when threatened. Perhaps most impressively, many desert-dwelling snakes have developed the ability to “swim” beneath loose sand when threatened, disappearing from sight within seconds and leaving predators with no visible target. This strategic use of the environment represents a sophisticated cognitive adaptation that complements the snake’s physical defenses, effectively turning the landscape itself into a protective ally.

In the eternal evolutionary chess match between predator and prey, non-venomous snakes stand as masterful strategists, compensating for their lack of venom with an impressive diversity of alternative survival tactics. From sophisticated mimicry to convincing death performances, from lightning-fast escapes to chemical warfare, these reptiles have developed a comprehensive defensive toolkit that allows them to thrive in environments filled with larger, stronger potential predators. Their success reminds us that in nature, survival often depends more on adaptability and specialized traits than on brute strength or offensive capabilities. As we continue to study these remarkable creatures, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for their evolutionary ingenuity but also potential insights into novel defense mechanisms that might inspire human technologies and problem-solving approaches. The non-venomous snake, often maligned or overlooked, deserves recognition as one of nature’s great survivors—a testament to the power of evolutionary adaptation in the face of seemingly overwhelming challenges.