For most of their lives, snakes slither through their environments as solitary hunters, avoiding interaction with their own kind. Unlike many animals that thrive in social groups, these remarkable reptiles have evolved to embrace a life of isolation—with one fascinating seasonal exception. During breeding season, snakes temporarily abandon their solitary ways, engaging in complex mating behaviors that contrast dramatically with their usual independent existence. This intriguing paradox of snake behavior reveals the delicate balance between evolutionary advantages of solitude and the biological imperative to reproduce. Let’s explore why snakes prefer to live alone and what changes during that special season when they seek each other out.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Solitude

Snakes have evolved over millions of years to become highly specialized predators that generally benefit from a solitary lifestyle. This solitary nature allows them to be more effective hunters, as they don’t have to share their food resources with others of their kind. When a snake captures prey, it consumes the entire animal, often taking days or even weeks to digest larger meals completely. Having evolved without the need to coordinate hunting strategies with others, snakes have developed highly refined individual hunting techniques that work best when operating alone. Additionally, their slow metabolism means they eat relatively infrequently compared to mammals, making group living unnecessary and potentially disadvantageous from a survival perspective.

Resource Competition Among Snakes

Living alone helps snakes avoid competing with members of their own species for limited resources in their environment. Food, water, and suitable shelter are often scarce and unpredictably distributed in many snake habitats. When multiple snakes inhabit the same territory, they must divide these precious resources, potentially leading to nutritional stress or dangerous confrontations. Small rodents and other prey animals that make up most snake diets aren’t typically abundant enough in one area to support multiple predators with similar dietary needs. This resource competition becomes especially problematic in harsh environments or during seasonal food shortages, further reinforcing the evolutionary advantage of solitary living in these reptiles.

Territorial Behavior in Snake Species

Many snake species exhibit territorial behaviors that discourage close proximity to other snakes outside of breeding season. While not all snakes actively defend territories in the traditional sense, they often maintain home ranges where they conduct their daily activities with minimal overlap with conspecifics. Some species, particularly certain vipers and pythons, will display aggressive behaviors toward intruding snakes, including threat displays, hissing, or even physical combat. These territorial instincts help snakes secure access to optimal hunting grounds, basking spots, and hibernation sites without interference. Even in species that don’t actively defend territories, individuals typically avoid one another’s scent trails, naturally creating a spaced distribution across the landscape.

Predator Avoidance Through Isolation

Solitary living provides snakes with significant advantages when it comes to avoiding predators in their environment. A single snake creates less disturbance, leaves fewer scent trails, and attracts less attention than a group would, making detection by predators less likely. Many snake species have evolved remarkable camouflage that works best when they remain still and alone, blending perfectly into their surroundings. When snakes gather in groups, they become more conspicuous to predators like hawks, eagles, large mammals, and even other snakes. Additionally, solitary snakes can quickly retreat into hiding places that might not accommodate multiple individuals, allowing for more efficient escape strategies when threats approach.

The Energy Conservation Principle

Snakes are ectothermic animals that rely on external heat sources to regulate their body temperature, making energy conservation a crucial aspect of their survival strategy. Solitary living aligns perfectly with this biological imperative, as it allows snakes to minimize unnecessary movement and energy expenditure that would otherwise be required for social interaction. A lone snake can remain motionless for extended periods, conserving precious energy while waiting for prey to approach or digesting a recent meal. Social behaviors would demand additional energy expenditure that simply isn’t justifiable from a survival perspective for these energy-efficient predators. This energy conservation principle is particularly important for snakes in temperate regions, where they must carefully manage their resources to survive lengthy hibernation periods.

Communication Limitations in Snakes

Unlike highly social animals that have evolved sophisticated communication systems, snakes have relatively limited means of communicating with one another, which naturally predisposes them toward solitary living. Snakes lack the vocal capabilities found in many social species and primarily rely on chemical cues and physical displays for the limited communication they do engage in. Their vision is generally adapted for detecting movement rather than recognizing complex social signals or facial expressions. These communication limitations make complex social interactions challenging and energetically costly, further reinforcing the evolutionary path toward solitude. While some species can detect vibrations and have limited visual communication through body positioning, these mechanisms pale in comparison to the rich communication systems found in social animals.

The Remarkable Exception: Breeding Season

Despite their predominantly solitary nature, snakes undergo a dramatic behavioral shift during breeding season when the biological imperative to reproduce temporarily overrides their preference for solitude. During this time, male snakes will actively seek out females, sometimes traveling considerable distances and engaging in behaviors entirely unlike their normal routines. Breeding aggregations can form in some species, with multiple males competing for access to receptive females through elaborate combat rituals or competitive mating strategies. These seasonal gatherings represent the only regular social interaction many snake species will experience throughout their lives. The hormonal changes that trigger this behavioural shift are powerful enough to temporarily suspend the instinctual avoidance behaviours that normally keep snakes apart.

Chemical Signals During Mating Season

During breeding season, female snakes release powerful pheromones that male snakes can detect from remarkable distances, triggering the temporary suspension of their solitary nature. These chemical signals create invisible scent trails that males follow using their highly specialized vomeronasal organs, also known as Jacobson’s organs. A male snake will flick his forked tongue to collect these airborne particles, then press it against the roof of his mouth where the vomeronasal organ analyzes the chemical information. This sophisticated chemical communication system allows snakes to find potential mates with astonishing precision, even in complex environments where visual detection would be nearly impossible. Once a male locates a receptive female, his entire behavioral pattern shifts from avoidance to persistent courtship, demonstrating the powerful influence of these seasonal pheromones.

Complex Mating Rituals

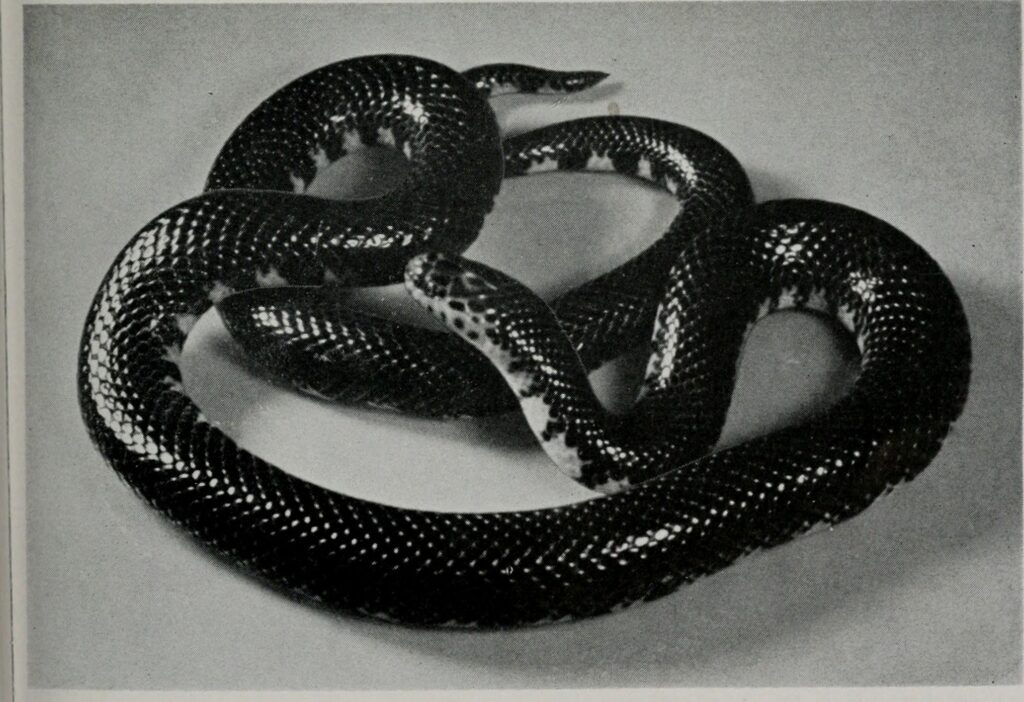

When snakes do come together during breeding season, they engage in complex courtship and mating behaviors that temporarily transform these normally solitary creatures into socially engaged animals. Male garter snakes may participate in “mating balls,” where dozens or even hundreds of males simultaneously court a single female in a writhing mass of intertwined bodies. Certain species engage in elaborate courtship dances, with males performing rhythmic body undulations or head-bobbing displays to attract female attention. Some male snakes, particularly certain vipers and rattlesnakes, engage in “combat dances” where they wrestle to establish dominance and earn mating rights with nearby females. These intricate social interactions represent a complete departure from their standard solitary behavior patterns and occur exclusively during the brief breeding period.

Seasonal Aggregations for Hibernation

In addition to breeding season, some snake species in colder climates form temporary aggregations during winter hibernation, creating another exception to their solitary lifestyle. These hibernation dens, known as hibernacula, may contain dozens or even hundreds of snakes sharing the same protected space to survive freezing temperatures. Garter snakes are particularly known for this behavior, sometimes forming massive aggregations in frost-free underground cavities or rocky crevices. These winter gatherings serve a purely practical purpose—accessing limited suitable hibernation sites—rather than representing true social behavior. Interestingly, these same hibernation sites often become breeding grounds when snakes emerge in spring, as the concentration of individuals creates immediate mating opportunities before they disperse back into their solitary lives.

Maternal Care in Select Species

While most snake species abandon their eggs or young immediately after birth, returning to their solitary existence, some species exhibit remarkable exceptions to this pattern through various forms of maternal care. Certain pythons, like the ball python, will coil around their eggs for weeks, maintaining optimal incubation temperatures and protecting them from predators. King cobras construct elaborate nests and guard their eggs until hatching, displaying a level of parental investment rare among reptiles. Some vipers and rattlesnakes are viviparous (giving live birth) and may temporarily shelter their newborns near their bodies for protection during their most vulnerable hours. These maternal behaviors represent another fascinating exception to the typically solitary nature of snakes, though they are generally brief compared to the parental care seen in mammals or birds.

Evolutionary Explanations for Solitary Behavior

The predominantly solitary nature of snakes can be traced back to their evolutionary history and ecological niche as specialized reptilian predators. Unlike mammals that often evolved social structures for cooperative hunting, predator defence, or offspring care, snakes developed along a different evolutionary path that favoured individual survival strategies. Their elongated body plan, limbless locomotion, and specialized feeding adaptations all evolved in ways that function optimally in a solitary context. The ancestors of modern snakes likely faced selection pressures that rewarded solitary hunting and ambush predation rather than group living. This evolutionary trajectory has been reinforced over millions of years, resulting in the predominantly solitary lifestyle we observe in most snake species today, with only the necessary exceptions for reproduction and, in some cases, winter survival.

The Balance Between Solitude and Reproduction

The contrast between snakes’ year-round solitude and their brief periods of intense social interaction during breeding season highlights the delicate evolutionary balance between individual survival and species continuation. This balance represents a fascinating example of how natural selection can shape behavior to maximize both individual fitness and reproductive success. Snakes have evolved to take advantage of the benefits of solitary living—reduced competition, efficient hunting, predator avoidance, and energy conservation—while still ensuring genetic diversity through their seasonal breeding gatherings. This specialized behavioral adaptation allows snakes to thrive in diverse habitats around the world, from deserts to rainforests, demonstrating the success of their unique approach to balancing solitude with necessary social interaction. The temporary nature of their social gatherings minimizes the costs associated with group living while still fulfilling the essential function of reproduction.

In conclusion, the solitary nature of snakes represents a highly successful evolutionary strategy that has allowed these remarkable reptiles to thrive for millions of years. Their preference for solitude offers numerous advantages, including efficient hunting, reduced competition, predator avoidance, and energy conservation. Yet the biological imperative to reproduce creates a fascinating seasonal exception when snakes temporarily abandon their solitary ways to engage in complex mating behaviors. This delicate balance between solitude and occasional sociality demonstrates the remarkable adaptability of these animals and the diverse ways in which natural selection shapes behavior. By understanding why snakes choose to live alone—except during one crucial season—we gain deeper insight into the complex interplay between evolutionary pressures and behavioral adaptations in the natural world.