In the complex dance of predator and prey, snakes occupy a fascinating middle ground. While they’re skilled hunters in their own right, these legless reptiles must also evade numerous predators including birds of prey, larger mammals, and even other reptiles. Despite lacking limbs and often being outmatched in size, snakes have evolved remarkable strategies to outsmart those who would make them a meal. Their survival doesn’t always depend on brute strength or speed, but rather on cleverness, deception, and evolutionary adaptations that have been refined over millions of years. Let’s explore seven remarkable instances where these slithering survivors have demonstrated their exceptional ability to outwit their would-be killers, showcasing nature’s endless capacity for ingenious defensive strategies.

Playing Dead: The Ultimate Deception

Perhaps the most dramatic example of snake deception is the death feigning behavior most famously demonstrated by the North American hognose snake. When threatened, these remarkable reptiles will flip onto their backs, open their mouths, let their tongues hang out, and even release a foul-smelling musk to complete the illusion of death. This act isn’t merely superficial—they commit fully to the performance, sometimes remaining “dead” for minutes or even hours until the threat has passed. The strategy exploits the fact that many predators, particularly birds and mammals, prefer fresh kills and will abandon prey that appears to be already deceased. Even when physically manipulated or moved, a dedicated hognose snake will flop lifelessly back onto its back, refusing to break character until safety is assured.

Rattlesnake Warning Systems: Preemptive Defense

Rattlesnakes have evolved one of the most recognizable warning systems in the animal kingdom—the eponymous rattle that serves as a sophisticated predator deterrent. This adaptation, composed of interlocking keratin segments, creates a distinctive buzzing sound when vibrated rapidly, often reaching frequencies of 60 vibrations per second. Rather than attempting to flee or fight immediately, rattlesnakes use this acoustic warning to prevent confrontations altogether, essentially outsmarting predators before an attack even begins. The genius of this strategy lies in its energy efficiency—instead of expending valuable calories in escape or combat, the snake leverages sound to create a psychological barrier. Research has shown that many predators, including coyotes, hawks, and badgers, recognize and avoid this warning, having learned through evolution or experience to associate the sound with danger.

Masters of Camouflage: Hiding in Plain Sight

Many snake species have elevated camouflage to an art form, with coloration and patterns so precisely matched to their environments that they become virtually invisible. The Gaboon viper of Africa exemplifies this strategy with its intricate pattern of geometric shapes that perfectly mimic the forest floor’s dappled light and leaf litter. Similarly, the vine snake possesses an elongated body and green coloration that allows it to disappear among branches and foliage. This camouflage isn’t static—some species can actually adjust their coloration over time to better match seasonal changes in their environment. The effectiveness of this strategy lies in its passive nature; predators simply cannot attack what they cannot perceive, allowing snakes to conserve energy while avoiding detection entirely.

Venomous Spitting: Keeping Predators at a Distance

Certain cobra species have developed the remarkable ability to project their venom significant distances with astonishing accuracy, targeting the eyes of potential predators. This adaptation allows these snakes to defend themselves without engaging in close-quarters combat where their size disadvantage might prove fatal. African spitting cobras can launch their venom up to eight feet away, creating an effective buffer zone around themselves. The venom itself is specifically adapted to cause intense pain and temporary blindness rather than lethality, functioning more as a deterrent than a killing mechanism. This sophisticated defense system demonstrates evolutionary problem-solving at its finest—these snakes have essentially developed a ranged weapon that incapacitates threats without requiring direct contact.

Tail Distraction: The Sacrificial Strategy

Many snake species employ a clever tactical deception by drawing attention to their tails rather than their more vulnerable heads. Species like the rubber boa actually use their blunt tails as decoys, waving them to mimic their heads while keeping their actual heads safely tucked away. When attacked, they may even tolerate minor damage to their tails, which can heal, rather than risking fatal head injuries. This strategy reaches its evolutionary peak in species with specialized tail tips, such as the spider-tailed horned viper of Iran, which possesses a tail modified to look remarkably like a moving spider—attracting not just the attention of predators but also luring in prey. The willingness to sacrifice a non-vital body part represents a sophisticated cost-benefit analysis hardwired into these animals’ defensive repertoire.

Defensive Regurgitation: The Unexpected Escape

When caught in the grip of a predator, some snake species resort to a particularly unappetizing escape tactic—they regurgitate their recent meals. This strategy serves multiple purposes with remarkable efficiency. First, it immediately reduces the snake’s weight, making escape more feasible by increasing mobility. Second, the sudden appearance of partially digested prey often startles the predator, creating a crucial moment of confusion that the snake can exploit. Third, the regurgitated matter itself can serve as a distraction, giving the predator an alternative food source to focus on while the snake makes its getaway. Finally, the strong smell of the regurgitated meal can mask the snake’s own scent trail, making it harder for the predator to track it once it has escaped.

Kinked Posturing: The Intimidation Display

Many non-venomous snakes have developed elaborate bluffing displays that convincingly mimic the posture and behavior of their more dangerous relatives. The harmless hognose snake, when threatened, will flatten its neck into a convincing cobra-like hood, hiss loudly, and strike repeatedly—though usually with a closed mouth. Similarly, certain kingsnake species adopt the distinctive kinked S-shaped striking pose of venomous vipers despite lacking venom themselves. This mimicry exploits predators’ innate or learned aversion to dangerous snake species, creating a protective psychological barrier. The effectiveness of this strategy lies in its cognitive manipulation—the predator makes a risk assessment based on false information and chooses to avoid conflict rather than call the snake’s bluff.

Synchronized Defense: Strength in Numbers

Certain snake species, particularly garter snakes in northern climates, have developed social defensive strategies that showcase unexpected complexity for supposedly solitary creatures. During winter hibernation, these snakes gather in communal dens called hibernacula, sometimes containing thousands of individuals. When emerging in spring, they remain in large aggregations that confuse and overwhelm potential predators. When threatened, the mass of intertwined snakes creates a disorienting visual and olfactory environment that makes it difficult for predators to target any single individual. This social defense strategy effectively distributes the risk across the entire group, dramatically reducing the chances of any particular snake being captured. Research has shown that predation rates on individual garter snakes are significantly lower when they’re part of these large springtime aggregations.

Vibrational Sensitivity: Early Warning System

Snakes possess an extraordinary sensitivity to ground vibrations that functions as an early warning system against approaching predators. This adaptation is particularly important for species that lack limbs to rapidly escape or climb. Their entire body, in contact with the substrate, essentially functions as a giant seismic detector that can perceive minute disturbances created by predator movements from considerable distances. This vibration detection is so refined that many species can distinguish between the movements of potential predators and non-threatening animals or environmental factors like wind. The advance notice provided by this sensory adaptation gives snakes critical time to retreat to burrows, climb vegetation, or prepare defensive displays before the predator even has visual contact. Some species have specialized scales on their undersides that enhance this sensitivity even further, functioning almost like specialized organs dedicated to vibration detection.

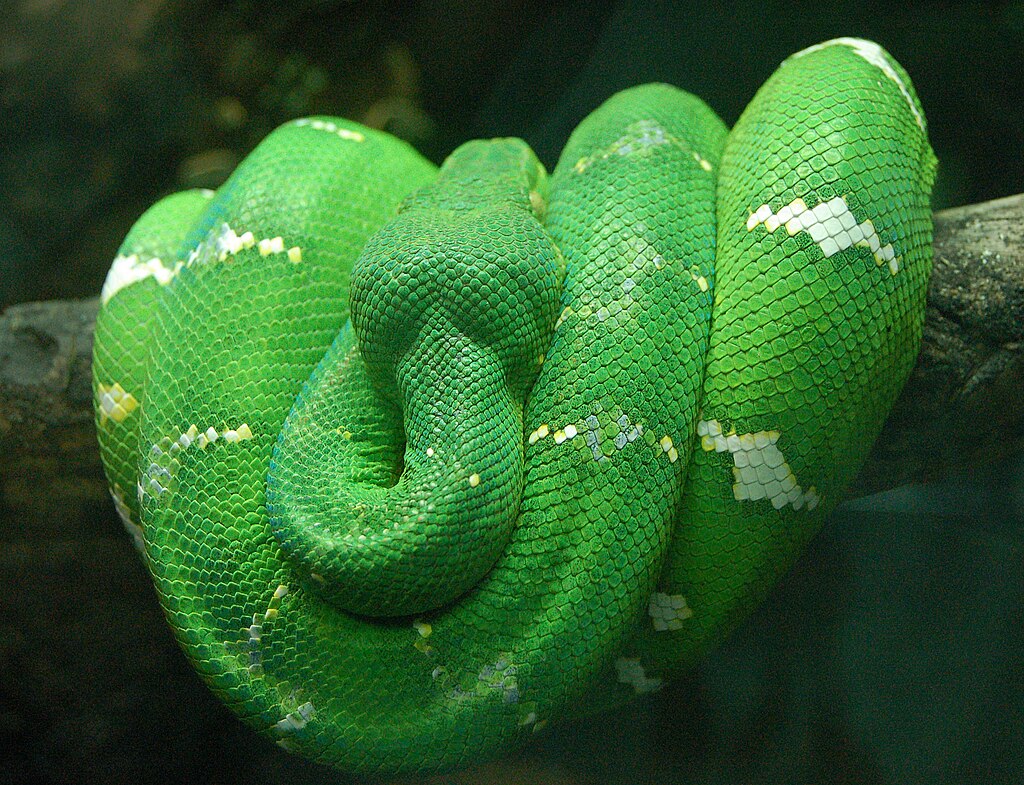

Thermal Deception: Outsmarting Infrared Predators

Pit vipers and pythons face a particular challenge in evading mammalian predators equipped with infrared sensing abilities. In a fascinating evolutionary arms race, some snake species have developed the ability to regulate their surface temperature to minimize their thermal signature when threatened. By controlling blood flow to their skin, these snakes can temporarily reduce the temperature differential between their bodies and the surrounding environment, essentially becoming “thermally invisible” to heat-sensing predators like certain mammals. This sophisticated physiological response requires minimal energy expenditure while providing significant protection. For arboreal species, this adaptation is particularly valuable as it allows them to remain motionless among branches without betraying their presence through heat emissions.

Chemical Warfare: Secreting Deterrents

Beyond the well-known venom used for hunting and defense, many snake species produce additional chemical compounds specifically designed to deter predators without causing harm. Garter snakes and water snakes can release a complex mixture of musky compounds from specialized glands when handled or threatened, creating an odor so unpleasant that predators often immediately release them. These secretions often contain compounds that trigger disgust or aversion reactions in mammals through evolutionary adaptations. The effectiveness of this strategy is enhanced by its persistence—the chemicals can remain on the predator’s mouth or paws, creating a lasting negative association that prevents future attack attempts. Some evidence suggests these compounds may even temporarily deaden taste receptors, making the predator unable to taste its food properly for a short period after exposure.

Behavioral Flexibility: Adapting to New Threats

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of snake defense is not any single adaptation but rather their remarkable behavioral flexibility when facing novel predators. Research has documented rapid changes in defensive behaviors when snake populations encounter introduced predators not present in their evolutionary history. For example, island snake species that evolved without mammalian predators have been observed developing new defensive responses within just a few generations when exposed to introduced rats or mongoose. This rapid adaptability extends to individual learning as well, with studies showing that snakes can modify their defensive tactics based on previous encounters and their outcomes. This cognitive and behavioral plasticity represents a form of real-time problem solving that allows snakes to outsmart even predators they haven’t co-evolved with over millennia.

Conclusion: Nature’s Defensive Masterclass

The remarkable defensive strategies employed by snakes represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement, showcasing nature’s ingenuity in the eternal struggle for survival. From sophisticated chemical signals to elaborate behavioral deceptions, these adaptations demonstrate that outsmarting predators often proves more effective than outrunning or outfighting them. What makes these strategies particularly fascinating is how they compensate for the apparent vulnerabilities of the snake’s body plan—lacking limbs, these reptiles have evolved alternative solutions that turn their constraints into unique advantages. As we continue to study these remarkable creatures, we gain not just insight into their survival techniques, but also a deeper appreciation for the complex and ingenious ways that evolution shapes defensive adaptations throughout the natural world.