Throughout human history, serpent deities have slithered their way into the religious iconography of civilizations across the globe. These powerful snake-headed gods and goddesses represented various aspects of life, death, fertility, wisdom, and the cosmos. Archaeological discoveries have unearthed remarkable artifacts depicting these serpentine deities, providing windows into ancient belief systems and mythological narratives. From Mesoamerica to Egypt, from the Indus Valley to ancient Greece, snake-headed divinities have commanded reverence and inspired awe in countless cultures. This article explores six fascinating ancient artifacts that feature these enigmatic snake-headed gods, offering insights into their symbolic significance and the civilizations that venerated them.

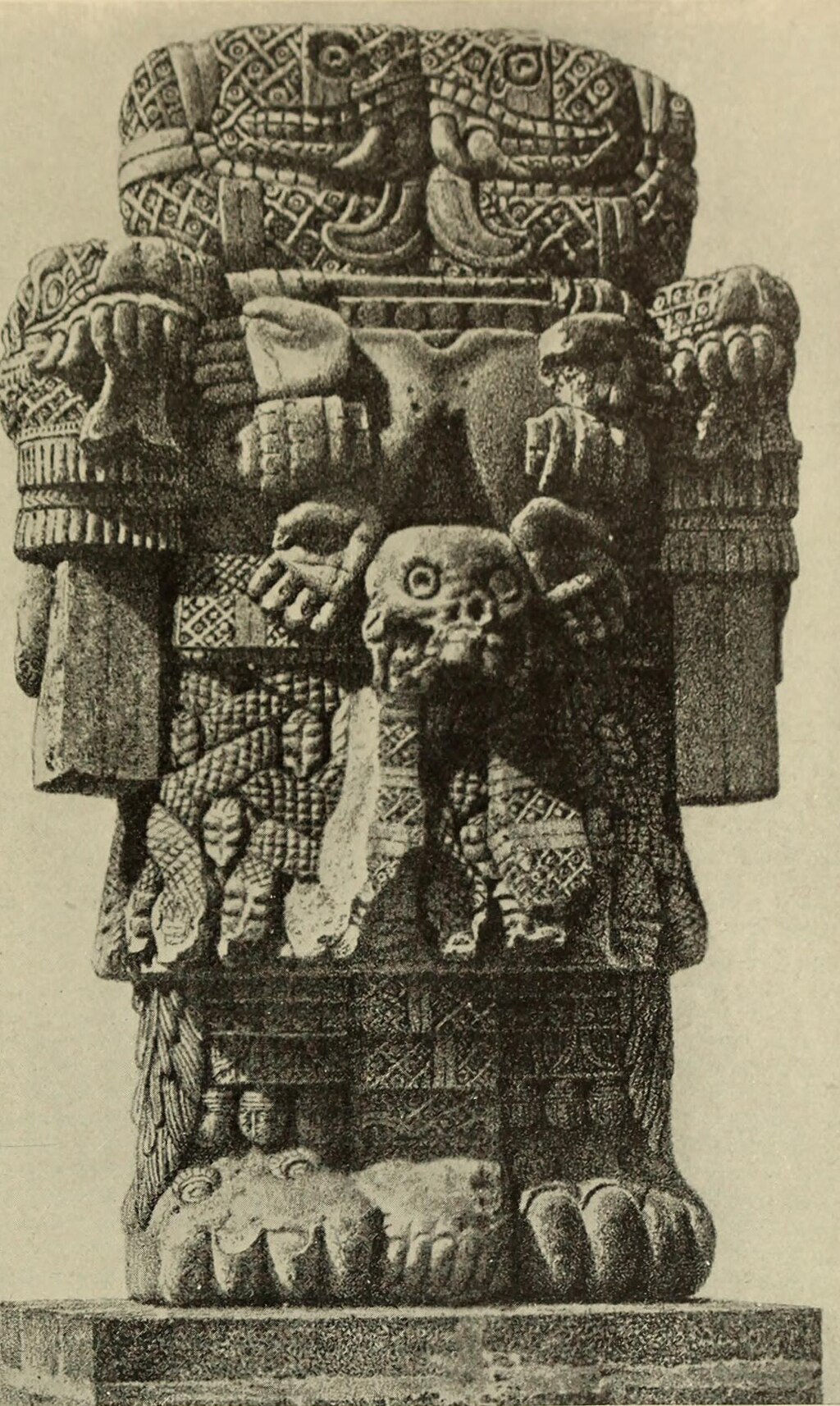

The Aztec Coatlicue Statue: Mexico’s Serpent-Skirted Mother Goddess

The monumental stone statue of Coatlicue, discovered beneath Mexico City’s central plaza in 1790, stands as one of the most terrifying and impressive representations of a snake deity in pre-Columbian art. Standing nearly 8.5 feet tall and carved from a single basalt block, this fearsome sculpture depicts the Aztec goddess whose name translates to “Snake Skirt.” Though not entirely snake-headed, Coatlicue features twin serpent heads that emerge from her severed neck, creating a horrifying visage that embodies her dual nature as creator and destroyer. Her skirt consists of intertwined serpents, and her necklace displays severed human hearts and hands, representing her insatiable hunger for sacrifice. This remarkable artifact, dated to the late 15th century, symbolizes the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth that was central to Aztec cosmology and remains one of the most significant examples of serpent deity iconography in world art.

The Wadjet Amulets of Ancient Egypt: Protective Cobra Goddess

Among the most ubiquitous and significant snake deities in ancient world iconography is Wadjet, the protective cobra goddess of Lower Egypt. Archaeological excavations have yielded countless amulets depicting this powerful serpent deity, who was believed to spit fire at the pharaoh’s enemies and guard the rulers of Egypt. Particularly striking are the gold and lapis lazuli Wadjet amulets discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb, dating to approximately 1323 BCE. These exquisite artifacts typically feature a rearing cobra with expanded hood, sometimes crowned with the Red Crown of Lower Egypt, embodying royal protection and divine authority. Wadjet’s image also appeared prominently on the pharaoh’s brow as the uraeus symbol, a protective cobra that became one of the most recognizable elements of royal regalia. These portable protective charms were worn by royalty and commoners alike, demonstrating how deeply ingrained serpent worship was in Egyptian religious practice across social classes.

The Naga Sculptures of Angkor Wat: Cambodia’s Divine Serpents

The magnificent temple complex of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, constructed in the early 12th century CE, features some of the most impressive snake deity representations in Southeast Asian religious art. The causeway leading to the main temple is flanked by massive stone balustrades carved to represent multi-headed nagas, divine serpents from Hindu-Buddhist mythology. These impressive sculptures depict Vasuki and other mythological serpent deities with between five and seven cobra heads splayed in a fan-like formation, creating an awe-inspiring entrance to the sacred space. Inside the temple complex, intricate bas-reliefs show the famous myth of the Churning of the Ocean of Milk, where devas (gods) and asuras (demons) use the body of the naga king Vasuki as a cosmic rope to extract the elixir of immortality. The artistic detail in these serpent representations is remarkable, with scales, facial features, and ornate crowns meticulously rendered in stone, demonstrating the central importance of naga worship in Khmer religious tradition and cosmology.

The Feathered Serpent Columns of Teotihuacan: Quetzalcoatl’s Ancient Domain

The ancient city of Teotihuacan in central Mexico, which flourished between 100 BCE and 550 CE, houses some of the most impressive architectural representations of a snake deity in pre-Columbian America. The Temple of the Feathered Serpent features massive stone heads of Quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent god, protruding from ornately carved platforms. These sculptural elements, dating to around 200-250 CE, depict the deity with an unmistakable serpent head adorned with elaborate feathered crests, representing the god’s dual nature as creature of both earth and sky. Archaeological evidence suggests these imposing sculptural elements were once painted in vibrant colors, with red highlighting the serpent’s fanged mouth and blue-green emphasizing the feathered elements. The sheer scale and prominence of these representations in the city’s ceremonial center indicates the central importance of this snake deity to Teotihuacan’s religious and political life, predating similar iconography in later Mesoamerican civilizations like the Toltec and Aztec cultures that would also venerate the feathered serpent.

The Serpent Staffs of Ningishzida: Mesopotamia’s Divine Guardian

Among the oldest representations of snake-headed gods come from ancient Mesopotamia, where the deity Ningishzida was depicted as a serpent-headed guardian of the underworld. Particularly noteworthy is the famous Libation Vase of Gudea, dated to approximately 2100 BCE during the Neo-Sumerian period. This remarkable chlorite vessel, discovered in the ancient city of Girsu (modern-day Tello in Iraq), features two intertwined serpents rising behind a seated figure, forming the caduceus-like emblem of Ningishzida. The serpents display distinctly rendered heads with clear ophidian features, representing the god’s primary manifestation. Additional artifacts including cylinder seals and relief carvings show Ningishzida in anthropomorphic form with serpents emerging from his shoulders, creating a hybrid deity that bridges human and serpentine realms. These representations are particularly significant as they demonstrate that snake deity worship existed in some of humanity’s earliest complex civilizations, suggesting the profound ancient roots of serpent symbolism in religious iconography across multiple continents.

The Gorgon Pediment of Corfu: Medusa’s Terrifying Visage

One of the most striking ancient European representations of a snake-headed deity comes from the western pediment of the Temple of Artemis in Corfu, Greece, dating to approximately 580 BCE. This massive limestone sculpture, over 9 feet tall, depicts the gorgon Medusa, a chthonic female monster with snakes for hair, who could turn onlookers to stone with her gaze. Unlike later classical representations that humanized Medusa, this archaic sculpture shows her with a broad grimacing face, protruding tongue, and a head writhing with individually carved serpents replacing her hair. The sculptural program includes her children, Pegasus and Chrysaor, emerging from her severed neck, embodying the Greek mythological concept of death giving rise to new life. This imposing temple decoration represents one of the earliest surviving examples of monumental Greek temple sculpture and reveals how snake-headed entities were positioned prominently in Greek religious architecture to ward off evil and protect sacred spaces.

The Symbolism Behind Snake-Headed Deities in Ancient Cultures

The prevalence of snake-headed gods across disparate ancient civilizations raises fascinating questions about the universal appeal of serpent symbolism in religious iconography. Snakes’ ability to shed their skin made them powerful symbols of regeneration, immortality, and cyclical time in many cultures, explaining their association with creator deities and underworld guardians. Their venomous nature connected them to both healing and death, making them appropriate emblems for deities who controlled life’s most critical transitions. In agricultural societies, snakes’ emergence from the earth linked them to fertility and the cyclical nature of harvests, while their silent, seemingly unpredictable movements associated them with prophetic knowledge and hidden wisdom. The dual nature of serpents—both protective and dangerous—mirrored ancient perspectives on divine powers that could both nurture and destroy, reflecting the complex relationship between humanity and the supernatural forces believed to control cosmic order.

Scientific Analysis and Dating of Snake God Artifacts

Modern archaeological techniques have revolutionized our understanding of ancient snake deity artifacts, providing crucial insights into their creation, use, and cultural context. Radiocarbon dating, when applicable to organic materials associated with these artifacts, has helped establish more precise chronologies for serpent worship across civilizations. Petrographic analysis of stone sculptures has revealed the quarry sources and transportation methods used to create monumental snake deity representations, shedding light on the economic and political resources dedicated to their production. Spectrographic analysis of pigments remaining on sculptures like the Quetzalcoatl representations at Teotihuacan has revealed the vibrant original colors that would have made these serpent deities even more impressive to ancient worshippers. DNA analysis of sacrificial remains associated with some snake deity temples, particularly in Mesoamerica, provides insights into the practices and rituals dedicated to these powerful supernatural entities, completing our picture of how these impressive artifacts functioned within their original religious contexts.

The Role of Snake Deities in Creation Myths

Across numerous ancient cultures, snake-headed gods frequently played pivotal roles in creation narratives, often embodying primordial chaos from which ordered existence emerged. In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr, the World Serpent, encircled the entire world, representing the boundaries of creation and the cosmic cycle. Egyptian cosmology featured Apep (or Apophis), the great serpent of chaos who constantly threatened to undo creation, battling nightly with the sun god Ra—a conflict depicted on numerous temple walls and papyri. In Hindu traditions represented in artifacts from India and Southeast Asia, the cosmic serpent Ananta (or Shesha) formed the resting couch for Vishnu between cycles of creation, symbolizing the eternal, infinite nature of the cosmos. These serpentine creation entities, captured in artistic representations across continents, reveal a remarkable cross-cultural pattern: the serpent as a symbol of both primordial chaos and creative potential, a dualistic nature that made snake deities particularly powerful figures in explaining how ordered existence emerged from cosmic disorder.

Snake Goddesses and Feminine Divine Power

While many snake deities across cultures were male, several of the most powerful and enduring serpent divinities were female, revealing important aspects of how ancient societies conceptualized feminine divine power. The Minoan Snake Goddess figurines from Crete (c. 1600 BCE), though not depicting goddess with snake heads but rather with serpents wrapped around their arms, demonstrate the early association between female deities and serpent power in Mediterranean cultures. The Aztec Coatlicue represents perhaps the most fearsome female serpent deity, embodying the terrifying aspects of maternal power that both creates and destroys. In Southeast Asian traditions, female naga deities like Manasa (the snake goddess of fertility and poison) held tremendous power over life, death, and healing, appearing in numerous sculptural representations across the region. These female snake deities often connected to aspects of fertility, protection, and dangerous transformative power, suggesting that serpent symbolism provided ancient cultures with a powerful visual vocabulary for expressing the more mysterious and feared aspects of feminine divine power that transcended simplistic categorization.

Ritual Uses of Snake Deity Artifacts

Archaeological contexts reveal that artifacts depicting snake-headed gods served various ritual functions beyond mere representation, actively participating in ancient religious practices. Excavations at temple sites across Mesoamerica have uncovered evidence that blood offerings were made directly onto snake deity sculptures, with specially designed channels and basins to collect sacrificial liquids, activating the stone representations through ritual feeding. In Egyptian contexts, Wadjet amulets were commonly included in mummification processes, placed directly on the body to extend divine protection into the afterlife journey. Temple inventories from Mesopotamia reveal that some serpent deity statues received regular offerings of food, drink, and clothing, treated as embodiments of the god rather than mere symbols. Evidence of wear patterns on some portable snake deity figures suggests they were regularly handled as part of divination practices, particularly in Greco-Roman contexts where serpents connected to oracular powers.

The Evolution of Snake Deity Representation Through History

The artistic portrayal of snake-headed gods underwent significant evolution over time, reflecting changing theological concepts and artistic conventions. Early Neolithic representations, such as those found at Çatalhöyük in Turkey (7500-5700 BCE), show rudimentary serpent imagery associated with fertility and rebirth but lack the sophisticated anthropomorphic hybridization seen in later periods. By the Bronze Age, cultures in Mesopotamia and Egypt had developed complex iconographies with standardized ways of depicting their serpent deities, with Egypt’s cobra goddess Wadjet appearing with remarkably consistent features across thousands of artifacts. Classical Greek representations show a fascinating transformation in how snake-headed beings like Medusa were depicted, evolving from monstrous early forms to increasingly humanized and even beautiful representations by the Hellenistic period. This artistic evolution reflects not just changing aesthetic preferences but deeper shifts in how these cultures related to the dangerous but necessary powers that snake deities represented, gradually domesticating and rationalizing forces that earlier generations had approached with greater awe and terror.

Contemporary Legacy of Ancient Snake Gods

The powerful imagery of ancient snake-headed deities continues to resonate in contemporary culture, art, and religious practice. Modern Hindu and Buddhist traditions in Southeast Asia still actively venerate naga deities, with new temple sculptures and paintings continuing artistic traditions thousands of years old. Indigenous communities in Mexico and Central America maintain spiritual connections to serpent deities like Quetzalcoatl, incorporating these ancient symbols into contemporary religious practices and cultural identity. In Western popular culture, ancient snake deities have influenced countless books, films, and video games, though often with significant reinterpretation that distances them from their original religious contexts. Museum exhibitions featuring these impressive artifacts attract millions of visitors worldwide, demonstrating the continuing fascination these ancient serpent representations hold for modern audiences. Though removed from their original contexts of worship, these snake-headed gods continue to captivate the human imagination, connecting us to our ancestors’ attempts to understand and visualize the mysterious powers governing life, death, and cosmic order.

The remarkable diversity of snake-headed deity artifacts across ancient civilizations speaks to a profound human tendency to associate serpents with divine power, wisdom, and cosmic forces. From the feathered serpent of Mesoamerica to the nagas of Southeast Asia, from the protective cobra goddesses of Egypt to the terrifying gorgons of Greece, these representations reflect both cultural specificity and cross-cultural patterns in religious symbolism. The six artifacts explored in this article represent merely a fraction of the rich archaeological evidence for serpent worship across human history. As modern scholarship continues to uncover and interpret these fascinating objects, we gain deeper insight into how our ancestors conceptualized divine power and its relationship to the natural world. The enduring presence of these serpentine deities across millennia of human religious art testifies to the snake’s unique power as a symbol capable of embodying the most profound mysteries of existence.