Throughout human history, snakes have slithered their way into the spiritual consciousness of civilizations across the globe. These serpentine creatures, with their ability to shed their skin and emerge renewed, have become powerful symbols of rebirth, transformation, and cyclical existence in numerous religious traditions. From ancient Mesopotamia to modern Hinduism, from indigenous American beliefs to African spiritual systems, the snake’s symbolic connection to renewal transcends geographical boundaries and time periods. This remarkable convergence of snake symbolism across disparate cultures reveals something profound about how humans observe and interpret the natural world. In this exploration, we’ll uncover why snakes have become such a universal emblem of rebirth and regeneration in religious systems worldwide.

The Biological Basis: Snake Shedding as Renewal

The primary biological feature that connects snakes to concepts of rebirth is their dramatic process of ecdysis, or skin shedding. Unlike mammals who continuously shed small amounts of skin, snakes periodically shed their entire outer layer in one piece, emerging with a fresh, vibrant exterior. This visible transformation occurs several times throughout a snake’s life, creating a perfect natural metaphor for rebirth and renewal. The shedding process itself appears almost magical to observers – the snake essentially crawls out of its old self, leaving behind a ghost-like impression of its former body. Ancient peoples witnessing this phenomenon naturally drew parallels to concepts of spiritual transformation, death, and resurrection. The fact that the snake emerges looking rejuvenated and often more vibrant in color only strengthened this symbolic connection to rebirth across cultures.

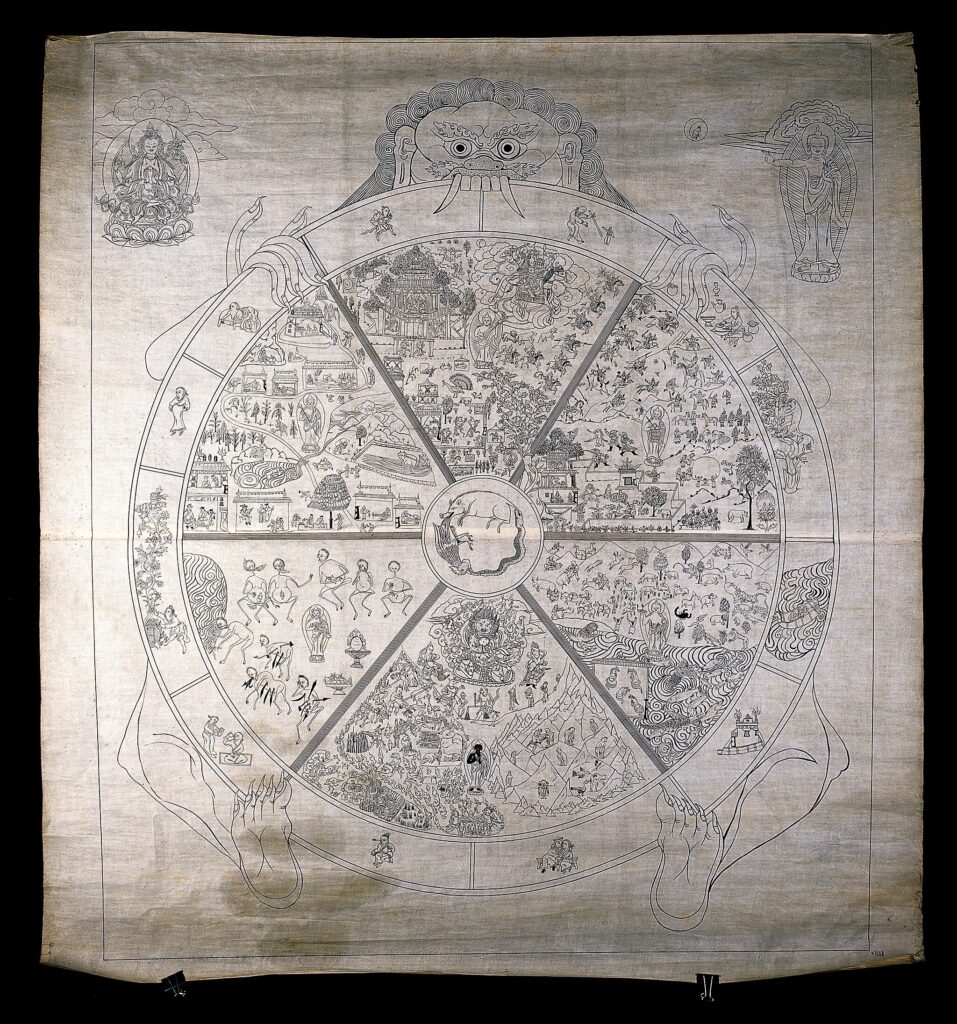

Ancient Egypt: The Ouroboros and Eternal Return

In Ancient Egyptian mythology, the symbol of the Ouroboros – a snake eating its own tail – represented the eternal cycle of destruction and recreation. This powerful symbol depicted a serpent forming a perfect circle, simultaneously consuming and regenerating itself in an endless loop. The Egyptians associated this serpentine imagery with the daily rebirth of the sun god Ra, who died each evening only to be reborn at dawn. Egyptian texts also connected snakes to the primordial waters of Nun, from which all life emerged at creation. The goddess Wadjet, often depicted as a cobra, served as a protective deity of Lower Egypt and was believed to control life-giving forces. Through these various incarnations, snakes became inseparable from Egyptian concepts of cyclical time, cosmic renewal, and the eternal return of all things.

Hinduism: Kundalini and Spiritual Awakening

In Hindu tradition, the concept of Kundalini represents one of the most direct connections between snakes and spiritual rebirth. Kundalini is visualized as a coiled serpent sleeping at the base of the spine, and through yogic practice, this dormant energy awakens and rises through the chakras, ultimately leading to spiritual enlightenment. This serpentine energy, when awakened, is said to bring about a complete spiritual rebirth and transformation of consciousness. Lord Shiva, one of Hinduism’s principal deities, is frequently depicted wearing snakes around his neck, symbolizing his mastery over death and cyclical existence. Additionally, the cosmic serpent Shesha (or Ananta) serves as the resting place for Lord Vishnu during intervals between universal creation cycles, directly connecting serpent symbolism to the Hindu concept of cosmic rebirth and recreation. The serpent’s connection to vital life energy and spiritual awakening makes it central to Hindu concepts of transformation and renewal.

Mesoamerican Beliefs: Quetzalcoatl and Creation

Among Mesoamerican civilizations, particularly the Aztecs and Maya, the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl (or Kukulkan) embodied profound concepts of rebirth and cosmic renewal. This divine serpent was associated with the creation of humanity, the gift of agriculture, and the cycles of Venus as morning and evening star. The Aztec calendar itself was built around cyclical time, with serpents often marking transitional points between cosmic ages or “suns.” Quetzalcoatl’s mythological death and rebirth narratives reflected the cyclical nature of creation itself, with the serpent symbolizing the bridge between death and new life. Temple architecture throughout Mesoamerica often incorporated serpent imagery, with the famous equinox shadow at Chichen Itza creating the illusion of a serpent descending the pyramid – a dramatic representation of divine energy moving between celestial and earthly realms. The feathered serpent thus connected heaven and earth while embodying the perpetual cycles of cosmic death and rebirth.

Biblical Traditions: From Fall to Resurrection

In Biblical traditions, the serpent presents a complex and often contradictory symbol related to death, rebirth, and transformation. While the Garden of Eden serpent is portrayed as a deceptive agent leading to humanity’s fall, other Biblical serpent imagery carries more positive associations with healing and resurrection. In the Book of Numbers, Moses creates a bronze serpent on a pole that heals those who look upon it – a symbol later referenced by Jesus in the New Testament as foreshadowing his own crucifixion and resurrection. Early Christian Gnostic traditions even interpreted the Eden serpent as a wisdom-bringer who initiated human spiritual awakening and self-knowledge. The Gospel of John explicitly connects the bronze serpent with Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, stating, “Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up.” This ambivalent position of serpents in Judeo-Christian tradition – simultaneously symbolizing both fall and salvation – reflects the complex nature of rebirth itself, which often requires a form of death or suffering as its precondition.

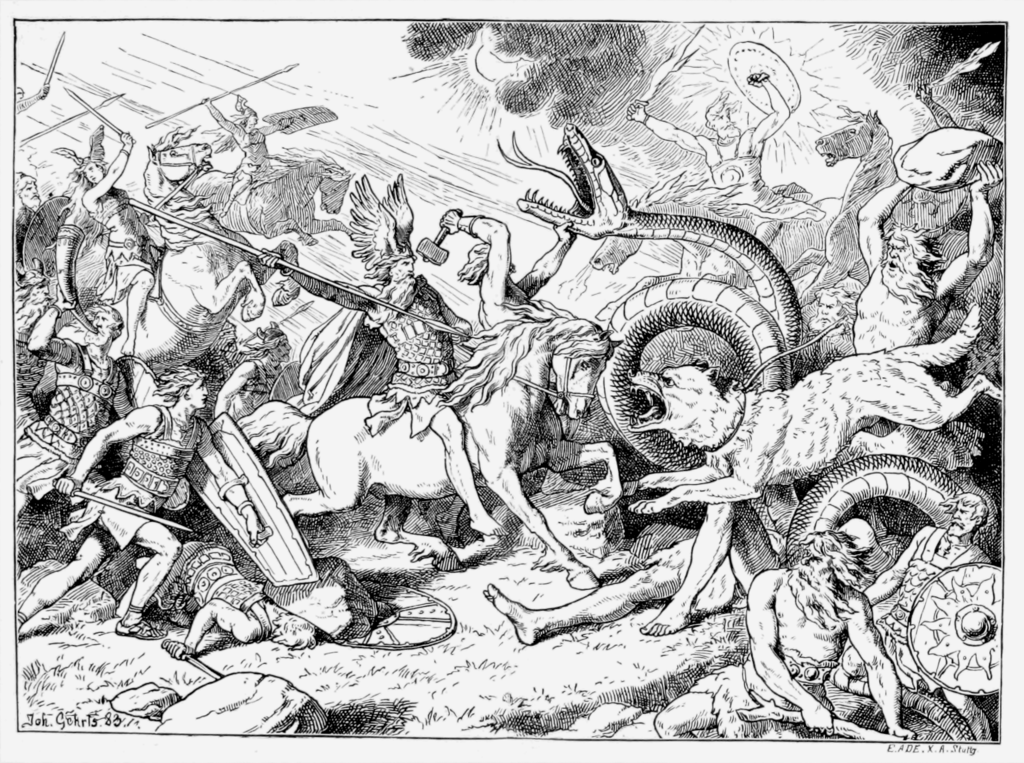

Norse Mythology: Jörmungandr and World Cycles

In Norse mythology, the cosmic serpent Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, encircles the entire world, grasping its own tail much like the Ouroboros. This world-encompassing serpent plays a crucial role in the Norse concept of Ragnarök – the end and subsequent rebirth of the world. During Ragnarök, Jörmungandr is prophesied to release its tail and rise from the ocean, poisoning the sky and battling with the god Thor, with both ultimately perishing in the conflict. After this cosmic destruction, the mythology foretells a renewed world rising from the waters, greener and more fertile than before. The serpent thus serves as both destroyer and enabler of cosmic rebirth, marking the transition between world-ages. Additionally, the Norse god Odin’s ability to transform into a serpent connects snake imagery to shamanic practices of spiritual death and rebirth through shape-shifting. The cyclical nature of Norse cosmology, with its serpentine timekeeper, reflects a universal understanding of destruction as a necessary component of renewal.

African Traditional Religions: Rainbow Serpents and Ancestral Connections

Across various African traditional religious systems, serpents frequently represent continuity between the living and ancestral realms, embodying concepts of rebirth through reincarnation and ancestral presence. The Dahomey religion features Aido-Hwedo, a cosmic rainbow serpent who assisted in creation and now sustains the world by holding it in its coils. In Yoruba tradition, the serpent deity Oshumare appears as a rainbow, connecting heaven and earth and symbolizing the cyclical movement between worlds. Many African cultures associate pythons and other large snakes with ancestral spirits returning in animal form, creating a direct connection between serpents and the concept of rebirth through reincarnation. Vodun and related traditions often keep sacred pythons in shrines, believing these serpents embody ancestral wisdom and provide a physical connection to the spiritual realm. The serpent’s connection to both water (source of life) and the underworld (realm of ancestors) makes it a perfect symbol for the African understanding of life as a continuous cycle of death, ancestral existence, and rebirth.

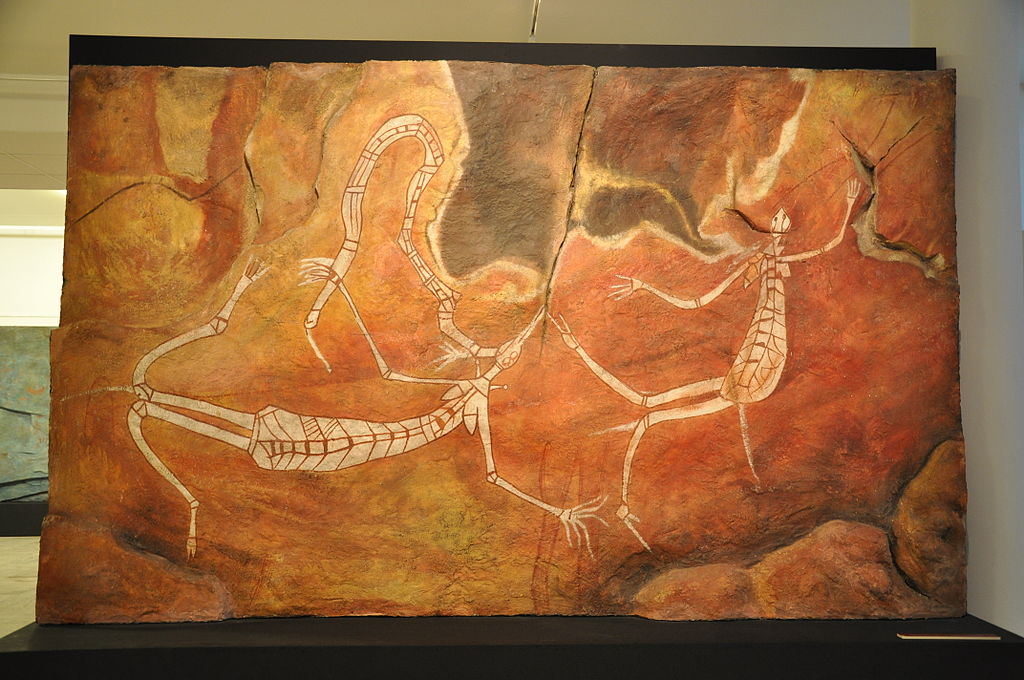

Aboriginal Australian Dreamtime: The Rainbow Serpent

In Aboriginal Australian spiritual traditions, the Rainbow Serpent stands as one of the most significant creator beings, directly connected to concepts of creation, destruction, and rebirth. This immense serpent deity is believed to have shaped the landscape during the Dreamtime, creating mountains, rivers, and waterholes as it moved across the formless earth. The Rainbow Serpent controls the life-giving water that enables regeneration in Australia’s harsh climate, appearing after rains in the form of rainbows. Many Aboriginal groups associate the shedding of snake skin with their own initiation ceremonies, viewing both as processes of transformation and rebirth into new spiritual understanding. The Rainbow Serpent’s cyclical appearances and disappearances mirror the dry and wet seasons, representing the perpetual cycle of dormancy and renewal in nature. As both a nurturing creator and potentially destructive force when angered, the Rainbow Serpent embodies the dual nature of rebirth, which requires destruction before recreation can occur.

Chinese and East Asian Traditions: Dragons and Cosmic Energy

In Chinese and East Asian spiritual traditions, dragons – evolved from serpent imagery – represent cosmic power, transformation, and renewal through their association with water and changing seasons. The Chinese dragon, unlike Western counterparts, brings beneficent rain and symbolizes imperial power and cosmic harmony. During traditional New Year celebrations, dragon dances celebrate renewal and rebirth of the annual cycle, with the serpentine movement of dragon processions embodying flowing life energy. In Taoist alchemy, the inner cultivation of chi energy is often described using serpent and dragon imagery, with the practitioner seeking spiritual rebirth through the circulation of vital energy. Chinese mythology also features stories of carp transforming into dragons after swimming upstream, providing a direct metaphor for spiritual transformation and rebirth through persistent effort. The dragon-serpent’s association with water – the element of change, flow, and regeneration – further strengthens its connection to rebirth concepts throughout East Asian religious and philosophical traditions.

Greek and Roman Traditions: Asclepius and Healing Transformation

In Greco-Roman religious traditions, snakes became powerful symbols of healing, transformation, and renewal through their association with the god Asclepius, deity of medicine and healing. The Rod of Asclepius, a staff entwined by a single serpent, remains a symbol of medicine to this day, representing the god’s healing powers. Patients seeking healing would sleep in Asclepius’ temples where non-venomous snakes would crawl freely, their touch believed to restore health and vitality. The healing sanctuaries called Asclepieia featured sacred serpent pits, and the shedding of snake skin was explicitly connected to recovery from illness – a form of physical rebirth. The Greco-Roman mystery religions, particularly those of Dionysus and Orpheus, also employed serpent imagery in their initiation rites, symbolizing the spiritual death and rebirth of initiates. Even the Gorgon Medusa’s snake-covered head, when used on Athena’s shield, could both petrify enemies and restore life, demonstrating the dual nature of serpent power as both destroyer and regenerator.

Gnostic and Esoteric Traditions: The Serpent of Wisdom

Within Gnostic and esoteric traditions that emerged in the late ancient world, the serpent underwent a radical reinterpretation, becoming a symbol of divine wisdom that enables spiritual rebirth. Contrary to orthodox interpretations, many Gnostic texts portrayed the Eden serpent as an emissary of divine wisdom who awakened humans to their true spiritual nature, initiating their journey toward spiritual rebirth. The Gnostic symbol of the Ouroboros represented self-reflection and the cyclical nature of spiritual enlightenment – an endless process of death and rebirth of consciousness. Medieval alchemical traditions continued this symbolism, using serpent imagery to represent the transformative processes that turned base matter into spiritual gold. The caduceus, with its intertwined serpents, became an emblem of balanced opposing forces and transformative wisdom in Hermetic traditions. These esoteric interpretations viewed the serpent not as a tempter but as an initiator of spiritual transformation, offering the knowledge necessary for soul rebirth and the transcendence of material limitations.

Modern Psychological Interpretations: Jung and Collective Symbolism

Modern psychological interpretations, particularly those of Carl Jung and his followers, have identified the snake as an archetypal symbol of transformation and rebirth embedded in the human collective unconscious. Jung recognized the remarkable consistency of serpent symbolism across cultures as evidence of shared psychological structures that process transformation through similar symbolic language. In Jungian psychology, the snake often represents the unconscious itself – something powerful, potentially dangerous, but ultimately necessary for psychological growth and rebirth. The snake’s ability to shed its skin provides a perfect metaphor for the psychological process of releasing old patterns and emerging with a renewed consciousness. Contemporary depth psychology views engagement with serpent imagery in dreams and art as potentially transformative encounters with the renewal aspects of the psyche. The widespread fear of snakes (ophidiophobia) is interpreted not merely as fear of physical harm but as anxiety about the profound transformation that serpent energy represents – the necessary psychological death that precedes rebirth of consciousness.

Universal Patterns: Why Snakes Became Global Symbols of Rebirth

The remarkably consistent association between snakes and rebirth across disparate cultures reveals several universal patterns in human symbolic thinking. First, the observable biological feature of skin shedding provided a visible, natural metaphor for renewal that was readily available to all human societies regardless of geographic location. Second, the snake’s close association with both earth (through burrowing) and water (many species are excellent swimmers) connected it to primordial elements universally recognized as sources of life and regeneration. Third, the snake’s seemingly paradoxical characteristics – its potentially deadly venom alongside its healing associations, its phallic shape suggesting fertility alongside its chthonic nature suggesting death – made it a perfect emblem for the paradoxical nature of rebirth itself, which requires ending before beginning. Fourth, the snake’s limbless form and sinuous movement created a natural visual representation of cycles and waves, reflecting the cyclical rather than linear understanding of time prevalent in most ancient religious systems. These convergent factors explain why, across continents and millennia, human religious imagination consistently turned to the serpent when conceptualizing the mysteries of death and rebirth.

The serpent’s powerful connection to concepts of rebirth across world religions demonstrates how deeply humans have observed and internalized natural processes as metaphors for spiritual truths. From the biological reality of skin shedding to complex theological systems of cosmic renewal, the snake has maintained its position as perhaps the most universal symbol of transformation and regeneration. This cross-cultural convergence suggests something profound about both human symbolic thinking and our ancestral recognition of patterns in nature. While modern perspectives may have moved away from literal interpretations of serpent deities, the psychological power of the snake as a symbol of renewal remains embedded in art, literature, and spiritual traditions worldwide. As we continue to face personal and collective challenges requiring transformation, the ancient wisdom embodied in serpent symbolism – that renewal requires shedding the old to embrace the new – remains as relevant as ever to the human experience.