Throughout human history, serpents have slithered their way into our mythologies, religions, and cultural beliefs, often embodying both creative and destructive forces. Among these serpentine deities, female snake goddesses hold particularly fascinating positions in various ancient pantheons. These powerful feminine divinities represented fertility, rebirth, wisdom, and healing across diverse civilizations spanning continents and millennia. From the snake-handling priestesses of Minoan Crete to the fearsome Aztec mother of serpents, these goddesses reflect humanity’s complex relationship with snakes—creatures both feared and revered. This exploration takes us through the rich tapestry of snake goddess worship across ancient cultures, revealing surprising connections and unique expressions of divine feminine power.

The Minoan Snake Goddess: Priestess of Crete

Perhaps the most visually iconic snake goddess comes from the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete, dating back to approximately 1600 BCE. Archaeological excavations at Knossos in the early 20th century unearthed remarkable statuettes depicting women holding snakes in their outstretched hands, their elaborate dresses revealing bare breasts. These figurines, made of faience (glazed ceramic), show women with snakes coiling around their arms and sometimes atop their heads, suggesting both control over and communion with these powerful animals. While scholars debate whether these represent an actual goddess or her priestesses, they clearly demonstrate the sacred relationship between women and serpents in Minoan religious practice. The snake’s ability to shed its skin may have symbolized regeneration and immortality to the Minoans, connecting these female figures to life-giving and transformative powers.

Wadjet: The Cobra Goddess of Ancient Egypt

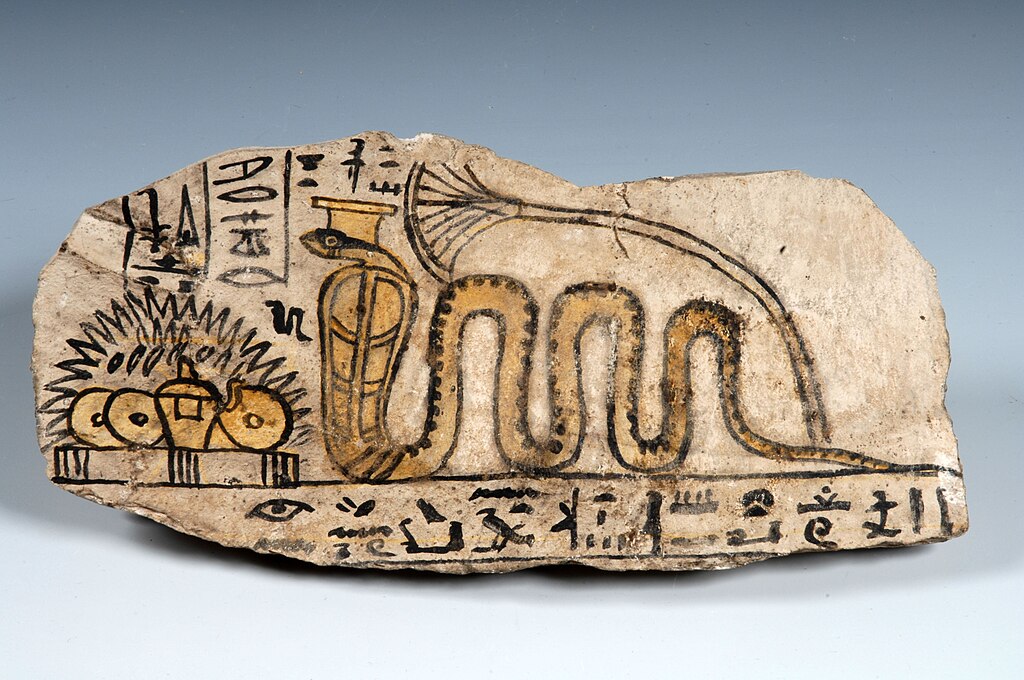

In ancient Egypt, the cobra goddess Wadjet (also spelled Wadjyt or Uto) served as one of the earliest and most important deities in the pantheon. As the protective goddess of Lower Egypt, she was depicted as a rearing cobra and became part of the royal insignia, adorning the pharaoh’s crown as the uraeus—a symbol of divine authority and protection. Wadjet’s fierce protective nature made her a guardian of kings and a defender against enemies. Her cult center was at Per-Wadjet (Greek: Buto), where she was worshipped for over three thousand years. Mythology paired her with Nekhbet, the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt, together symbolizing the unified kingdom as “The Two Ladies,” one of the royal titles in ancient Egyptian protocol. Wadjet’s serpent form represented not only protection but also the fierce heat of the sun and its life-giving power.

Renenutet: Egypt’s Goddess of Nourishment and Harvest

Another powerful serpent goddess from ancient Egypt was Renenutet (also called Ernutet or Thermuthis in Greek), who presided over the harvest and nourishment. Often depicted as a woman with a cobra head or as a complete cobra, Renenutet blessed the fields and protected the grain from pests and vermin. Her name connects to the concept of “rearing” or “nursing,” and she was considered a divine nurse who provided sustenance and protection to the pharaoh and all Egyptians. During harvest time, farmers made offerings to Renenutet, hoping for her blessing on their crops. Her protective nature extended to newborn children, and many Egyptians wore amulets bearing her image for good fortune. Interestingly, Renenutet later became associated with destiny and fate, showing how the serpent goddess’s influence expanded from physical nourishment to spiritual guidance.

Meretseger: The Cobra Goddess of the Theban Necropolis

The peak overlooking the Valley of the Kings in ancient Egypt had a distinctive pyramid shape that inspired the worship of Meretseger, whose name means “she who loves silence.” This cobra goddess was the local deity of the Theban Necropolis, watching over the tombs and their workers. Unlike more universal deities, Meretseger was specifically associated with this sacred burial ground and was believed to punish anyone who desecrated the tombs or committed crimes in her domain. Numerous stelae left by workers from Deir el-Medina show her as a woman with a cobra head or simply as a serpent, sometimes combined with a woman’s head. These monuments often record prayers for forgiveness from those who believed the goddess had punished them with illness or misfortune for their misdeeds. Meretseger was unique among snake goddesses for her localized power and her direct role in maintaining moral order through punishment and forgiveness.

Coatlicue: The Aztec Mother of Serpents

In Mesoamerica, the Aztec civilization venerated Coatlicue, whose name translates to “Serpent Skirt” or “She of the Serpent Skirt.” As a primordial deity, Coatlicue represented both creation and destruction, fertility and death. Her fearsome appearance—depicted wearing a skirt of writhing snakes and a necklace of human hearts and hands—embodied the Aztec understanding that life and death were inseparably intertwined. According to Aztec mythology, Coatlicue was the mother of the moon, stars, and Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun. Her famous statue, now in Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology, shows her with a severed head replaced by two facing serpents, clawed hands and feet, and her characteristic skirt of snakes. This powerful imagery conveyed her role as the earth itself, consuming the dead and giving birth to new life in an endless cycle, with serpents representing this regenerative power.

Manasa: The Snake Goddess of Hindu Tradition

In the Hindu traditions of Eastern India and Bangladesh, Manasa Devi reigns as the goddess of snakes and protection against snakebite. Often depicted as a beautiful woman covered with serpents or sitting on a lotus and sheltered by the hood of a cobra, Manasa represents both danger and healing. According to folklore, she is the sister or daughter of the snake god Vasuki and possesses extensive knowledge of herbs and antidotes. Rural communities especially venerate Manasa during the monsoon season when snakes are most active, offering milk and flowers at her shrines to seek protection from serpent encounters. The worship of Manasa demonstrates how snake goddesses often bridged the gap between folk religion and established pantheons, serving the practical needs of ordinary people concerned with the very real dangers of venomous snakes. Her cult remains vibrant today, particularly in regions where human-snake encounters are common, showing the enduring power of this divine feminine protector.

Lamia: Greece’s Child-Devouring Serpent Woman

Not all snake goddesses were beneficent, as demonstrated by the Greek mythological figure Lamia. Originally a beautiful queen of Libya, Lamia became the lover of Zeus, incurring the wrath of his wife Hera. In her jealousy, Hera killed Lamia’s children, driving her mad with grief and transforming her into a serpent-like monster who hunted and devoured the children of others. Different versions of the myth describe Lamia with a serpent’s tail instead of legs, the ability to remove her eyes, and an insatiable hunger for human flesh. By the classical period, “lamia” became a general term for female child-stealing demons or vampiric entities, reflecting deep-seated fears about infant mortality in the ancient world. The figure of Lamia demonstrates how snake goddesses could embody cultural anxieties, particularly those surrounding motherhood, female sexuality, and the vulnerability of children, serving as cautionary figures rather than objects of worship.

Chicomecoatl: Aztec Goddess of Maize and Nourishment

The Aztec pantheon included another important snake goddess, Chicomecoatl, whose name means “Seven Serpent” in Nahuatl. As the goddess of maize, agriculture, and sustenance, she embodied the life-giving properties of corn, the staple crop of Mesoamerican civilizations. Typically depicted as a young woman carrying ears of corn or wearing a distinctive rectangular headdress called an amacalli, Chicomecoatl received offerings during multiple agricultural festivals throughout the year. The number seven in her name held cosmological significance in Aztec numerology, while the serpent component connected her to fertility and the earth. During her festival in the seventh month of the Aztec calendar, a young girl representing the goddess would be sacrificed to ensure bountiful harvests. The worship of Chicomecoatl demonstrates how serpent symbolism in Mesoamerican cultures was deeply tied to agricultural cycles and the nourishment of the community, with female deities often mediating this relationship between humans and the vital crops they depended upon.

The Python Priestess of Delphi

At the sacred site of Delphi in ancient Greece, the Oracle or Pythia served as the human vessel for divine prophecy, connecting her to serpentine powers through the myth of Python. According to Greek tradition, Apollo slew the great serpent Python who guarded the navel of the earth at Delphi, establishing his oracle at this powerful location. The priestess who delivered Apollo’s prophecies took the title Pythia, derived from the slain serpent’s name, and sat on a tripod over a fissure in the earth from which intoxicating vapors were said to rise. These vapors were believed to be the breath of Python or the decomposing body of the great serpent, giving the priestess access to chthonic (underworld) knowledge. While not a goddess herself, the Pythia represents how mortal women could channel serpentine power, acting as intermediaries between divine serpent forces and humanity. Her role demonstrates the enduring association between snakes, prophetic powers, and women in the ancient Mediterranean world.

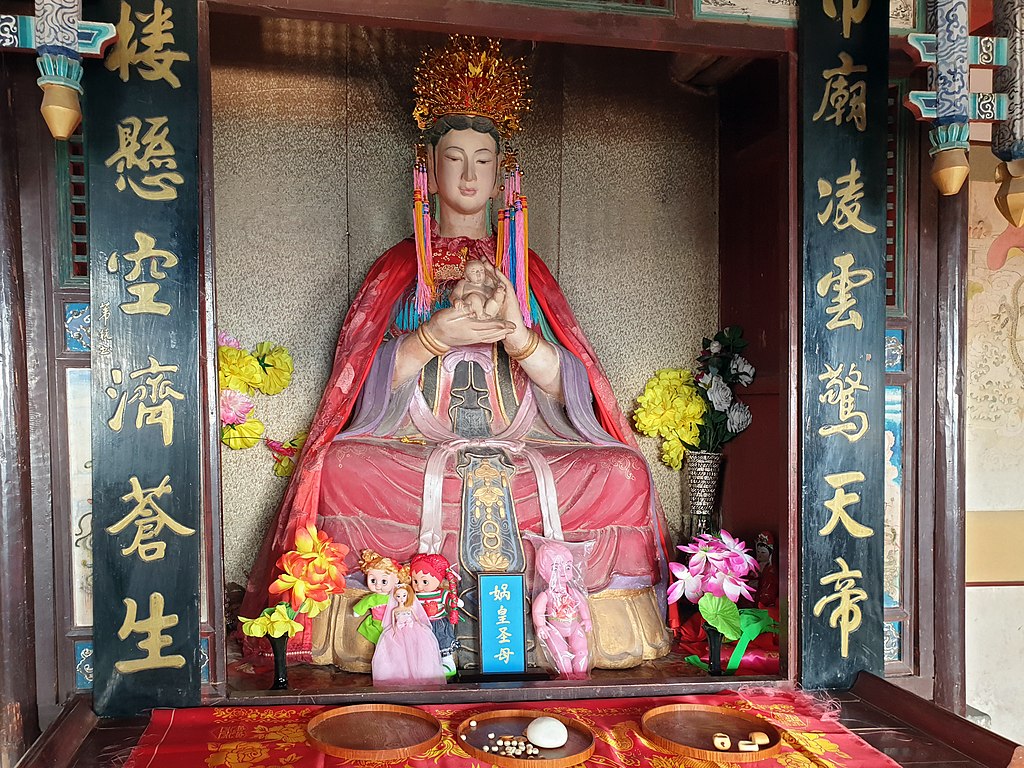

Nüwa: The Snake-Bodied Creator Goddess of Chinese Mythology

In ancient Chinese mythology, Nüwa (also spelled Nü Wa) appears as a primordial goddess with the head of a woman and the body of a serpent or dragon. According to various traditional texts, Nüwa created humanity by sculpting figures from yellow clay, breathing life into them, and teaching them to reproduce. When a great flood threatened creation, she mended the broken pillars of heaven with five-colored stones, saving the world from destruction. As one of the earliest feminine deities in Chinese myth, Nüwa represents creative power, nurturing protection, and cosmic order. Traditional depictions show her intertwined with her brother/consort Fuxi, who also has a serpentine lower body, their tails forming a double helix pattern that some scholars interpret as an ancient understanding of natural complementary forces. The serpent form connects Nüwa to the earth and water, emphasizing her chthonic nature and life-giving powers that sprung from the primordial waters of creation.

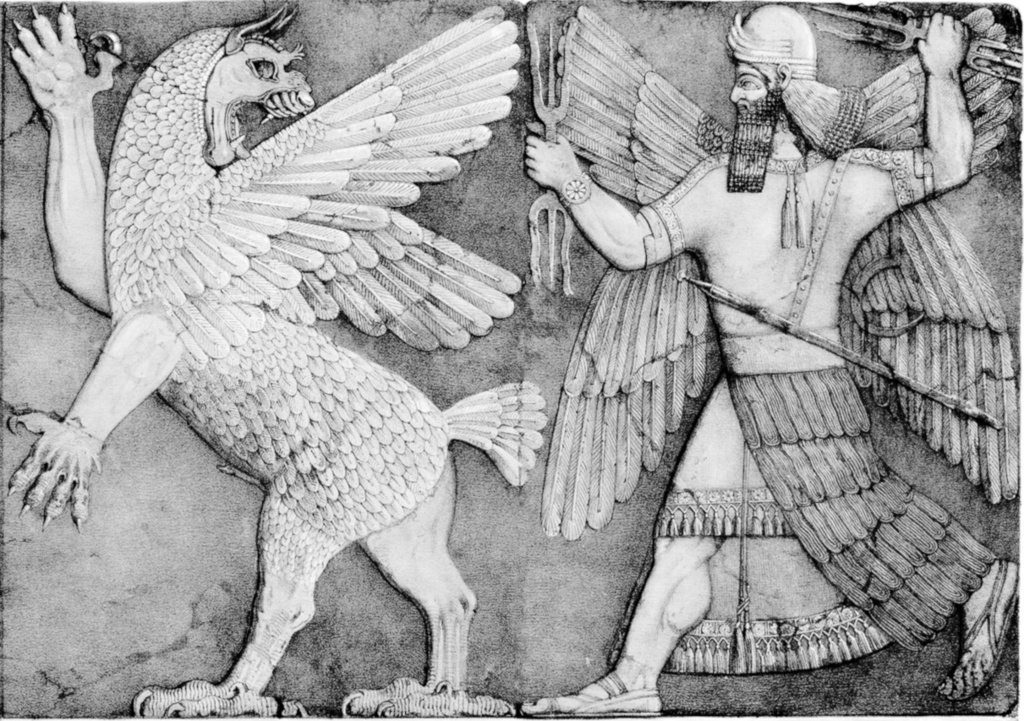

Tiamat: Mesopotamia’s Primordial Serpent Mother

In the ancient Mesopotamian creation epic Enuma Elish, Tiamat emerges as the primordial goddess of salt water, often conceptualized as a vast serpentine or dragon-like being. As the mother of the first generation of gods, Tiamat initially represents creative chaos and the untamed waters from which all life emerged. The epic describes how, following a divine conflict, she creates eleven monstrous creatures to battle against the younger gods, only to be defeated and slain by the storm god Marduk, who uses her body to fashion the cosmos. Though Tiamat’s representation varies across different periods and regions of Mesopotamia, her serpentine aspects connect her to other Near Eastern serpent deities and primordial water beings. Her dual nature as both creator and destroyer, nurturing mother and vengeful monster, exemplifies the complex and often ambivalent view of snake goddesses in ancient consciousness. Tiamat’s story reveals how serpent goddesses often embodied primordial forces that predated more orderly pantheons, representing both the creative potential and destructive power of the natural world.

Nagini: The Female Serpent Deities of South Asian Traditions

Throughout the Indian subcontinent, female naga deities called nagini (or nāginī) have been venerated for thousands of years as powerful supernatural beings associated with water, fertility, and wisdom. These serpent goddesses, capable of assuming either fully serpentine or half-human forms, guard hidden treasures and secret knowledge, particularly related to medicine and healing arts. In Buddhist and Hindu iconography, nagini are often depicted as beautiful women from the waist up with serpent bodies below, sometimes shown with multiple cobra hoods. Sacred sites dedicated to nagini can be found near water sources, reflecting their association with life-giving waters and rainfall. In regions like Kerala, local nagini worship continues to this day at snake shrines called sarpa kavu, where offerings are made to prevent infertility, skin diseases, and other conditions believed to result from serpent curses. These graceful yet powerful beings straddle the line between goddess and spirit, demonstrating how serpent veneration takes diverse forms across cultural landscapes.

The Legacy and Endurance of Snake Goddess Worship

The worship of snake goddesses has persisted across cultures and centuries, evolving rather than disappearing completely. In contemporary Hinduism, the goddess Manasa continues to receive offerings, while modern Paganism and Goddess-centered spirituality have revived interest in figures like the Minoan Snake Goddess. The psychological power of these serpentine female deities remains evident in their recurrence in modern literature, art, and popular culture, from fantasy novels to video games. Scholars of religion and psychology, including Carl Jung, have suggested that snake goddesses represent fundamental archetypes in human consciousness—embodying transformation, intuitive wisdom, and the feminine connection to earth energies. Even in regions where formal worship has ceased, snake goddesses have left their imprint on folklore, superstitions, and cultural practices surrounding snakes. The powerful symbols of the divine feminine entwined with serpents continue to resonate, perhaps because they address enduring human concerns about life, death, and regeneration—the eternal cycle represented by the ouroboros, the snake that swallows its own tail.

The ancient snake goddesses, spanning diverse civilizations from Minoan Crete to Aztec Mexico and from Egypt to China, reveal humanity’s complex relationship with serpents as symbols of both life and death. These powerful feminine deities transcended simplistic categorization, embodying creation and destruction, healing and harm, wisdom and danger. Their worship addressed fundamental human needs—protection from venomous bites, agricultural fertility, prophetic guidance, and understanding of life’s cyclical nature. While specific cults have faded, the psychological impact of these goddesses endures in cultural memory and artistic expression. The serpent, with its ability to shed its skin and renew itself, paired with feminine creative power, continues to represent transformation and rebirth. These ancient goddess figures remind us that across vastly different cultures, humans found similar symbolic language to express their relationship with nature’s most mysterious powers, embodied in the sinuous form of the divine serpent woman.