When we encounter snakes in the wild or as pets, we often misinterpret their behaviors through a human lens. What might look threatening or aggressive to us is frequently something entirely different from the snake’s perspective. Snakes, despite their reputation, rarely display true aggression without cause. Instead, what we perceive as aggression is typically defensive behavior, natural exploration, or biological necessities. Understanding these behaviors not only helps us better appreciate these fascinating reptiles but also promotes safer interactions with them. Let’s explore nine commonly misunderstood snake behaviors that are frequently mislabeled as aggression.

Defensive Striking Versus Aggression

When a snake strikes with its mouth open, many people immediately label this as an aggressive attack, but there’s an important distinction to make. Defensive striking is a snake’s way of saying “please back away” rather than “I want to hurt you.” You can identify defensive strikes by their accompanying behaviors—the snake typically recoils quickly after striking, doesn’t pursue its target, and often strikes with closed mouth or minimal fang extension. Truly aggressive strikes, which are rare, involve the snake advancing toward the perceived threat rather than maintaining or creating distance. Understanding this difference can help reduce unnecessary fear and harm to these animals who are simply trying to protect themselves from what they perceive as a much larger predator.

Tongue Flicking as Sensory Exploration

A rapidly flicking tongue often appears threatening to humans, but this behavior has nothing to do with aggression or preparation to strike. Snakes rely heavily on their forked tongues to collect chemical particles from the air, which they then analyze using their vomeronasal organ (Jacobson’s organ) located in the roof of their mouth. This chemical sensing system is how snakes “smell” their environment, detect prey, identify potential mates, and navigate their surroundings. The speed of tongue flicking typically increases when a snake is more actively investigating something interesting or unfamiliar, similar to how humans might look more closely at something that catches our attention. Far from being aggressive, a flicking tongue indicates a curious snake that’s simply trying to understand its environment better.

Head Raising and Neck Flattening

When a snake raises its head and flattens its neck, many people assume it’s preparing to attack, but this is actually a classic defensive posture. Species like cobras are famous for this behavior, but many non-venomous snakes like rat snakes and garter snakes also flatten their necks and raise their heads when feeling threatened. This posture serves to make the snake appear larger and more intimidating to potential predators—essentially, it’s the reptile equivalent of puffing out your chest to look bigger. The snake is broadcasting “I’m dangerous, don’t mess with me” as a bluff to avoid conflict rather than seeking to initiate one. Once the perceived threat moves away, the snake will typically try to escape rather than pursue, confirming the defensive rather than aggressive nature of this display.

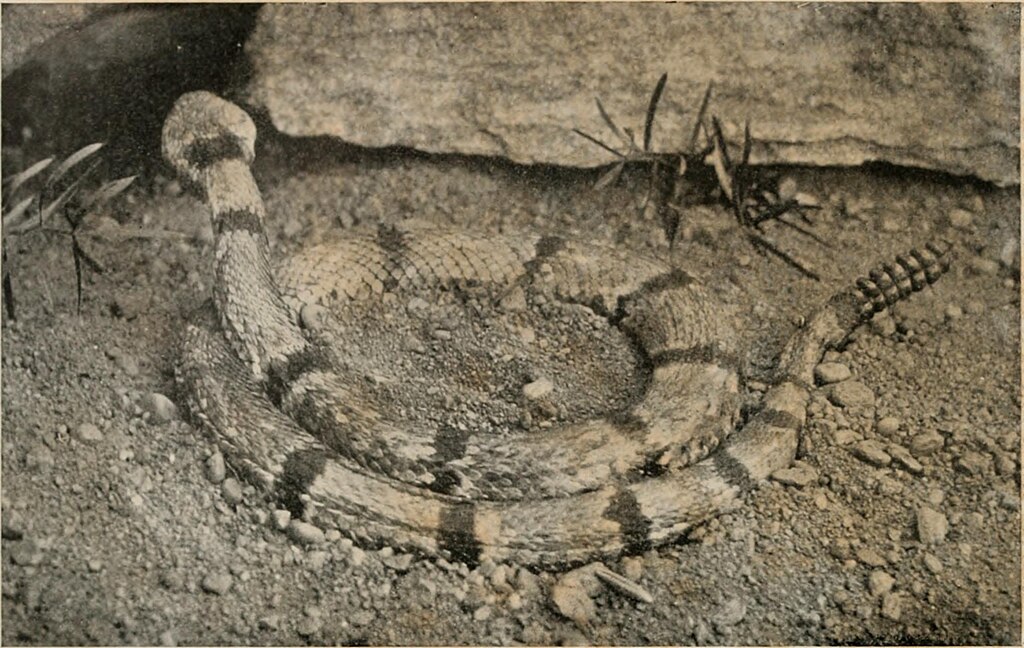

Tail Rattling and Vibration

While rattlesnakes are well-known for their warning behavior, many non-venomous snakes also vibrate or rapidly shake their tails when feeling threatened—often creating a buzzing sound against dry leaves or grass. This behavior is frequently misinterpreted as aggressive intent when it’s actually a sophisticated warning system designed to prevent conflict. By creating noise and drawing attention to their tail end, snakes are effectively saying “I see you, please leave me alone,” and giving potential threats an opportunity to retreat before closer interaction becomes necessary. Many rat snakes, bull snakes, and even some kingsnakes exhibit this behavior, despite having no rattle. This fascinating example of convergent evolution shows how effective this warning mechanism is as a non-aggressive form of self-protection across different snake species.

Hissing as a Warning Signal

The intimidating hiss of a snake is one of nature’s most effective warning signals, but it’s frequently misunderstood as a sign of imminent attack. In reality, hissing is a defensive vocalization designed to communicate “back away” to potential threats without resorting to physical confrontation. When a snake hisses, it’s actually expelling air forcefully through a specialized structure in its glottis called the glottal fissure, creating the distinctive sound that makes predators think twice. Species like bull snakes and pine snakes have particularly loud, impressive hisses that can mimic the warning sound of a rattlesnake. A hissing snake is essentially using its version of a home security system—making noise to scare away intruders rather than engaging in actual combat, which would be risky for the snake as well.

Freezing or Remaining Motionless

When a snake suddenly becomes completely still upon detecting your presence, this isn’t a prelude to an attack—it’s actually the opposite. Freezing behavior is a primary defense mechanism where the snake is hoping to avoid detection altogether by blending into its surroundings and minimizing movement that might attract attention. This behavior demonstrates that the snake’s first preference is to remain unnoticed rather than engage in any kind of confrontation. Many species rely on their incredible camouflage as their main protection, and remaining motionless maximizes the effectiveness of this natural defense. If you encounter a frozen snake, it’s experiencing fear rather than preparing to be aggressive, and giving it space will allow it to eventually continue on its way once it feels the threat has passed.

False Striking or Strike Feinting

Some snakes perform what appears to be a strike but with no intention of making contact—a behavior known as strike feinting or false striking. During this display, the snake may lunge forward with a closed mouth or deliberately fall short of its target. This behavior is purely meant to scare away a perceived threat without risking actual physical confrontation that could potentially harm the snake. Species like hognose snakes are particularly known for their dramatic false strikes that can be quite convincing to predators and humans alike. When a snake performs this bluffing behavior, it’s essentially the reptilian equivalent of a person shouting “boo!” to scare someone away—startling but ultimately harmless. Understanding this helps us recognize that the snake is actually showing restraint rather than aggression.

Rapid Movement and Retreat

When a snake moves quickly in your presence, it’s natural to interpret this as a charge or aggressive approach, but rapid movement is almost always an escape attempt rather than an attack. Snakes are generally shy creatures that view humans as potential predators due to our size advantage. Their first instinct when encountering larger animals is to escape to safety as quickly as possible. If a snake appears to be moving toward you, it’s likely coincidental—the snake is probably trying to reach a nearby hiding spot that happens to be in your direction. Even species with reputations for standing their ground, like cottonmouths, will typically choose flight over fight when given enough space and warning. Respecting this need for escape by stepping back and creating distance is the best response when encountering a snake on the move.

Playing Dead or Death-Feigning

Perhaps one of the most misunderstood snake behaviors is thanatosis, commonly known as playing dead or death-feigning. Some species, most famously the eastern hognose snake, will roll onto their backs, open their mouths, extend their tongues, and even emit a foul-smelling musk to convince predators they’re already dead and therefore not worth eating. This elaborate performance might seem bizarre to human observers and is sometimes incorrectly interpreted as the snake being ill, aggressive, or dangerous in some way. In reality, this is a last-ditch defensive strategy used when all other warning systems have failed to deter a persistent threat. The behavior demonstrates just how far snakes will go to avoid actual conflict, showcasing their non-aggressive nature even in highly stressful situations.

Regurgitation Under Stress

One particularly misunderstood behavior occurs when a recently-fed snake regurgitates its meal during an encounter with humans. This isn’t an aggressive act but rather an extreme stress response and survival mechanism. When threatened, snakes will sometimes expel recently consumed prey to lighten their body weight for faster escape or to distract a potential predator with the meal. This physiological response is extremely taxing on the snake’s system and can lead to health complications if it happens frequently. For pet snake owners, this behavior is a clear sign that handling should be avoided after feeding (typically for 48-72 hours), as the snake perceives being picked up as a predatory threat. Understanding that regurgitation is a stress response rather than aggression helps both wild snake encounters and captive care practices become more respectful of these animals’ biological needs.

Body Puffing and Inhaling

When a snake suddenly inflates its body by taking in a large amount of air, many people mistake this for aggressive posturing when it’s actually a defensive bluff. By expanding their bodies, snakes create the illusion of being larger and potentially more dangerous than they actually are. Snake species from the common garter snake to the intimidating eastern indigo make use of this tactic when they feel cornered or threatened. Some species combine this inflation with flattening their bodies vertically or horizontally to maximize their apparent size from the perspective of a potential predator. This behavior is comparable to a cat arching its back and puffing up its fur when threatened—a way of saying “don’t mess with me” that helps avoid actual physical confrontation, which could be dangerous for both parties involved.

Understanding Snake Body Language for Safer Interactions

Learning to accurately interpret snake body language can dramatically improve both human safety and snake welfare during encounters. By recognizing the early warning signs of stress in snakes—such as rapid breathing, tense muscles, or defensive positioning—we can adjust our behavior before the snake feels compelled to escalate to more dramatic defensive displays. For wild encounters, maintaining a respectful distance of at least 6 feet from any snake is generally sufficient to prevent triggering defensive responses. When working with captive snakes, understanding subtle cues like head positioning, muscle tension, and breathing rate can help handlers determine when a snake is comfortable versus when it needs space. Like all animals, snakes communicate constantly through their body language, and learning their “language” is key to recognizing that what we often perceive as aggression is actually communication designed to avoid conflict.

Conclusion

Understanding snake behavior requires us to set aside our mammalian biases and appreciate these animals on their own terms. What we often misinterpret as aggression is actually a sophisticated system of warnings, bluffs, and defensive mechanisms designed to prevent conflict whenever possible. Snakes typically want nothing more than to be left alone to pursue their ecological roles without human interference. By learning to recognize these nine commonly misunderstood behaviors, we can develop more respectful relationships with these remarkable reptiles, reduce unnecessary fears, and promote more effective conservation efforts. Whether you’re a casual nature enthusiast or a dedicated herpetologist, seeing past the myth of the “aggressive snake” opens the door to appreciating the true complexity and beauty of these ancient, remarkably adapted animals.