Serpent worship, or ophiolatry, represents one of the most widespread and enduring religious phenomena in human history. Across continents and millennia, snakes have slithered their way into the religious iconography, mythology, and rituals of numerous ancient civilizations. These fascinating reptiles—simultaneously feared and revered—embodied powerful dualities: life and death, healing and harm, wisdom and temptation. Their ability to shed their skin symbolized rebirth and transformation, while their deadly venom represented both destruction and medicinal potential. From the jungles of Mesoamerica to the banks of the Nile, from Mediterranean islands to the Indian subcontinent, diverse cultures independently developed complex religious systems where serpents played central roles as deities, divine messengers, or manifestations of cosmic forces. This exploration takes us through seven remarkable ancient civilizations where snake worship not only existed but thrived as a cornerstone of religious and cultural identity.

Ancient Egypt: The Protective Uraeus

In ancient Egypt, the cobra goddess Wadjet emerged as one of the earliest and most significant serpent deities, serving as the protective goddess of Lower Egypt. Her image—the uraeus—adorned the foreheads of pharaohs as a royal emblem, believed to spit fire at enemies and symbolize the ruler’s divine authority and connection to the gods. Another prominent serpent figure was Apophis (or Apep), the enormous chaos serpent who represented the forces of dissolution and darkness, eternally battling with the sun god Ra during his nightly journey through the underworld. The Egyptian relationship with serpents exemplified their dualistic worldview: while some snakes were venerated as protectors, others represented chaos that must be overcome. In Egyptian healing practices, snake imagery appeared frequently in magical texts and medicinal formulas, reflecting their association with both poison and its antidote.

Mesoamerican Civilizations: Quetzalcoatl and the Feathered Serpent

Among the most visually striking serpent deities in world mythology, Quetzalcoatl—the “Feathered Serpent”—dominated Mesoamerican religious traditions for nearly two millennia. First appearing in Olmec iconography around 1400 BCE, this deity reached its zenith of importance among the later Aztecs, who considered Quetzalcoatl a creator god associated with wind, learning, and civilization. In Maya culture, a similar deity named Kukulkan featured prominently in religious practices, architectural design, and calendrical systems. The massive pyramid at Chichen Itza demonstrates the sophisticated astronomical knowledge of the Maya, as it was constructed so that during equinoxes, sunlight creates the illusion of a serpent descending the pyramid’s steps. Archaeological evidence reveals that serpent motifs adorned temples, palace walls, and ceremonial objects throughout Mesoamerica, and live serpents were likely used in rituals including blood sacrifices to ensure agricultural fertility.

Ancient Greece: Serpents of Healing and Prophecy

The Greeks maintained a complex relationship with serpents, incorporating them into multiple aspects of their religious and medicinal practices. Most famously, Asclepius, the god of medicine and healing, carried a staff entwined with a single serpent—a symbol that continues to represent medicine today. His temples, called Asclepeions, served as healing centers where non-venomous snakes crawled freely, sometimes slithering over sick supplicants as part of the therapeutic process. At Delphi, the most important oracle in the ancient world, the Pythia (priestess) communed with Apollo at a site believed to have been originally sacred to Python, the great serpent slain by Apollo. Greek mythology teems with serpentine figures, including the Gorgons with their snake-hair, the water-dwelling Hydra, and various chthonic (underworld) deities associated with serpents. Many of these associations stemmed from the snake’s connection to the earth and underworld, as they emerge from holes in the ground and shed their skin in a symbolic rebirth.

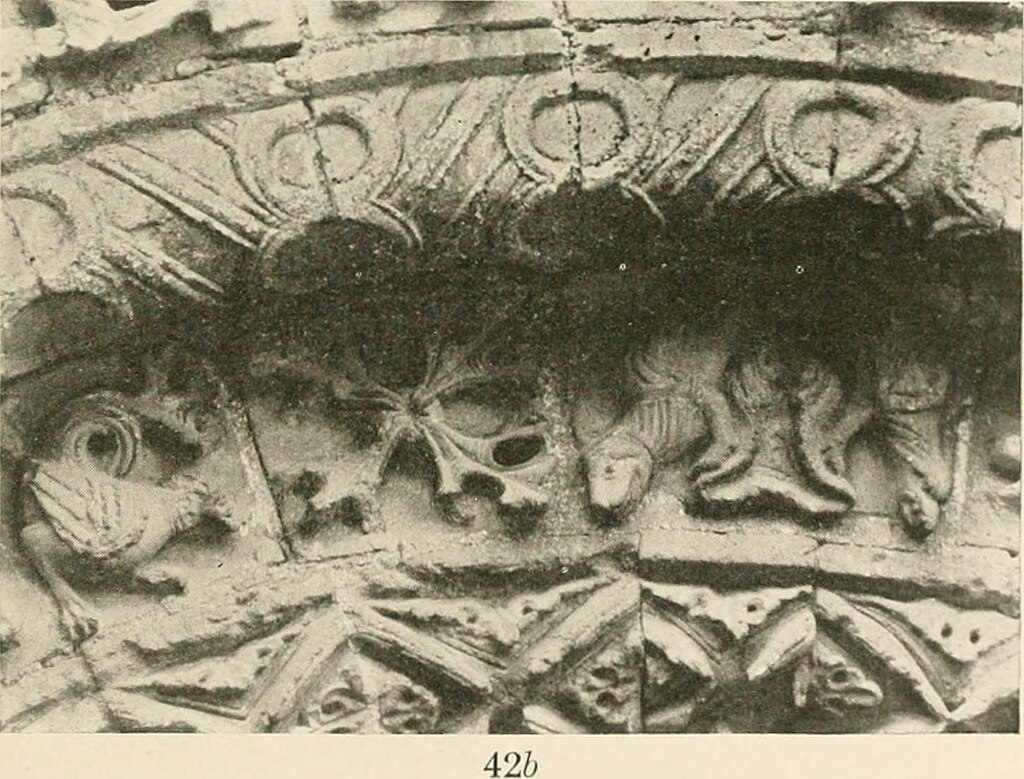

Minoan Crete: The Snake Goddess

The enigmatic civilization of Bronze Age Crete produced some of the most striking serpent imagery in Mediterranean archaeology, particularly the famous “Snake Goddess” figurines excavated at the palace of Knossos. These faience statuettes, dating to approximately 1600 BCE, depict female figures holding serpents in outstretched hands, their elaborate costumes suggesting religious or royal significance. The exact meaning of these artifacts remains debated, but most scholars agree they demonstrate the importance of serpent worship in Minoan religious practices. Archaeological evidence suggests that live snakes may have been kept in Minoan households and sacred spaces as manifestations of chthonic deities associated with renewal and household protection. The labyrinthine design of Minoan palaces, with their numerous storage rooms and ceremonial spaces, provided ideal habitats for snakes, potentially strengthening this religious association. Unlike many contemporaneous societies that viewed serpents with ambivalence, Minoan artifacts suggest an overwhelmingly positive association between women, divine power, and serpents.

Ancient India: Nagas and Cosmic Serpents

Few cultures developed as elaborate a serpent mythology as ancient India, where nagas (divine snake beings) featured prominently across Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. The cosmic serpent Shesha (or Ananta) serves as the resting place for Vishnu between cycles of universal creation, while the snake king Vasuki became the rope in the churning of the cosmic ocean. Particularly in southern India, naga stones and shrines dot the landscape even today, where offerings are made to ensure fertility, rain, and protection from snakebites. The festival of Nag Panchami remains an important religious observance where live cobras receive veneration as divine beings. In Buddhist tradition, nagas protected the Buddha during meditation and safeguarded sacred texts until humanity was ready to receive them. Archaeological evidence from Indus Valley Civilization sites suggests serpent worship may extend back to India’s earliest urban settlements, with seal imagery depicting figures surrounded by snakes dating to approximately 2600-1900 BCE.

Norse Mythology: Jörmungandr the World Serpent

In the cold northern reaches of Europe, Norse mythology featured one of the most dramatic serpent figures in world religion: Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent. This monstrous offspring of Loki grew so large it encircled the entire world, grasping its own tail in an endless loop reminiscent of the ouroboros symbol found in many cultures. Unlike the venerated serpents of warmer climates, Jörmungandr represented a destructive cosmic force destined to play a crucial role in Ragnarök, the Norse apocalypse. According to the myth, Thor, the thunder god, would eventually slay the World Serpent during this final battle, only to fall himself after taking nine steps, poisoned by the creature’s venom. Archaeological evidence suggests that serpent imagery appeared on Norse standing stones, ship carvings, and decorative metalwork, though typically in more threatening contexts than the protective serpents of Mediterranean and Eastern religions. Despite its destructive associations, the world-encircling serpent represented important cosmological principles of cyclical time and the boundaries of the known world.

Ancient China: The Divine Dragon

While technically not serpents in the strict zoological sense, Chinese dragons evolved from earlier serpent worship and maintained many snake-like attributes, earning their place in this exploration. Early Chinese serpent deities gradually transformed into the more elaborate dragon figures seen in later dynasties, but retained their associations with water, rainfall, and agriculture. Archaeological evidence from Neolithic Yangshao culture (5000-3000 BCE) reveals pottery decorated with serpentine figures, suggesting an ancient origin for this veneration. By the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), dragon imagery had become firmly established in royal iconography and divination practices. The dragon kings (long wang) controlled rainfall and water bodies, requiring proper veneration to ensure agricultural prosperity and prevent flooding. Unlike Western traditions that often demonized dragons and serpents, Chinese culture overwhelmingly portrayed these beings as benevolent, wise, and deserving of reverence—attitudes that persist in modern Chinese festivals and cultural practices.

The Symbolism of Serpent Worship

Across diverse civilizations, serpents consistently embodied certain symbolic qualities that help explain their religious significance. The snake’s ability to shed its skin made it a powerful symbol of regeneration, immortality, and cyclical time—concepts central to many religious worldviews. Their emergence from the earth and tendency to inhabit underground spaces connected them to chthonic forces, ancestor worship, and agricultural fertility. The deadly venom of certain species created associations with both destruction and, paradoxically, healing (following the ancient principle that poison can be medicine in proper doses). Finally, the serpent’s fluid movement, lacking limbs yet moving with purpose, suggested a primordial form of life—ancient, mysterious, and closer to creative cosmic forces than more “evolved” creatures. These symbolic associations, combined with the genuine awe and fear inspired by encounters with snakes, created perfect conditions for their religious veneration across continents and millennia.

Serpent Temples and Sacred Architecture

Ancient civilizations frequently designed sacred spaces that incorporated serpent imagery or facilitated actual serpent presence in religious rituals. The Temple of Kukulkan at Chichen Itza represents perhaps the most dramatic example, with its shadow-serpent effect during equinoxes and serpentine balustrades flanking the main staircase. In India, specially designed naga temples featured snake pits where live cobras could be kept and venerated by devotees seeking blessings. Greek Asclepeions included abaton (sleeping rooms) where non-venomous snakes could move freely among patients as part of the healing process. Archaeological evidence suggests that in Minoan Crete, certain rooms within palatial complexes contained platforms and vessels potentially used for keeping sacred snakes. These architectural features reflect the importance of creating physical spaces where human worshippers could interact with serpentine deities or their living representatives in controlled ritual contexts.

Serpent Worship Practices and Rituals

The practical aspects of serpent veneration varied widely across cultures but often included specific ritual protocols. In many traditions, milk offerings represented the preferred tribute to serpent deities, perhaps due to the observed tendency of some snakes to drink milk when domesticated. Seasonal festivals marking the emergence of snakes from hibernation occurred in multiple cultures, celebrating the symbolic rebirth of these creatures and, by extension, the renewal of natural cycles. Human-serpent ritual interactions ranged from the handling of non-venomous species to more dangerous demonstrations of faith involving cobras and vipers, particularly in India where snake charmers originally served religious rather than entertainment purposes. Sacrifice of animals (and in some Mesoamerican contexts, humans) to serpent deities formed part of more elaborate ceremonial complexes intended to ensure cosmic balance and agricultural prosperity. Archaeological evidence, including specialized vessels, altars, and offering pits at serpent shrines, provides material confirmation of these practices described in textual sources.

The Legacy of Serpent Worship in Modern Times

Though diminished by modern religious systems and scientific understanding, serpent worship persists in various forms across the contemporary world. The previously mentioned Nag Panchami festival continues in India, where decorated cobras receive offerings from devotees seeking protection and blessings. In parts of Africa and the Caribbean, syncretic religious traditions incorporate serpent deities like Damballa from the Vodou pantheon, believed to manifest during certain possession rituals. The medical caduceus, though technically a misappropriation of the staff of Hermes rather than the rod of Asclepius, perpetuates ancient associations between serpents and healing in modern medical iconography. In parts of Appalachia in the United States, certain Christian sects practice snake handling during religious services, interpreting biblical passages about “taking up serpents” literally. Even secular culture maintains ambivalent fascination with serpents, from snake tattoos to the serpentine imagery in corporate logos, demonstrating the enduring psychological power these creatures exert on human imagination.

Serpents in Creation Myths

Across numerous ancient cultures, serpents featured prominently in creation mythology, often representing primordial chaos preceding ordered existence. In Norse cosmology, Jörmungandr emerged from the primeval void along with other monstrous offspring of Loki, embodying forces that both threatened and defined the boundaries of the created world. Egyptian creation myths featured Apep as the uncreated force of chaos existing before the ordered universe, while other traditions portrayed benevolent creator serpents shaping the world through their movements. Mesoamerican origin stories described how Quetzalcoatl and his divine counterpart Tezcatlipoca tore apart the primordial earth-crocodile to create the world from her body. In Hindu cosmology, the world rests upon the great serpent Shesha, who in turn floats upon the cosmic waters, creating a serpentine foundation for existence itself. These creation narratives reflect an intuitive understanding of serpents as ancient, primordial beings whose mysterious nature and emergence from the earth connected them to the very origins of the world.

Scientific Perspectives on Widespread Serpent Worship

Modern evolutionary psychology and cognitive science offer compelling explanations for the cross-cultural prevalence of serpent worship in ancient civilizations. Research suggests humans may possess an evolved predisposition to detect and respond emotionally to snake stimuli—a trait potentially preserving our ancestors from deadly encounters. This innate “snake detection theory” proposes that primate brains evolved specialized neural pathways for rapid snake recognition, explaining why serpents so readily acquired symbolic significance across unconnected cultures. Anthropologists note that ancient peoples would have observed unique snake behaviors—shedding skin, moving without limbs, striking with deadly precision—that naturally invited metaphysical interpretations. The widespread geographic distribution of snakes across human-inhabited regions (unlike more localized dangerous animals) made them universally available for religious incorporation. Combined with their practical significance as both threats and, paradoxically, sources of venom used in early medicine, these factors created perfect conditions for serpents to slither into religious systems worldwide, representing cosmic dualities that resonated with human experience.

Through this exploration of seven ancient civilizations and their serpent worship traditions, we gain valuable insight into how humans have interpreted and integrated the natural world into religious systems. The serpent—mysterious, dangerous, yet also regenerative—provided ancient cultures with a powerful symbol through which to understand cosmic forces, life cycles, and the dualities of existence. Despite cultural, geographic, and temporal differences, remarkable similarities emerge in how these civilizations incorporated serpents into their worldviews, suggesting something fundamentally compelling about these creatures to the human mind. As we continue to encounter snakes in modern contexts ranging from religious ceremonies to medical symbols, we participate in an unbroken chain of human-serpent relationships stretching back to our earliest ancestors. The enduring legacy of serpent worship reminds us that beneath our modern scientific understanding, ancient symbolic associations continue to shape how we perceive these remarkable creatures and our relationship to the natural world.